drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

line

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

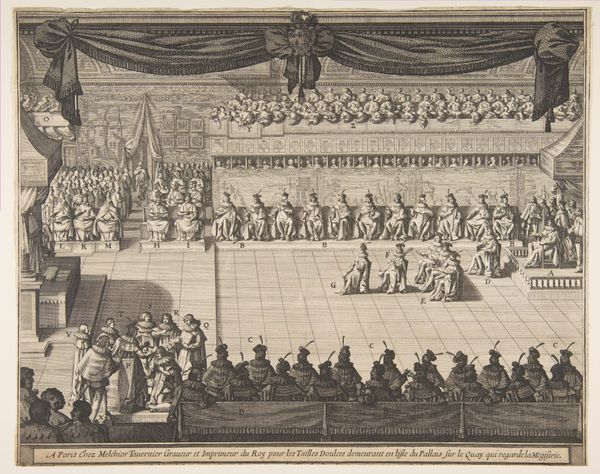

Dimensions: Sheet (trimmed): 10 15/16 × 13 9/16 in. (27.8 × 34.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This etching, created by Abraham Bosse in 1634, depicts the "Banquet of the Chevaliers of the Holy Spirit." It’s currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The detailed lines offer us a glimpse into the social customs and ceremonies of the French aristocracy. Editor: My immediate reaction is of organized opulence. The linear perspective draws the eye deep into the hall, overwhelmed by the sheer number of people and platters meticulously arranged. But the mood is somewhat cold, isn't it? The uniformity mutes the individuals. Curator: Absolutely. Bosse’s prints, especially this one, are valuable because they record specific rituals and fashions of the time. The Order of the Holy Spirit was the highest order of French chivalry, so documenting their ceremonies visually reinforced their social status. Note the architecture. Bosse presents classical architectural backdrops, thus drawing parallels between present day royal court with historic and mythological past. Editor: It's the overwhelming symbolism of power, I think. The hall itself—with its almost oppressive symmetry and implied depth—symbolizes the hierarchical structure of the court. All the elements within—the table settings, the columns, even the tapestries in the back—reiterate a message of wealth, authority, and order. It has some connection with "speaking through objects." The print may signify something beyond an event; perhaps aspirations or claims. Curator: And the black and white etching medium is particularly apt for communicating these ideas to wider audiences. Prints like this were circulated amongst the middle classes and gentry, who purchased them for decoration or curiosity, but also consumed this type of propaganda reinforcing absolutist power and control. The symbols that one encounters in "Banquet," such as displayed platters or specific fashion trends of knights, become part of social culture due to reproduction and distribution via print media. Editor: Look closer at the clothing. Note how people's eyes lock, there must be meanings that only the initiated could catch. I sense an undercurrent of subtle signaling via attire that may tell us of specific allegiances. If so, is this then not also an act of visual defiance, given how fashion defies expectations? What appears like mere documentation transforms into layers of messages. Curator: That’s insightful. While documenting fashion and order, Bosse's attention to detail preserved historical information for us, whether intentionally or not. Understanding its symbolic power requires decoding cultural messaging, which, I admit, takes time and study to unpack completely. Editor: Perhaps. I do wonder, if those present were completely aware they formed symbolic entities of power, instead of seeing this merely as yet another gathering? Regardless, the print makes us see history not as a string of events but also cultural code—a script—waiting to be decoded, understood, and then perhaps repeated in altered shapes through time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.