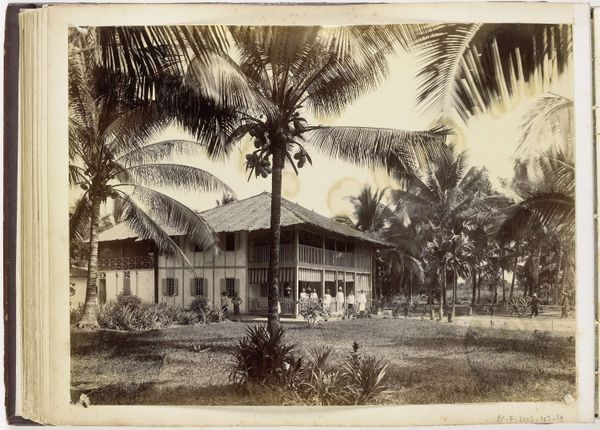

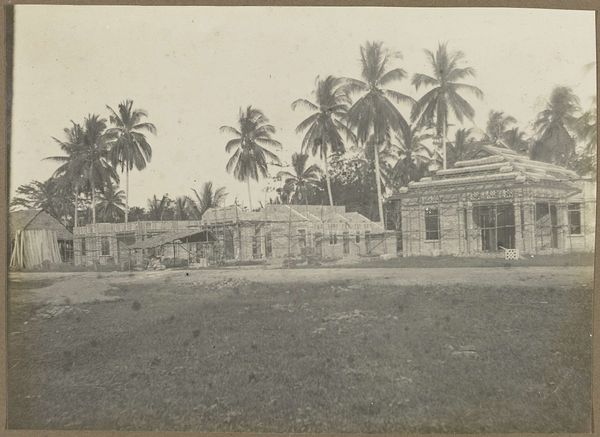

Brussel - Kolonisatiewoning. Links Eucalyptus, rechts ananas, pisang, djagoen 1937 - 1939

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

photo of handprinted image

#

yellowing

#

aged paper

#

yellowing background

#

ink paper printed

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

word imagery

Dimensions: height 145 mm, width 191 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

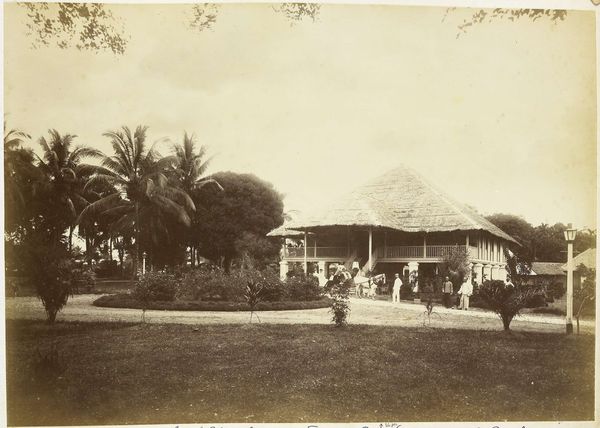

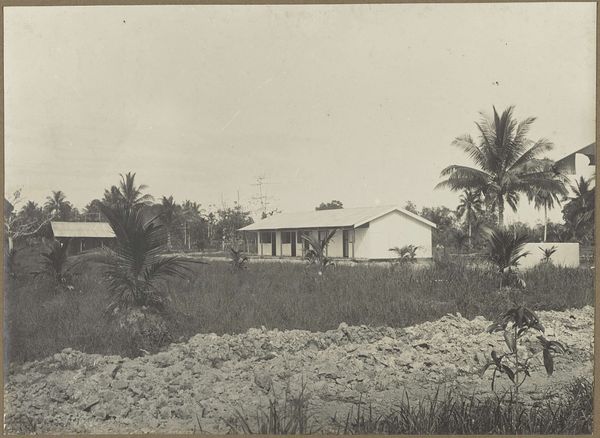

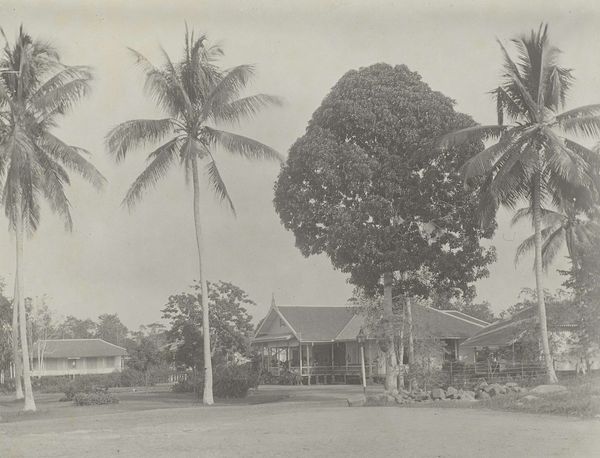

Editor: This photograph, entitled "Brussel - Kolonisatiewoning. Links Eucalyptus, rechts ananas, pisang, djagoen," dates from sometime between 1937 and 1939. It’s a gelatin-silver print. It depicts what appears to be a simple dwelling surrounded by lush vegetation, and I can't help but wonder what life was like for the people who lived there. What stands out to you in this piece? Curator: This image immediately speaks to the power dynamics inherent in colonial photography. The title itself, "Kolonisatiewoning," or "Colonization House," frames the image within a specific socio-political context. We're not simply viewing a house; we’re viewing a symbol of colonial presence. Note the way the exoticized flora, pointed out in the inscription—Eucalyptus, pineapple, banana, sorghum—visually asserts control over the landscape and, by extension, its inhabitants. Editor: So the photograph isn't just a neutral document but rather a constructed representation of colonial ideology? Curator: Precisely. Think about who commissioned or took this photograph and for what purpose. Was it intended to promote the success of colonial projects? To document a specific type of housing? The composition, with the house centered and framed by "exotic" plants, likely served to reinforce a particular narrative for a European audience. How do you perceive the presence and arrangement of the people in the foreground? Editor: They seem almost incidental, like props. They certainly aren't the focus, and they are literally sitting low. Curator: Exactly. They are there, but not centered or even acknowledged. The colonisation house itself is given far more focus. The presence of the children also evokes considerations about their future and how that future is shaped by colonisation. It is a very carefully orchestrated image of power and subjugation. Editor: I never considered how seemingly objective photography could be so loaded with cultural and political meaning. It really changes how I see historical images. Curator: Indeed. This photograph invites us to critically examine the role of imagery in perpetuating colonial narratives and to consider the voices and perspectives that are often silenced or marginalized in these visual representations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.