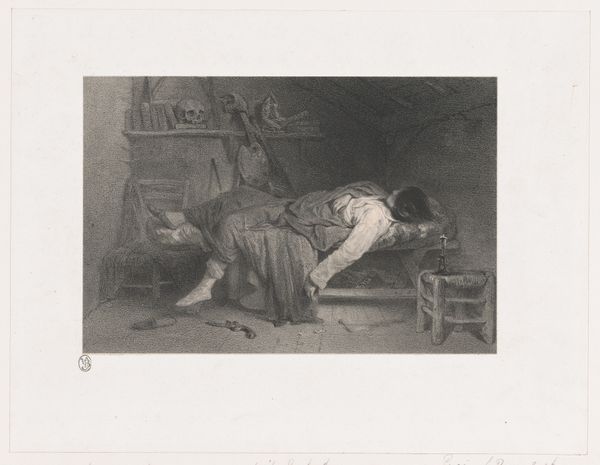

Dimensions: Sheet: 12 3/16 x 15 1/16 in. (30.9 x 38.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

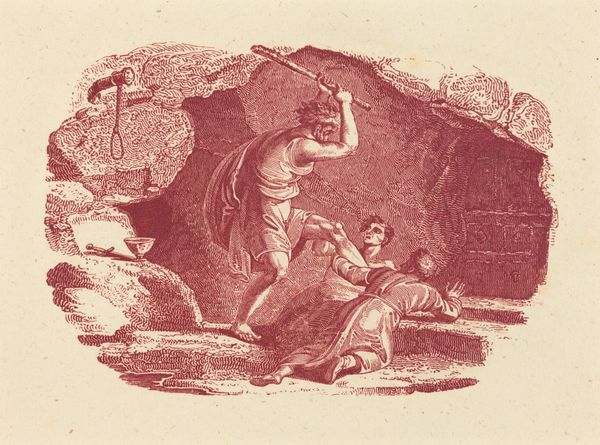

Curator: Before us is Robert Blyth's "The Captive (Sterne's Sentimental Journey)," an engraving from 1781, housed at the Metropolitan Museum. The piece depicts a man in shackles, sitting in what appears to be a dark cell. Editor: It’s striking how the darkness almost swallows the figure. Despite the grim scene, there's a serene quality too, a quiet dignity in the captive's pose that contrasts sharply with the brutal reality of his imprisonment. Curator: That juxtaposition is key. The shackles themselves – a prominent symbol of bondage, are placed upon the ankle; the figure is visually weighted by imprisonment, yet Blyth has rendered him with detail and almost classical beauty. Note the small vessel and implements arrayed on the shelf before him; objects associated with sustenance, reflection and work. Editor: Absolutely. Those elements speak volumes. Is this an attempt to show some agency left for him in his captivity? We have an understanding of what these objects mean to our modern society, but how did they represent sustenance and well-being for others within a long tradition of the past? What stories could they hold within Blyth’s visual imagery? Curator: Consider the light and shadow. The figure emerges from darkness, almost sculpted by the light. Thinkers throughout time saw shadows as representations of what conceals our vision of a true self or being. Blyth gives the face of his captive specific detail, creating an identity where before there may have only been shadow. Editor: You're right; the attention to detail in his face and hands is arresting. He seems burdened not just physically, but mentally too. And I see a link between those symbols and their purpose within narratives of slavery or colonialism where they would represent a stark counterpoint of a culture subdued and repressed by external forces. Blyth shows the subject creating despite of oppression. Curator: Precisely. Blyth is imbuing this individual with an intellectual life, humanizing a figure who, as a prisoner, is stripped of social identity and power. He emphasizes this person's individual consciousness amidst the trauma of imprisonment. Editor: I agree; that visual representation connects deeply to wider social critiques around liberty and injustice, especially during the Romantic period, even within contemporary society. How do the objects inform how people viewed prisons? How did prisons perpetuate slavery after it was supposedly abolished? Blyth allows his viewer a new insight. Curator: Looking closer at the materials and craft, the crisp lines of the engraving lend an immediacy to the subject, capturing vulnerability and perseverance within society. A reminder that images shape our emotional memory and influence culture at large. Editor: A compelling intersection between artistry, cultural memory, and questions of social equity that resonates even now. The artist opens a path of dialogue.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.