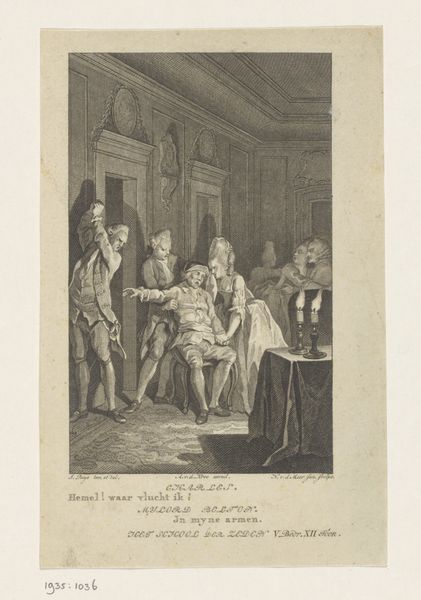

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: 15 x 18 1/4 in. (38.1 x 46.36 cm) (plate)17 1/2 x 22 5/16 in. (44.45 x 56.67 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Ah, "Marriage à la Mode," a print made by William Hogarth in 1745. It's here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Editor: My first thought? It feels staged, stiff. Everyone seems more like a prop than a person, trapped in some gilded cage of obligation. Curator: Hogarth, the ultimate chronicler of the 18th century. This piece, specifically, exemplifies his commentary on arranged marriages and social climbing in that era. Think of it as both genre painting and history painting all rolled into one satirical print. Editor: Satire indeed! Look at that fellow in the chair with the gout-ridden leg and that ghastly family tree. All those folks in wigs squabbling around a small round table as if discussing the finer points of commerce or livestock trade. You get the impression they are trapped like taxidermied animals behind a velvet rope! Curator: Hogarth's skill is quite apparent. Look at how he's using engraving. These intricate lines serve a practical function – prints like this were produced in multiples, made to be disseminated widely, accessible to more than the wealthy elite who could afford an original painting. These etchings had to last and deliver a punch visually with incredible efficiency to an increasingly literate and politically savvy audience. Editor: Precisely! Because the medium mirrors the message, right? A sort of soulless, perfectly rendered transaction to mock… a soulless transaction. Do you see that dog cowering in the lower right? It's the most genuine thing in the whole piece, and he doesn’t even know what a loveless, contracted transaction means for him and his poor little puppy friends. Curator: Note the elaborate interior, reflecting the wealth being negotiated, along with the quality and range of printmaking from that era. All designed for conspicuous consumption. Editor: Ultimately, this reminds me of that nagging feeling after attending some excruciatingly proper high society gathering— the kind where silverware speaks louder than souls and the air smells like old money trying to renew its lease. The whole affair feels like a beautifully executed, yet deeply cynical performance. Curator: Yes, I agree entirely. Hogarth's critique on class and material desires is so pointed here, we see how process mirrors content—reflecting on a society that's becoming overly concerned with appearances.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Inside Lord Squanderfield's residence, the young couple waits helplessly as their fathers sort through the crude terms of their marriage. Seated beneath a ceremonial canopy, Lord Squanderfield points to his illustrious family tree, while the accessories of his gout-the footstool and crutches-are comically adorned with his earl's coronet. He strikes a cultivated pose of nonchalance. The wealthy merchant, by contrast, pours carefully over the documents and money; his simpler dress and stiff posture indicate a distinctly different upbringing. The pretentious young groom is too distracted by his reflection in the mirror to notice the ill-fated advances by Lawyer Silvertongue toward his distraught bride-to-be. In the room's decoration, Hogarth satirizes the fashion for collecting Italian and French pictures, a practice the artist outspokenly criticized throughout his career. In the large mythological portrait in the French style, he represented the earl in the guise of Jupiter, with an exploding canon strategically placed at his groin. The other paintings depict dark subjects-a martyrdom of St. Sebastian, Prometheus tortured by a vulture, Cain killing Abel, Judith with the head of Holofernes-that seem to foreshadow the catastrophic end of this match.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.