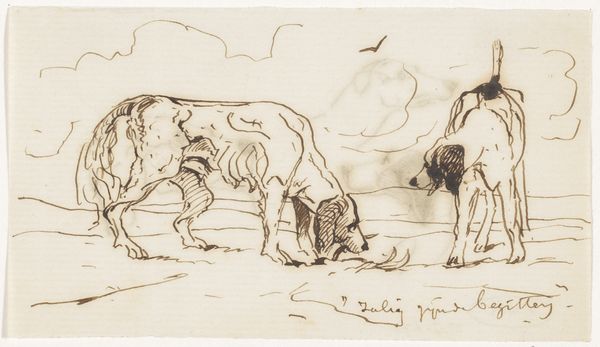

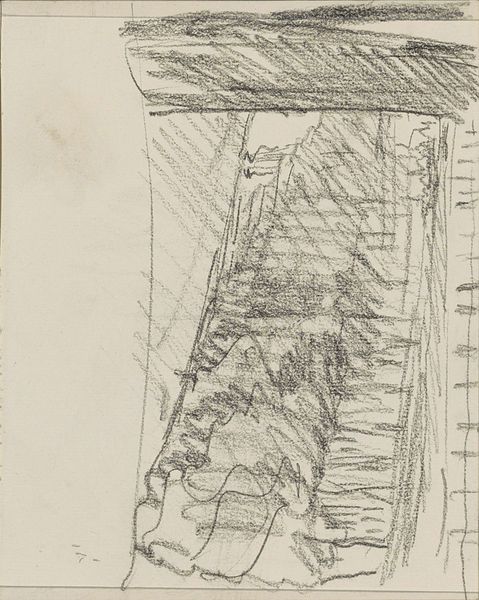

drawing, print, ink

#

drawing

# print

#

figuration

#

ink

#

modernism

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

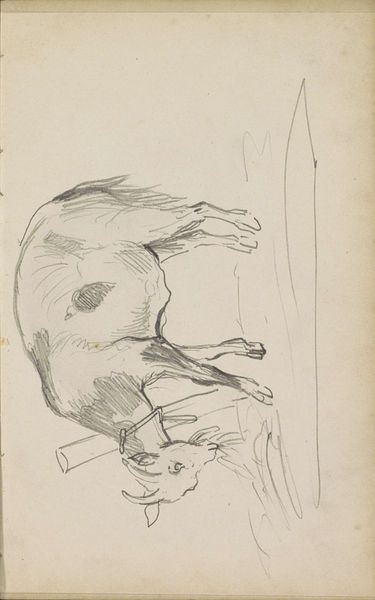

Curator: This ink drawing, entitled "Poultry (La volaille)" created around 1935 by André Dunoyer de Segonzac, presents a still life, though hardly still in the conventional sense. What are your initial impressions? Editor: Well, there's certainly a sense of immediacy and, dare I say, a touch of the macabre about it. The hanging fowl evoke a visceral response – a bit unnerving, yet undeniably compelling. What is your read? Curator: I agree. Death is a powerful, if somewhat unsettling, archetype, represented across centuries. Segonzac uses it to ask, what is meat other than former life? This composition confronts the viewer, and invites consideration of the thin membrane separating life and substance. Editor: Yes, but it also prompts one to reflect on socio-economic strata in interwar France. Segonzac here highlights a reality of procuring, processing and consuming that most were closer to then than they are today. It isn’t just death as archetype but as a record of foodways. Curator: Absolutely, that contextual piece cannot be separated from this artwork. He captures a moment laden with everyday ritual but also shadowed by mortality, rendered simply with the starkness of ink on paper. It taps into a deeply rooted cultural understanding of sustenance. Do you find a cultural ritual or belief mirrored here? Editor: Thinking about its historical reception and legacy, the starkness with which he portrays the dead fowl surely made an impact during a time of both relative peace and looming shadows of war, I mean the artwork acts like a blunt assessment of material conditions. It makes me think of debates around Realism and how art represents real lived experiences. Curator: Indeed, and its seeming artlessness only amplifies its authenticity. Each scratch of the pen feels intentional, imbuing the subject with a sort of austere dignity, even. What's most remarkable, perhaps, is its timelessness. It speaks to us as powerfully today as it must have then. Editor: That's it precisely, I think. In some ways, by refusing to beautify the process of death for consumption, he makes it eternally relevant. He acknowledges an inescapable facet of existence with brutal, elegant simplicity. It really begs one to reflect on what and how imagery impacts us today. Curator: I fully agree; what begins as a mere portrayal becomes an open examination of life and demise. It is rare an artwork can reflect itself across a century this successfully. Editor: Definitely something to ponder as we continue to walk the gallery.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.