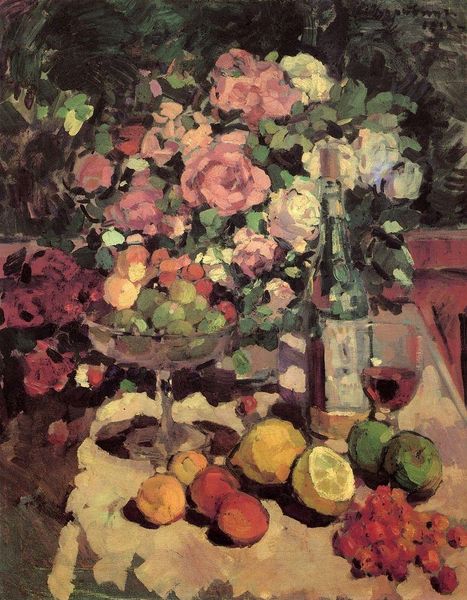

Copyright: Public domain

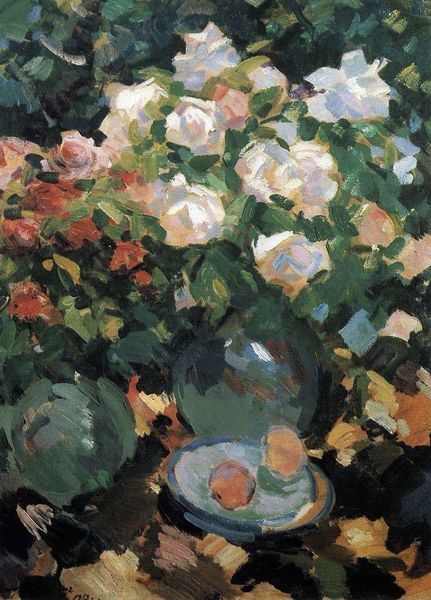

Editor: Here we have Konstantin Korovin’s "Still Life" from 1910. Painted with thick impasto, the objects almost vibrate with color and light. It's a domestic scene, a snippet of bourgeois life maybe? How would you interpret its place within the Russian avant-garde at the time? Curator: Well, it’s important to consider what "avant-garde" actually *meant* in Russia in 1910. This isn’t Paris. Korovin, though exhibiting with groups like the World of Art, inhabited a complicated space. He was both influenced by European trends like Impressionism, as seen in the loose brushwork, yet grounded in representing a particularly *Russian* aesthetic. This painting isn’t revolutionary in a political sense, but the active brushwork and vibrant colors, pushing beyond academic realism, participate in a wider avant-garde push for artistic freedom. Would you agree? Editor: I can see that tension. It’s not outright political or radical like some of the later Constructivists, but there's a definite move away from traditional academic painting. So the flowers and fruit are perhaps symbols of a shifting cultural landscape? Curator: Possibly. Or consider the location - that it's in the Tretyakov Gallery suggests a particular national narrative being constructed around Russian art at this time. Still life, by its very nature, often reflects the values of the society it depicts. Who had the leisure for such opulent displays, and what did that say? Editor: So, the "still life" genre, even in its apparent simplicity, reflects power dynamics of the era. I hadn't thought about it like that before. Thank you for shining a light on how even a seemingly innocuous arrangement can have a history behind it. Curator: Exactly, looking into the institutional and cultural contexts adds so much to the art analysis.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.