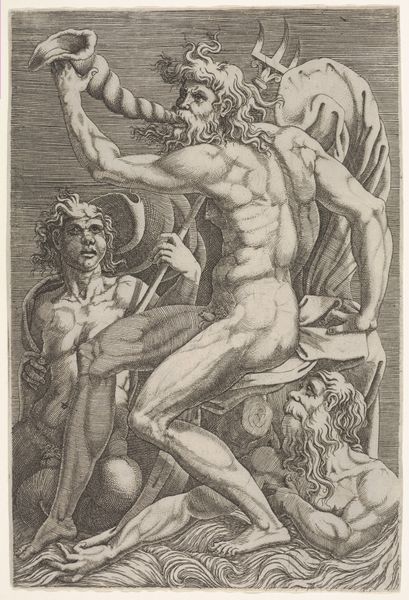

print, engraving

# print

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

mythology

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

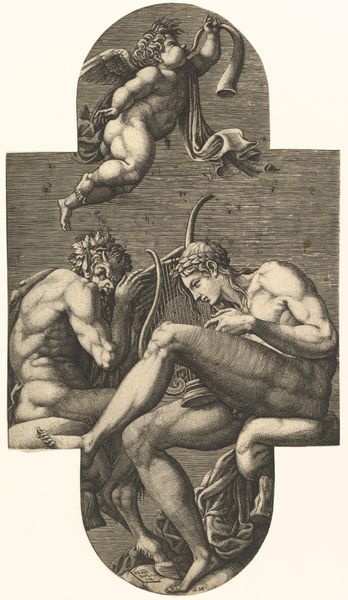

Dimensions: height 291 mm, width 166 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have "Apollo, Pan en een putto die op een hoorn blaast", which translates to Apollo, Pan and a Putto Blowing a Horn. The engraving, now held in the Rijksmuseum, was created sometime between 1541 and 1582, by Giorgio Ghisi. Editor: It’s striking how crisp and clear the figures are, despite the clear age. The scene almost feels crowded within its frame. There’s a strong diagonal sweep from the cherubic figure down to the seated gods, which gives the image a sense of dynamic energy. Curator: I’m drawn to the craft involved. This level of detail would require multiple states, meticulous work on the metal plate. We also have to consider who commissioned it and what purpose it served. Prints like this weren’t just art objects; they were also forms of visual currency. Editor: Absolutely. The narrative, too, needs unpacking. We have Apollo, god of music and light, alongside Pan, the rustic deity of the wild, being watched over by an angel-like putto. This could reflect the tensions between classical ideals and the changing social mores during the Renaissance, or potentially comment on changing spiritual ideas during the period. Curator: I wonder, too, about the practical realities of creating this print. What type of presses did Ghisi employ? How long would such an intricate piece take? Were assistants involved, and what role did they play in realizing the finished product? Editor: Considering those choices, the figures’ exaggerated musculature reflects a Mannerist interest in distorting classical proportions. This, paired with the complex allegorical interplay, may reflect broader cultural anxieties, questioning established hierarchies in both the artistic and social realms. Who did it empower, and perhaps more critically, who did this exclude? Curator: Well, these prints certainly helped spread classical imagery. Though now we are questioning what kind of influence was disseminated to those beyond wealthy artistic circles through these copies, we can still appreciate how meticulously crafted these engravings were as they served both aesthetic and practical purpose. Editor: And by questioning their origins and intended meanings, we engage in the kind of cultural dialogue that keeps the work and its historical impact relevant today. It makes you think.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.