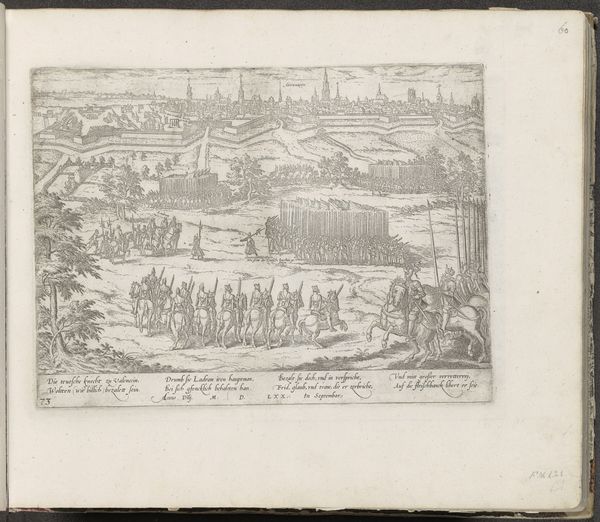

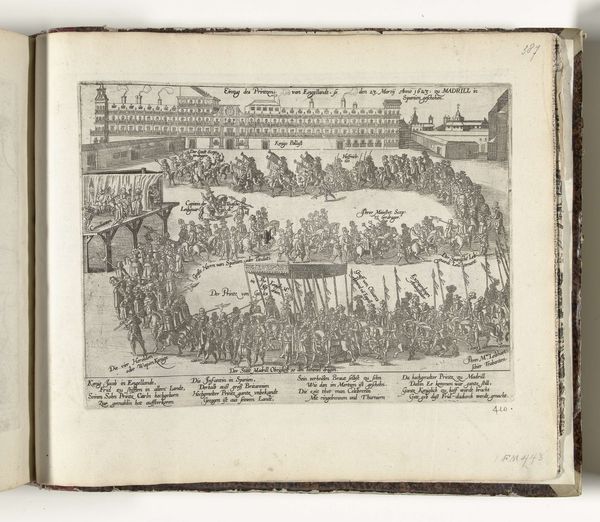

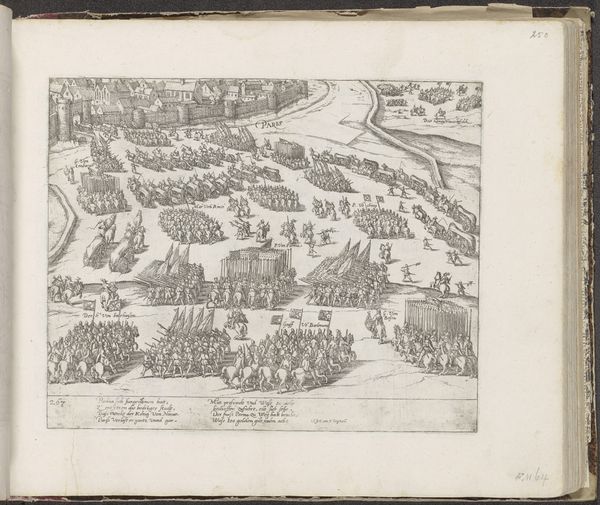

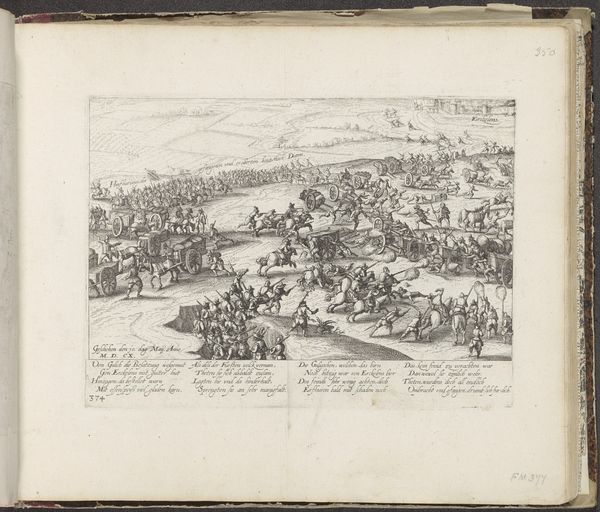

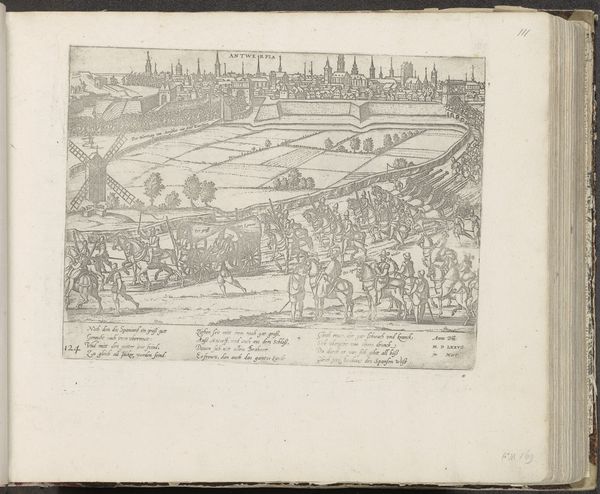

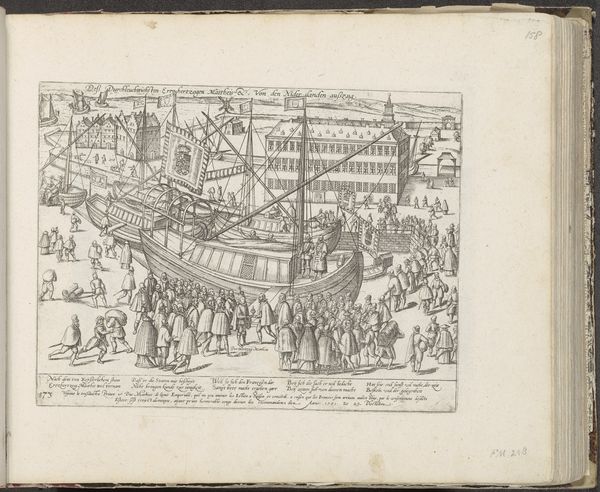

Beleg van het kasteel van Wouw bij Bergen op Zoom, 1583 c. 1587 - 1591

0:00

0:00

franshogenberg

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

# print

#

mannerism

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 217 mm, width 274 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. We are looking at a print currently housed at the Rijksmuseum. It depicts the "Siege of Wouw Castle near Bergen op Zoom, 1583," created around 1587 to 1591, by Frans Hogenberg. This piece exemplifies the Mannerist style, rendered in detailed engraving. What's your immediate impression? Editor: Chaotic! It's a blizzard of tiny people. And I'm drawn to the somewhat bird's-eye perspective—you get a real sense of the enclosed space, the claustrophobia of the siege itself. Visually, it feels a bit like a stage set, doesn't it? Curator: That staged feel is partly due to the Mannerist aesthetic, a style known for its artificiality and theatrical composition. Consider its historical context: these prints, part of a series, were essentially the news media of the day. Hogenberg’s prints played a critical role in shaping public perceptions of the Dutch Revolt against Spanish rule. Editor: News media... but, also, powerful propaganda! Those captions certainly feel like someone making their point! Did folks at the time question its reliability, or just gobble it all up? It feels… biased, let’s say, at a first glance. Curator: Doubtless, bias was built-in. However, that does not make it a totally worthless source. Though perhaps overly stylized, the images convey specifics about warfare. Notice the details—the cannon placements, the fortifications. These reveal more practical approaches to siege warfare and defensive infrastructure during the late 16th century. Editor: So, it is a picture that aims to give news, yet still it gives an "angled" version? It shows both warfare and also how power functions and reproduces the reality of that power dynamically. It also makes me consider how much more complex capturing these realities are, from a contemporary point of view. The quality and nature of the experience changed for both artist and witness. Curator: Indeed. What seems initially to be merely a detailed scene of conflict then emerges as something complex, and historically relevant beyond purely battlefield depictions. It encourages to us reconsider both how the public views art and how historical context dictates and molds not only the narrative portrayed, but also reception. Editor: Yes! Art isn't created, displayed, or received in a vacuum. By thinking critically about art and power, it all connects us a little bit closer to both then and now. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.