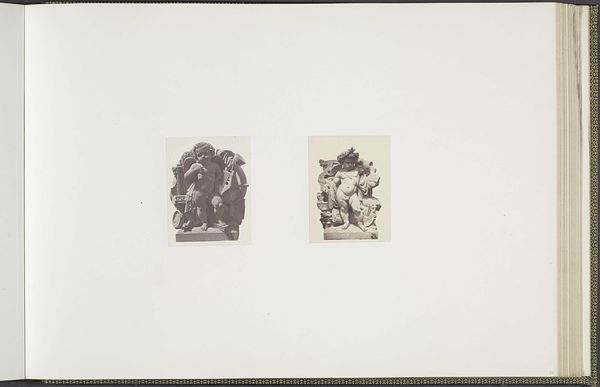

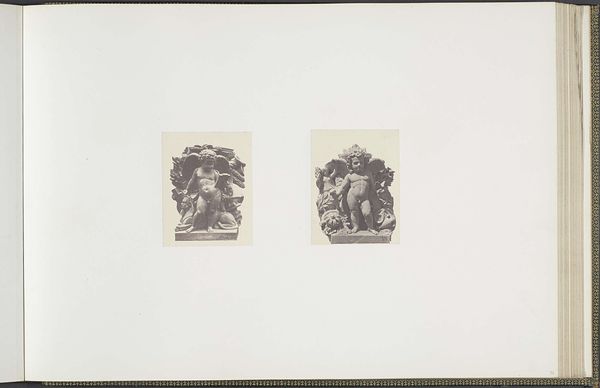

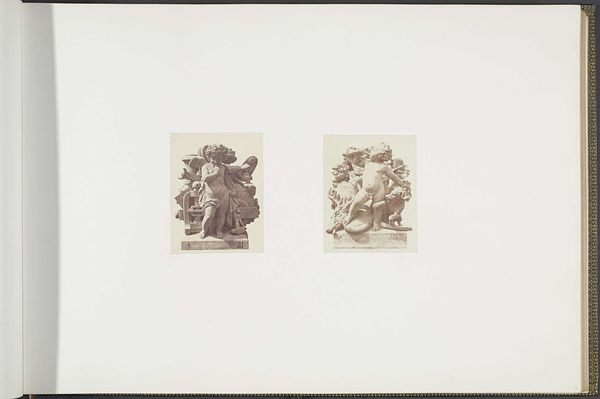

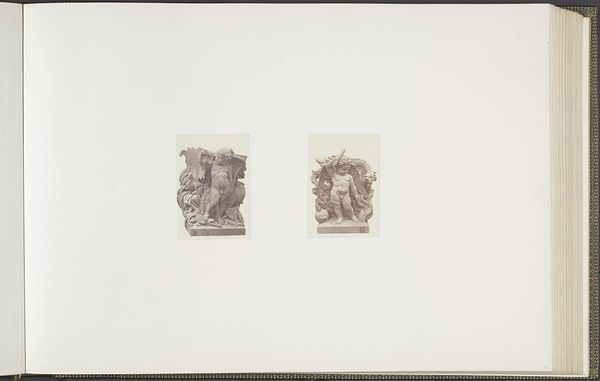

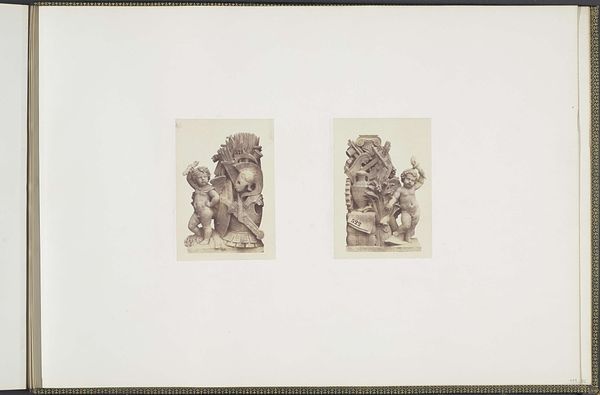

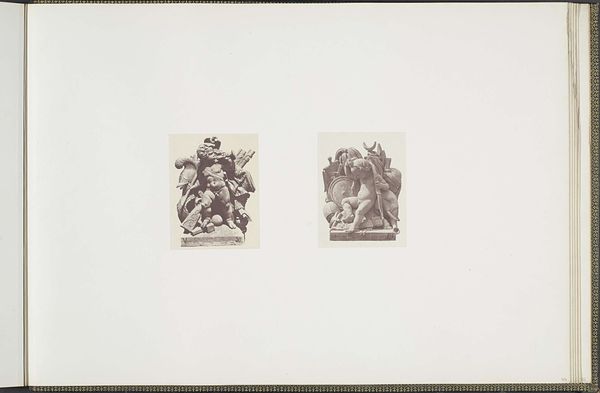

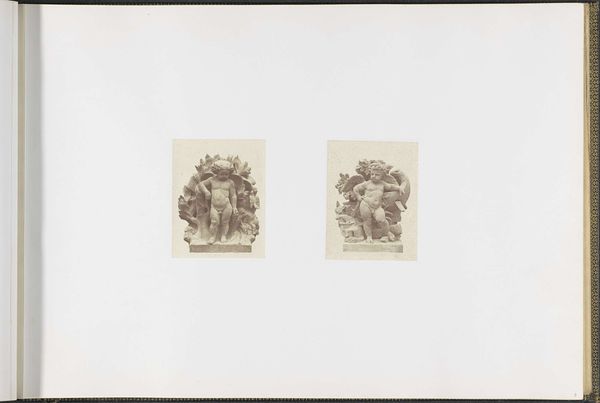

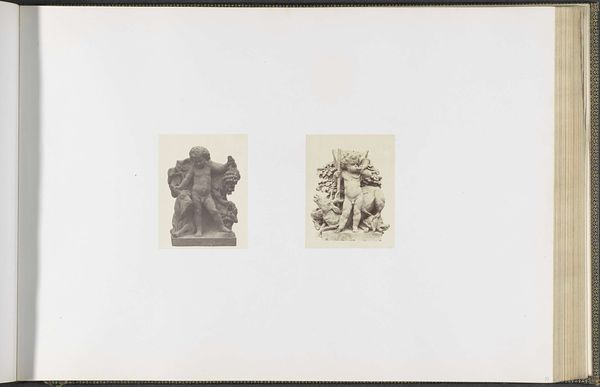

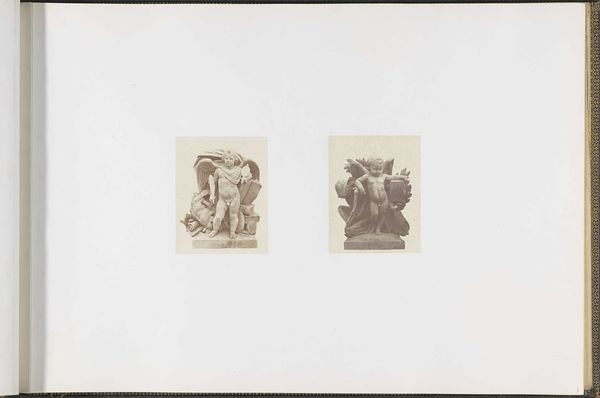

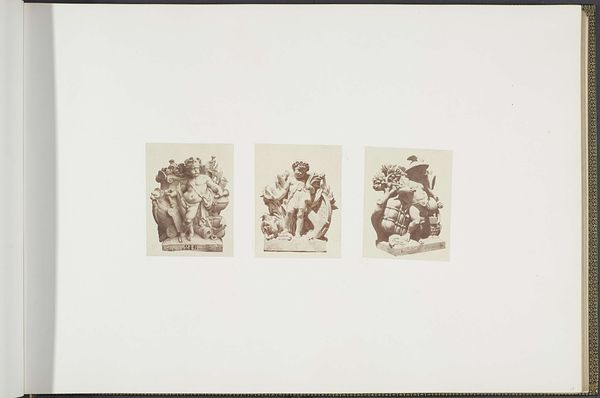

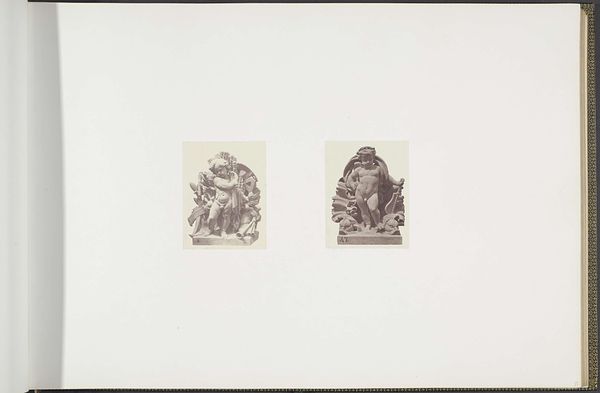

Gipsmodellen voor beeldhouwwerken op het Palais du Louvre: links "Les Combats" door Jean-François Soitoux en rechts "La Force" door Armand Toussaint c. 1855 - 1857

0:00

0:00

print, photography, sculpture

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

photography

#

sculpture

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 382 mm, width 560 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Edouard Baldus’s photograph, "Gipsmodellen voor beeldhouwwerken op het Palais du Louvre," taken around 1855 to 1857. It presents, side by side, images of plaster casts intended for the Louvre – sculptures of, I think, childlike figures. The whole composition feels very official and academic. What's your take? Curator: It’s fascinating how Baldus's photograph engages with the very construction of French identity in the mid-19th century. The Louvre, more than just a museum, was a symbol of national pride. By photographing these preparatory plaster casts of *Combats* and *La Force* meant for its facade, Baldus subtly reveals the ideological work that went into crafting a heroic narrative for the nation. Editor: Heroic how? They look like cherubs, or *putti*. Curator: Precisely. Think about the broader political climate – the rise of Napoleon III and the Second Empire's quest for legitimacy. The placement of these sculptures on the Louvre contributes to a deliberate construction of a glorious historical lineage. These seemingly innocuous figures of childhood and innocence – in a classical style, might I add – cleverly soften what would otherwise be overt and possibly provocative imperial messaging. Consider who funded such artwork and where such artworks were intended to be seen. Editor: So the museum itself becomes a stage, reinforcing the emperor's power through carefully chosen imagery. That's powerful stuff. Curator: Indeed. Baldus, in turn, by documenting this process, isn't just creating a record, but participating in this careful staging of French power. It forces us to confront how photography, art, and architecture worked together in 19th century public spaces to legitimize socio-political agendas. Editor: It makes me realize how art can serve purposes beyond just aesthetics or beauty, really solidifying a certain national idea. I never thought about those cute sculptures that way. Curator: Absolutely. I find myself appreciating how a photograph, like Baldus's, prompts us to examine these public facing facades to think more about politics, nationalism, and hidden symbolism.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.