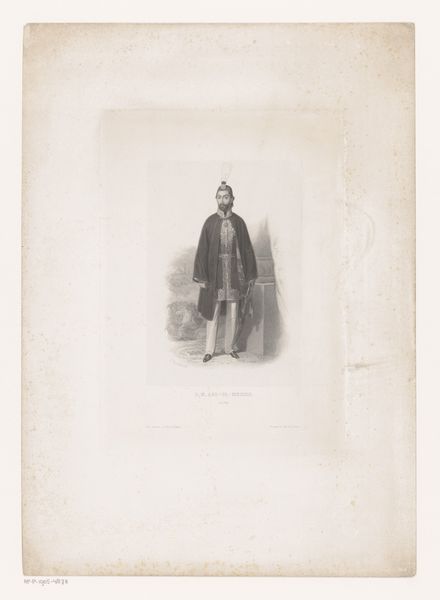

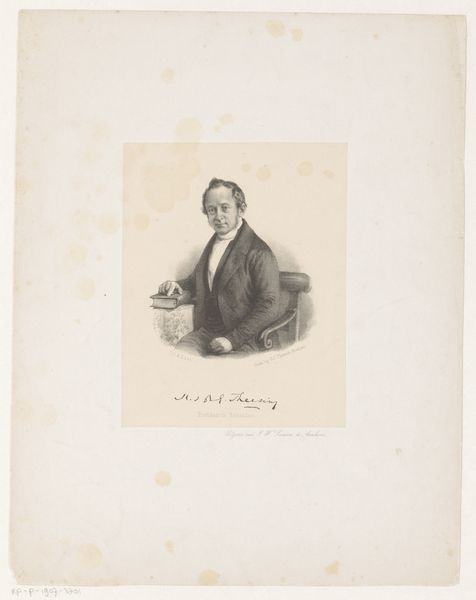

drawing, lithograph, print

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

lithograph

# print

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 510 mm, width 345 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we see a lithograph drawing created sometime between 1843 and 1845 by Paulus Lauters titled, "Portret van Adi Patti Mandura." It is currently housed at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My immediate impression is one of subdued authority; the neutral palette and somewhat severe expression convey a sense of formality. Curator: Indeed. Considering the printmaking process involved in lithography during this period is crucial. The artist had to meticulously transfer the image onto a stone or metal plate, making this image potentially widely distributed. This inherently alters our perception when comparing it with a unique portrait. Editor: Precisely. This hints at the subject's status but also raises questions of accessibility and circulation within colonial power structures of the time. Adi Patti Mandura—how does his Javanese identity intersect with this formal Western style of portraiture? Curator: His traditional Javanese headdress offers a distinct visual marker amidst the European clothing and style of the portrait. We should look closely at the materiality and labor required to produce and reproduce these lithographs, the implications for distribution networks of imagery across colonial contexts, and the labor needed for printmaking during this era. Editor: This blending certainly provokes a deeper reflection on identity and representation under colonial rule. What narratives might this image have perpetuated, and for whom? Curator: By dissecting the mechanics of this artistic production—the precise methods and intended recipients—we can better assess the impact this kind of image might have had on circulating and standardizing cultural power. Editor: Absolutely, this helps to emphasize that even portraits seemingly intended for commemoration were active agents in social processes, reflecting, reinforcing, or even subtly challenging prevailing social power balances of colonial Dutch society. Curator: Investigating the social conditions surrounding artistic production always sheds invaluable insight to pieces that, on their own, might seem merely formal likenesses. Editor: For me, the image offers a rich starting point to consider identity, colonialism, and cultural negotiation. It goes beyond a simple likeness; it becomes an embodiment of intersectional experiences.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.