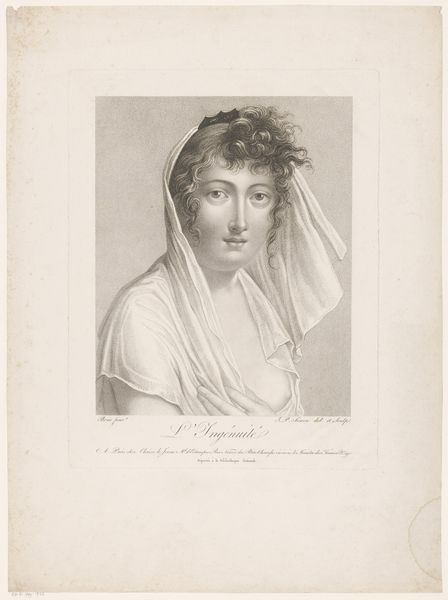

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

caricature

#

charcoal drawing

#

historical photography

#

portrait reference

#

pencil drawing

#

portrait drawing

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 378 mm, width 275 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us, we have Charles Howard Hodges' 1785 engraving, "De maitresse van Raphael," housed here at the Rijksmuseum. It presents a poised female figure, elegantly framed within sharp lines and muted tones. What’s your initial take on it? Editor: It's remarkably serene, yet there's a theatrical air about her. Her headwrap and attire evoke an almost Orientalist vision, but executed in a rather classical style. There's a story here, shrouded in those heavy fabrics and that sidelong glance. Curator: Absolutely. Hodges created this print during a period of intense interest in portraiture within elite social circles, where depictions often reinforced social status and intellectual aspirations. It was the age of enlightenment, with people seeking inspiration from earlier historical epochs of purported cultural achievements. Prints such as these allowed wider circulation of those portraits. Editor: The title identifies her as Raphael's mistress. That choice carries substantial symbolic weight. Raphael was a key figure in Renaissance art, symbolizing ideal beauty and artistic genius. Naming her his "mistress" links her, visually and conceptually, to notions of artistic inspiration and female allure—potentially even suggesting an "archetype" of feminine beauty associated with artistry. Curator: True, the association elevates her beyond a simple portrait. But consider how this kind of representation could be perceived politically. Referencing a historical figure in the mistress-portrait format implicitly endorsed particular patriarchal norms of the late 18th century. It normalizes female subjects by association, filtered and consumed through the male gaze. Editor: Precisely! Her turban and dress themselves speak volumes. Headscarves, depending on cultural context, have signified virtue, mystery, exoticism… they offer layered readings related to gendered presentation of the self, of power, and otherness. And how she glances sideways also offers possibilities. Is she wistful, alluring, melancholy, compliant? Curator: And prints like these aided the commodification and distribution of such imagery, influencing perceptions across different classes. The mass distribution through engravings and similar printing processes impacted what ordinary people imagined "beauty" to be. Editor: The print carries so much encoded history within its strokes—linking feminine ideals, exotic fantasy, and the commercialization of artistic legacy. Thanks for giving the image added layers. Curator: The power of images is pervasive. Thanks for unpacking this portrait’s symbols so thoroughly.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.