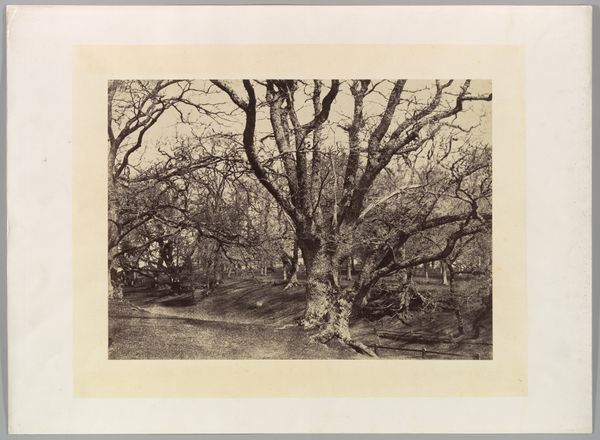

photography, albumen-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 220 mm, width 278 mm, height 357 mm, width 450 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

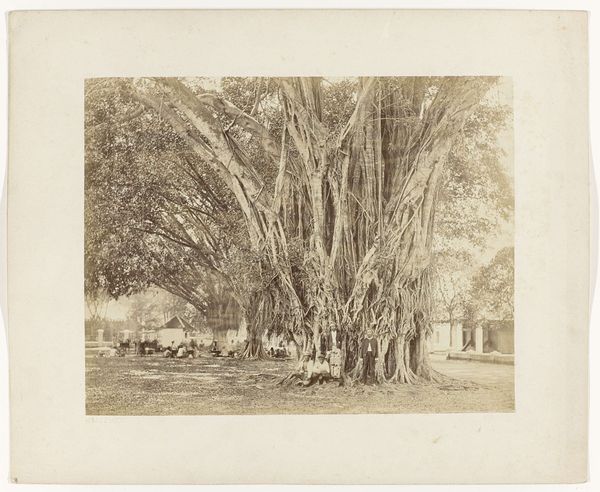

Curator: Let's turn our attention to "Abraham's Oak, Mamre, Palestine", an albumen print by Maison Bonfils dating from somewhere between 1850 and 1900, currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It has a very elegiac tone, doesn't it? That central tree, stripped bare of most of its leaves, dominates the composition, a solitary witness. Curator: Precisely. The formal aspects draw our eye upward; the strong verticality, softened by the graceful curve of the branches. The light, that near-sepia tone afforded by the albumen process, imbues it with a kind of...distilled essence of the historical, or maybe mythical past. There's also an interesting tension between the sharply defined foreground and the somewhat softer focus of the landscape. Editor: The albumen process is key, isn't it? Think of the material realities—the egg whites carefully coating the paper, the silver nitrate sensitizing it to light. It transforms the scene, giving a kind of elevated timelessness, doesn’t it? Who exactly was this Maison Bonfils and their practice? And it makes you wonder about the workers involved in producing the photograph—their labor, their wages. It’s a constructed image but through very tangible materials. Curator: Maison Bonfils was a photographic studio in Beirut, significant in creating Orientalist imagery of the Middle East. The framing here lends the scene a somewhat constructed picturesque quality, almost staging the tree as an object. The bare branches are strategically placed for dramatic effect against the distant landscape. One might explore the philosophical meaning of it and its position in historical record. Editor: Certainly, its construction raises valid considerations. These kinds of images promoted a specific view of the Middle East, often consumed by Europeans eager for exotic imagery. By understanding the context of how it was made and who was consuming the final object reveals not only an artist’s aesthetic interest but also something about nineteenth century class, and empire. Curator: Ultimately, what strikes me most is how the photographer’s choices frame our understanding of place and identity. The tension in that visual dance is undeniable. Editor: And considering the choices inherent to the materiality and social context opens our understanding even further; It leaves us pondering what traces—social, economic, material—linger within the image itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.