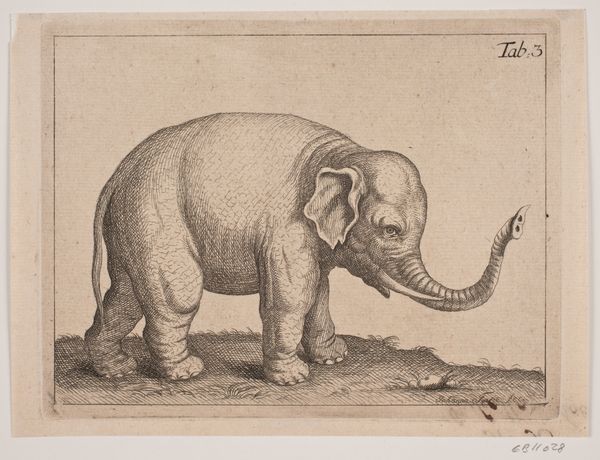

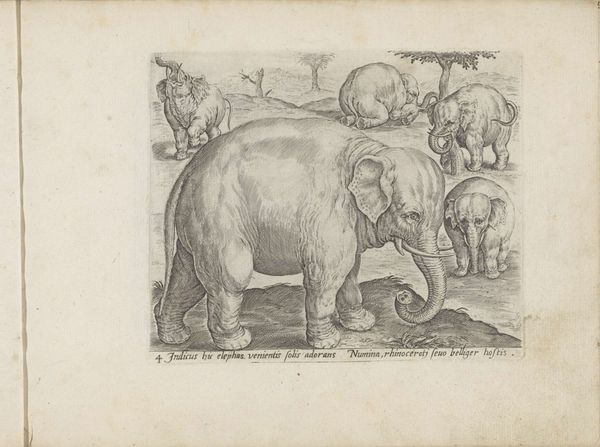

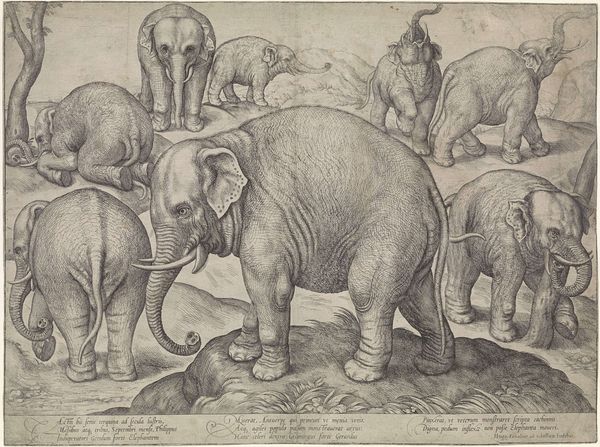

drawing, print, engraving

#

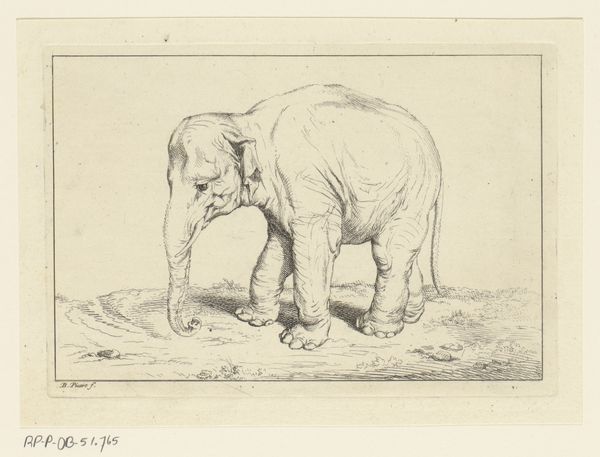

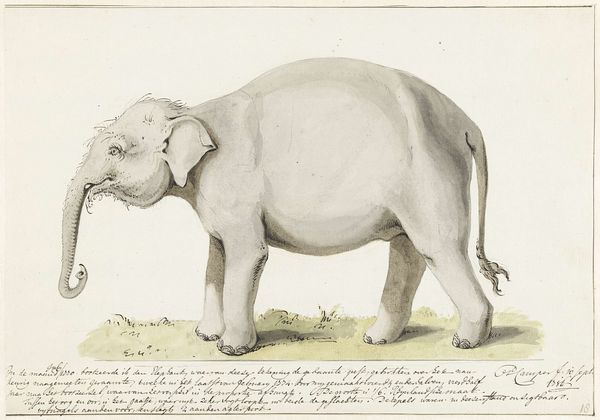

drawing

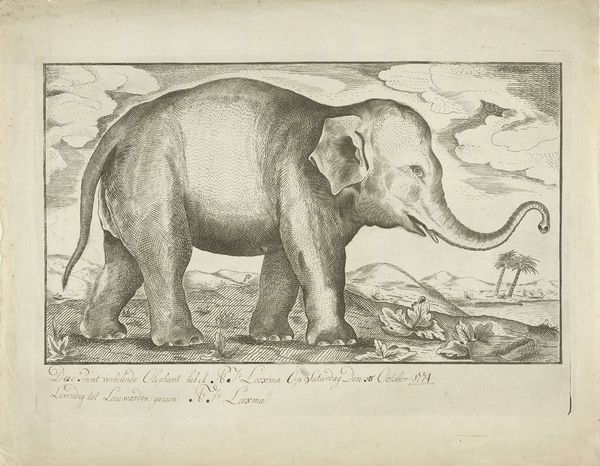

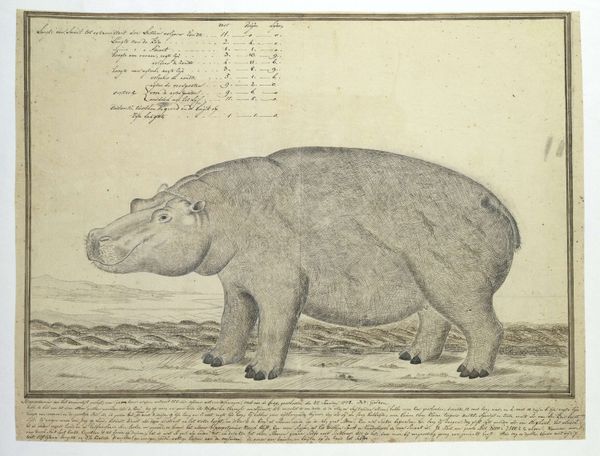

# print

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

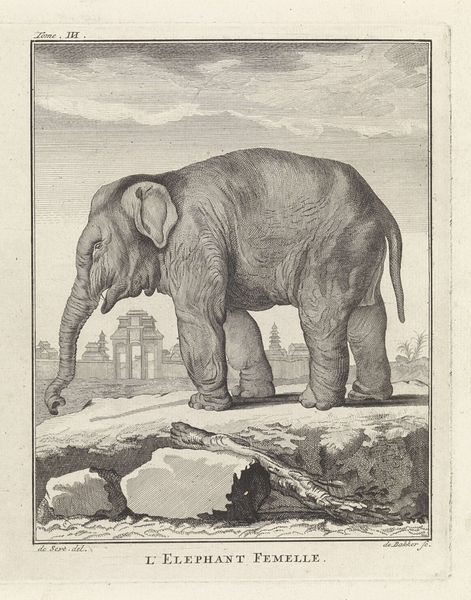

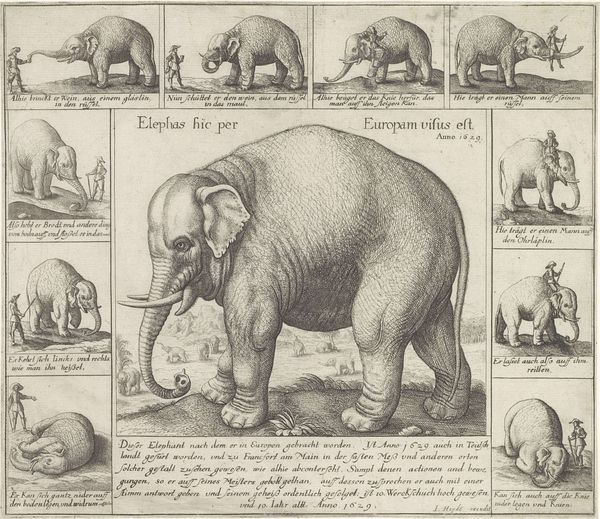

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: sheet: 7 15/16 x 8 3/4 in. (20.2 x 22.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Standing before us is "A Young Elephant," an engraving by Johann Heinrich Tischbein the Younger, created sometime between 1750 and 1808. It's currently housed here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It strikes me as remarkably docile, almost subdued. The monochromatic palette and precise lines give it a sort of scientific observation feel. The lack of background isolates it. Curator: Exactly. Let’s consider the production of such an image. Engravings are meticulous, requiring a skilled hand to transfer an image onto a metal plate, then print it. It reflects the 18th-century interest in cataloging the natural world and displays of exotic animals, and the growing menageries were an industry reliant on both the acquisition and captivity of non-human animals for spectacle and science. Editor: Agreed. The formal composition certainly underscores that aim. The stark simplicity in rendering—note the almost clinical detail in its hide—pushes the essence of "elephant-ness." There’s also this use of line to construct volume, implying weight and mass that belies the flat surface. Look closely and it’s like the artist used language instead of chiaroscuro. Curator: Precisely. Think about what this meant socially: a detailed, reproducible image allows for the wider dissemination of this "knowledge," impacting the cultural understanding and, potentially, exploitation of these animals. Engravings, therefore, served not just aesthetic purposes but functioned as crucial tools in shaping our perceptions. Editor: Interesting...it also speaks to the Enlightenment’s attempt to capture and dissect the natural world through art and science, attempting a kind of mastery via representation. Is it successful here though? Does it reduce this creature to a set of characteristics? Curator: Perhaps that tension—between objective observation and the living essence of the animal—is what makes the piece so compelling even today. Editor: Yes, between science and sensitivity. A reminder of the lens through which we've historically—and continue to—regard the non-human world. Curator: And of the tools used to further the expansion of such industry in its early beginnings. Editor: So even in something that seems so simple, so docile as an artwork can reflect the much broader history and dynamics surrounding the relationship to commodity, knowledge, and natural order. Curator: Absolutely, it opens our perspective of the era's developing scientific exploration in service of colonialism.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.