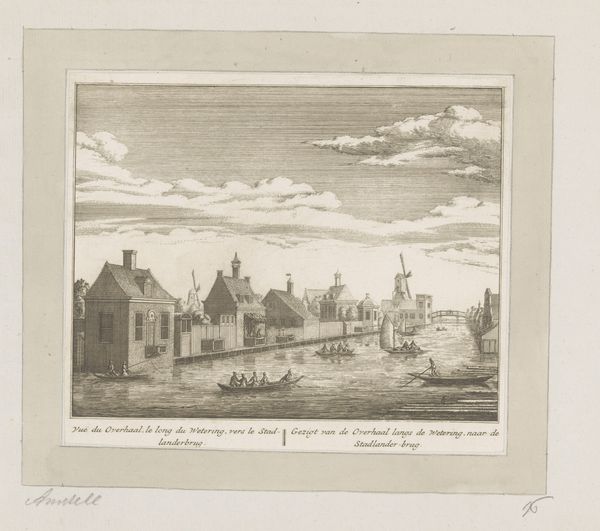

print, engraving

#

neoclacissism

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 175 mm, width 245 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at "Gezicht op IJsselmonde," made between 1786 and 1792 by Carel Frederik Bendorp, I'm immediately drawn into its surprisingly active stillness. There's a serene yet busy quality. Editor: The landscape itself looks unassuming. What’s interesting to me is that this piece, an engraving on paper, a print really, provides access to this scene, allowing for broad distribution of images in a way painting or other singular forms can't. Consider the act of witnessing transformed by reproductive technologies! Curator: Exactly. We’re situated in a period moving toward revolution. Let’s consider what access to these scenes—views of waterways with people of various classes, industry existing beside leisure—might mean for social consciousness and perhaps even anxieties of the era. We need to acknowledge who is present and who isn't, focusing on labor distribution by gender, race, and socioeconomic status within 18th-century Holland. Who profits and at whose expense? Editor: I appreciate the gesture toward a broader reading of labor; I would also want to point toward the engraver themselves. Bendorp has mastered his materials in order to produce this image, carefully controlled line work making it easy to see a scene otherwise inaccessible. Printmaking demands its own specific labor process. How is craft used in image-making to establish political narratives? Curator: Yes, and looking at these crisp lines, one cannot ignore the strong influence of neoclassicism present in the artist’s overall aesthetic; and in particular, Bendorp gives the viewer such detail which is exemplary of art of the Dutch Golden Age! Editor: True, but that technical precision—the clean lines, the controlled perspective—is at the service of a specific way of seeing. Are we truly getting an accurate "view," or a constructed reality, idealized and made widely available? Curator: I think that tension is precisely what makes this print so compelling: a reflection on Dutch society right before radical transformations. I am now curious to return to how prints of these subjects and class dynamics reached wide audiences. Editor: Agreed, and for me this opens questions about the role and meaning of printmaking beyond the context of “fine art.” Considering the process and distribution might enable different insights, not just to Dutch life in the late 18th century, but on our understanding of how art becomes entwined with ideology and politics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.