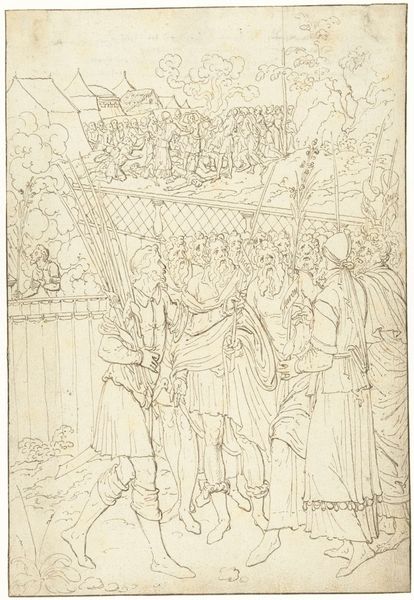

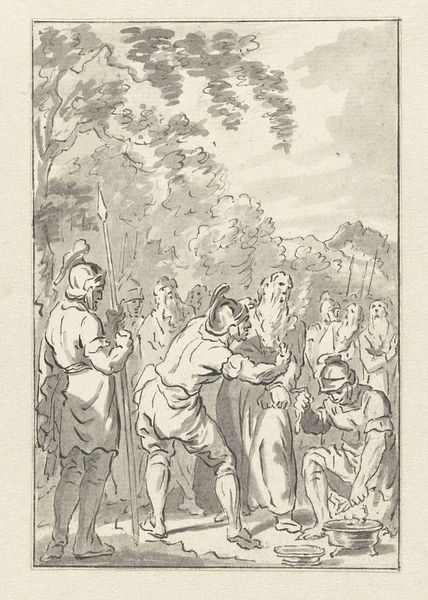

drawing, paper, ink, pen

#

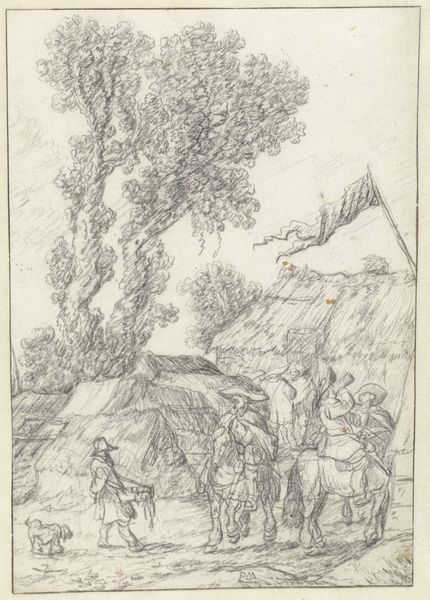

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

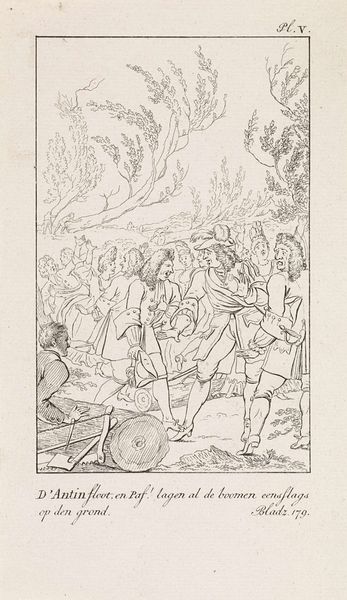

pen illustration

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

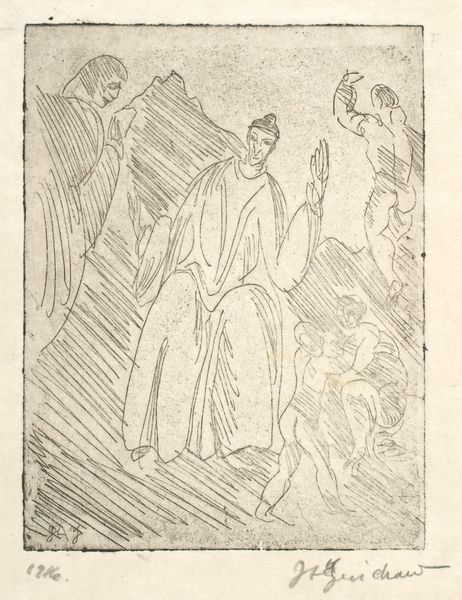

paper

#

ink line art

#

ink

#

pen

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 117 mm, width 70 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have "Ruth, Boaz en een opzichter werken op het land" which roughly translates to "Ruth, Boaz and an overseer working the land". This ink and pen drawing on paper was completed sometime between 1798 and 1837 by Ernst Willem Jan Bagelaar. Editor: It’s the linework that strikes me first. So spare, so direct. A very clear sense of implied form is at play, especially within the draped fabrics. There’s an undeniable crispness despite its age. Curator: Absolutely. Consider how Bagelaar's employment of line—its weight and variation—shapes the narrative. Observe how the pen, in his practiced hand, doesn't merely depict; it articulates the relationship between labor, the body, and the landscape, echoing a genre scene while subtly referencing biblical narratives. Editor: Given that it’s a biblical subject matter and appears to be made with pen and ink, I’m wondering about printmaking's impact. This piece could be a study for something grander or even a standalone piece reflecting the period’s print culture and how biblical stories permeated even quotidian artistic output. The choice of materials surely was part of how this was intended to reach a public audience. Curator: Indeed. It evokes a pastoral idyll—a theme common in art historical landscapes—yet the active figures introduce a tension, a reminder of work, production, and the socioeconomic realities of the era. Look at the body language! They do not relax within the composition but rather act and labor within it. The landscape itself, while bucolic, is tamed by their activity. Editor: Yes, and the roughness of the execution in certain areas is worth noting; there is very little fussiness here, unlike fine art painting. There is a utilitarian aspect to the materials chosen as they suit rapid depiction and reproduction, so perhaps something ephemeral rather than intended as an end in itself. Curator: One could read the ink work as allegorical. Black ink representing knowledge—especially religious knowledge due to its textual association—and its placement over a white background reflecting an attempt to bring enlightenment. The formal constraints force our perception of spatial depth. Editor: This tension that you discuss and its material presence lead me to question its reception back then. We can only speculate whether it affirmed social order, inspired piety, or merely aesthetic admiration; still, it's intriguing to imagine what meanings audiences extracted given the historical moment. Curator: Precisely. It speaks of artistic practice, societal values, and the powerful resonance of visual language across centuries. Editor: A testament to how material choices often echo broader cultural narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.