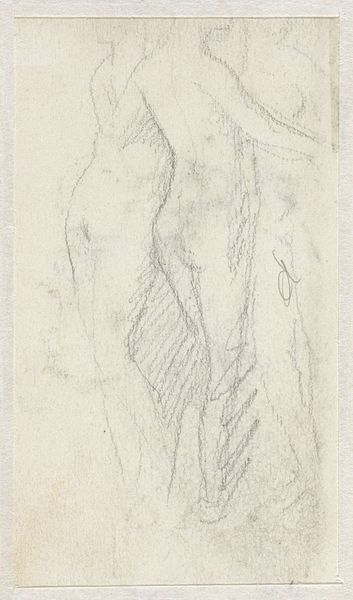

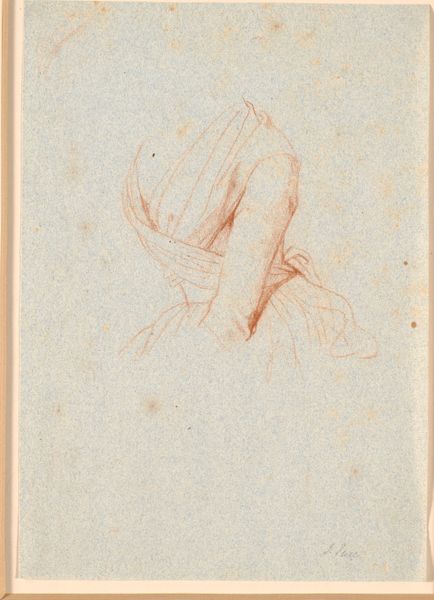

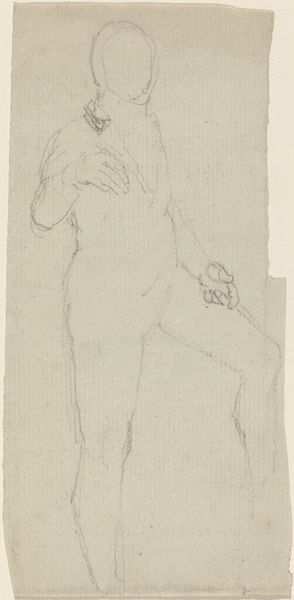

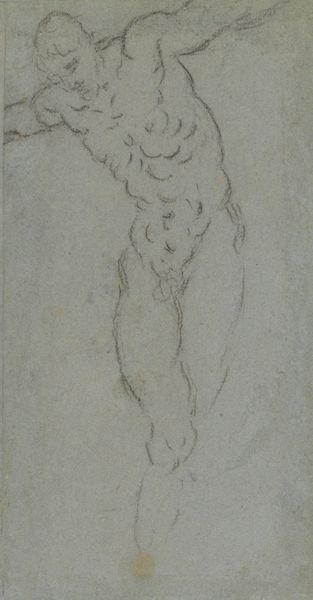

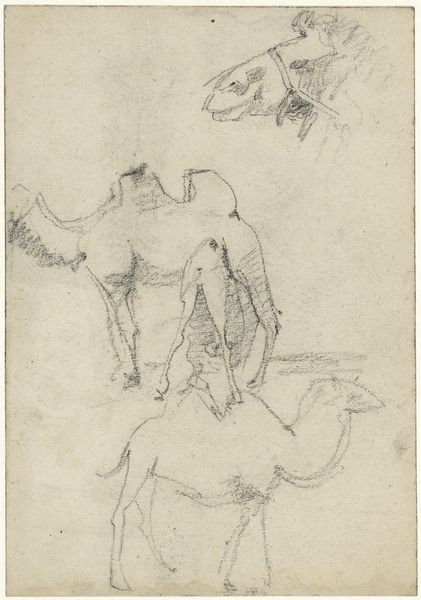

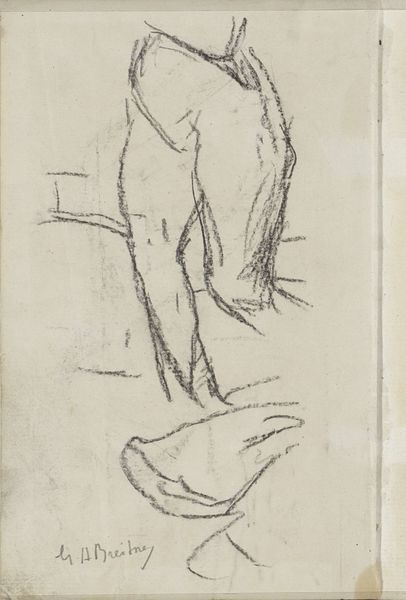

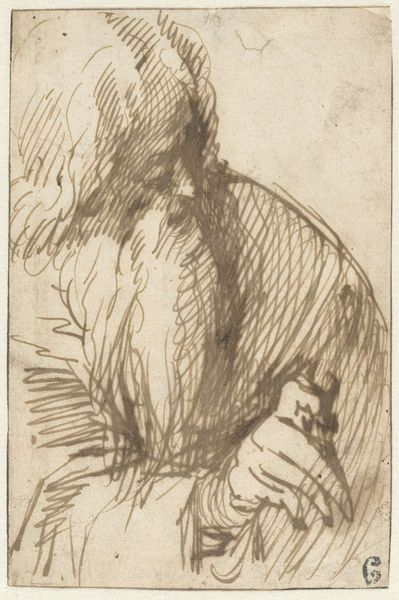

drawing, print, paper, pencil, charcoal

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

paper

#

pencil drawing

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

charcoal

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

nude

#

watercolor

Dimensions: 129 × 338 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This drawing, “Studies of Nudes” by Henry Fuseli, appears to be a pencil sketch on paper. I’m immediately struck by the roughness of the paper, and the sketch-like quality. How can we interpret this piece considering its apparent lack of refinement? Curator: Well, let's think about the means of production here. Fuseli's choice of materials – pencil and paper – suggests a preliminary stage, a study rather than a finished artwork. The torn edge reinforces this sense of process, of something incomplete or even discarded. Doesn’t this challenge the conventional view of art as a polished, final product? Editor: Absolutely! It does make me question what Fuseli considered valuable or worth presenting, since it could also be viewed as purely utilitarian, perhaps an exploratory practice. Curator: Exactly. Consider the social context. In Fuseli's time, academic art placed high value on finished, history paintings. However, artists often relied on drawings like these to develop their ideas. What labor do we not see that might've been present in completing something more, or that went into preparing his materials? What statement might the artist be making with this presentation? Editor: So, is this drawing then a subtle commentary on the art market itself, by focusing our attention to materials rather than its artistic polish? A protest, in a way, against high art? Curator: Possibly. By emphasizing the materiality and the labor involved, he invites us to reconsider our assumptions about artistic value and production. What does consumption of this incomplete work say about us as its viewers, centuries later? Editor: That’s a really interesting take. I never considered the artwork’s deliberate incompleteness in such detail. It shows how materials and production can indeed be central to a work's meaning, if only to make that message clear. Curator: Precisely. By examining the “how” and “what” of the work, we can better understand its relationship to society and its challenges to established norms.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.