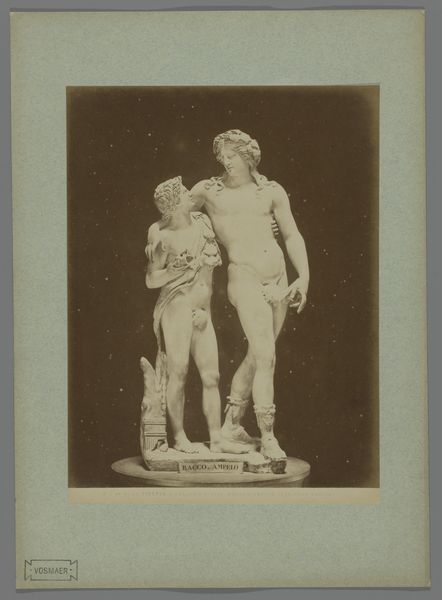

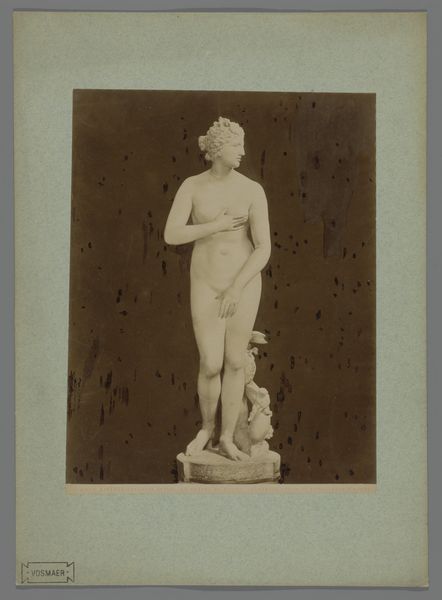

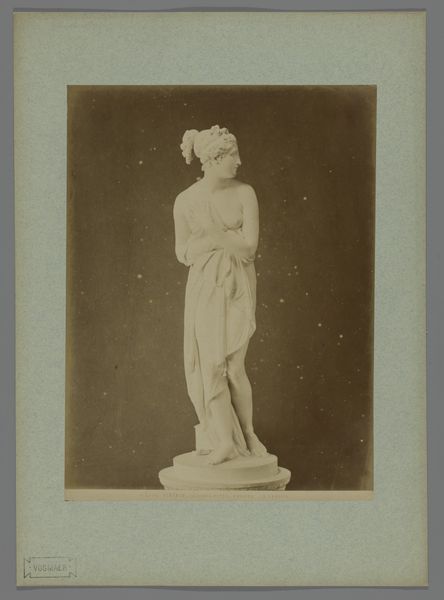

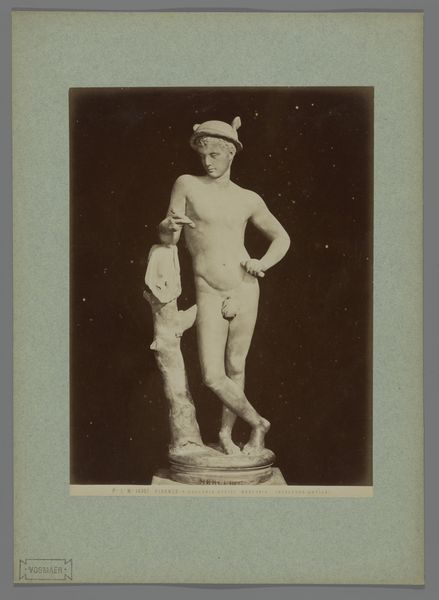

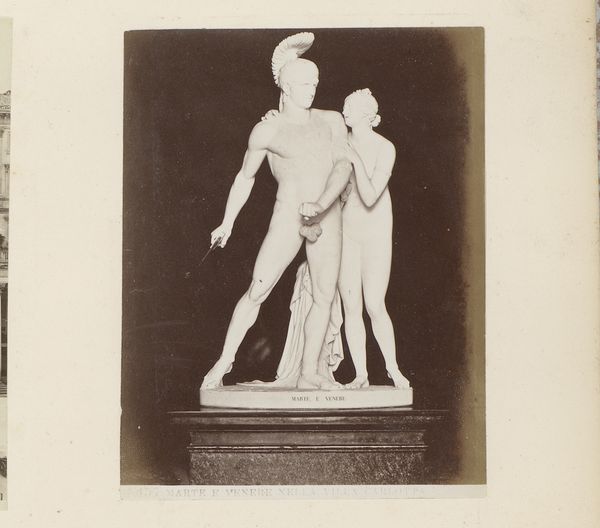

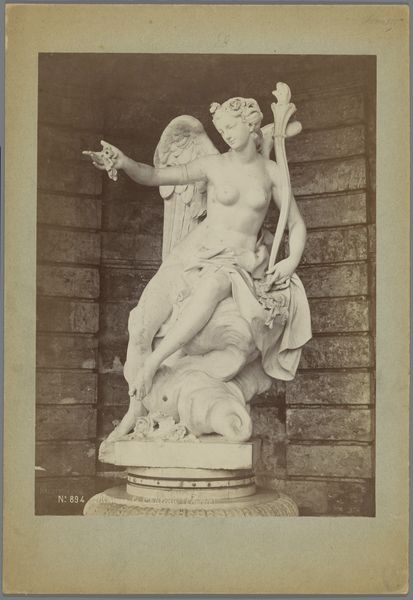

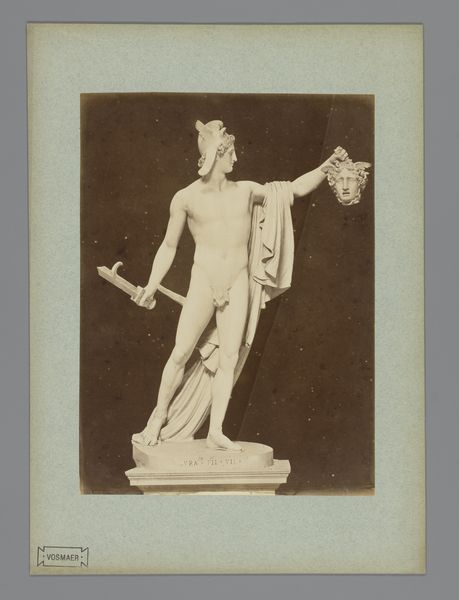

Sculptuur van Mars en Venus in de Galleria degli Uffizi te Florence, Italië 1857 - 1900

0:00

0:00

fratellialinari

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 246 mm, width 194 mm, height 355 mm, width 255 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a photograph taken sometime between 1857 and 1900 by Fratelli Alinari. It’s titled "Sculpture of Mars and Venus in the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence, Italy.” What's your immediate impression, Editor? Editor: Stately, but also oddly staged. It has that very 19th-century sepia tone and showcases two neoclassical sculptures together…almost as if they're posing for a portrait themselves. Curator: Exactly! What's interesting is the way the photographer uses the technology of photography to almost "re-animate" classical sculptures. These gods are removed from their original cultural context but re-presented for a modern audience, a phenomenon reflecting 19th-century Europe's obsession with the classical world. It begs the question of appropriation versus appreciation, doesn't it? Editor: Totally. And seeing Venus with her hand sort of possessively on Mars, almost gives it a touch of domesticity. Even divine love and war aren't immune, ha? This is a Gelatin Silver Print held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. Makes me think of contemporary artists who are in dialogue with their materials. Curator: The sculpture's portrayal of Mars, seemingly heroic, could be interpreted through a postcolonial lens. Here’s a figure representing military might rendered powerless under the soft, almost nurturing gaze of Venus. What does it say about gender and power in that historical context? Editor: Interesting point. The photograph then is not simply a static depiction of old sculptures, but it serves as a kind of layered visual text, revealing a lot about power dynamics within history, and the desire of 19th century colonialism to see beauty, morality, and even love, through an ancient and whitewashed view. It makes you question what kind of authority art historians, art critics and institutions have over history. It can all become rather dicey… Curator: Ultimately, it offers us the chance to unpack, to dismantle these narratives through critical engagement, challenging the idea of art history as fixed or neutral. Editor: Indeed, art can be so many things: a quiet document of art history, but also a dynamic playground.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.