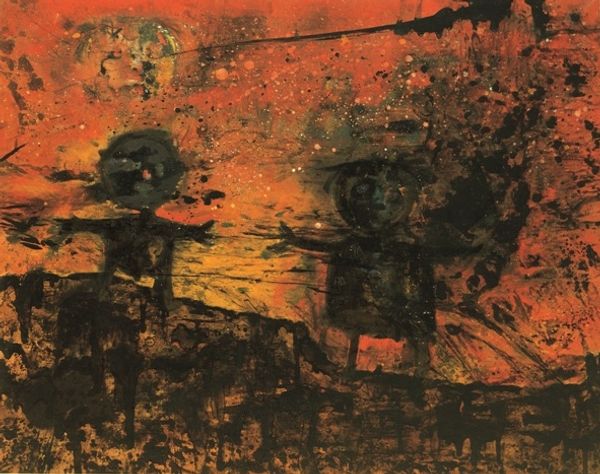

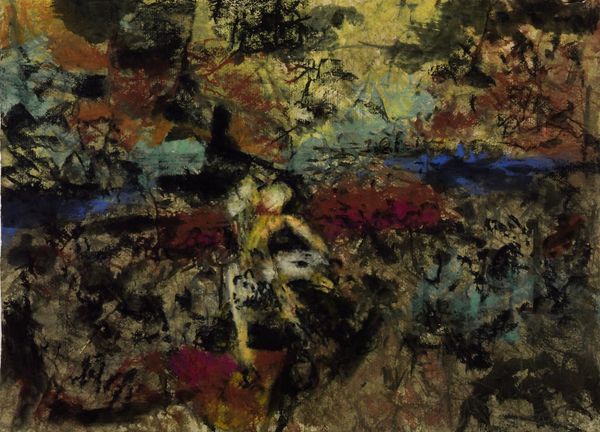

Dimensions: support: 632 x 970 mm frame: 642 x 981 x 22 mm

Copyright: © The estate of Denis A. Bowen | CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

Curator: What strikes me immediately is the sheer intensity of this work – such drama, and visual density too. Editor: Indeed, the composition seems to be vibrating with energy. This is Denis Bowen’s 'Crystallised Landscape,' currently held in the Tate Collections. Bowen, who lived from 1921 to 2006, has created an unsettling space. Curator: That title is interesting; it has an almost paradoxical quality. We tend to think of crystals as being precise and ordered, whereas here, the landscape feels volatile. Editor: Perhaps it's a metaphor for the geological forces at play, the immense pressure and heat required to form crystals, rendered here in paint. There’s a certain rawness. Curator: I agree. There's a primal quality to the use of red and black. It feels like peering into the earth's core, a symbolic space of transformation or even destruction. It’s a complex symbol. Editor: It reminds us that landscapes are never neutral; they are always imbued with cultural meanings and political histories, from colonial visions of terra nullius to contemporary debates about environmentalism. Curator: Yes, Bowen's landscape hints at the weight of human intervention upon it, transformed by its encounter with culture, memory and ideology. Editor: It offers a powerful, if disquieting, reflection on our relationship with the world around us.

Comments

tate 10 months ago

⋮

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/bowen-crystallised-landscape-t07840

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 10 months ago

⋮

Crystallised Landscape is one of a series of paintings by Bowen which is closely associated with the rise of Tachisme in Britain during the mid 1950s. This type of abstraction, characterised by dabs or splotches of colour (tache is the French word for spot or blotch), placed great value on the physical act of painting. For some painters the tache was theorised as an existential act, symbolising the freedom of the individual, for others, such as Bowen, it was a manifestation of the collective unconscious and the spiritual. His practice, which was steeped in quasi-Zen philosophy, involved the use of meditation to ‘empty his mind’ of thoughts. Once he had reached a state of ‘hyperconsciousness’, he would build up an image with rapid strokes, splashes and drips, using such unconventional materials as oil paint mixed with sand and household emulsions (Gaskin, p.44). Each picture was produced in one continuous session like Georges Mathieu’s (born 1921) abstract paintings. Bowen knew Mathieu, who had given a televised painting performance at the Institute of Contemporary Art in 1956 to mark the opening of his exhibition there.