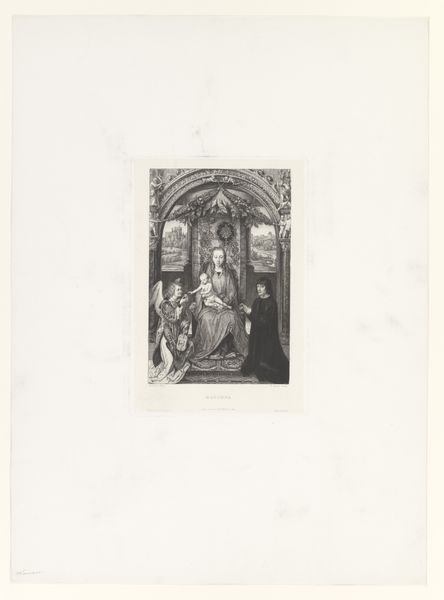

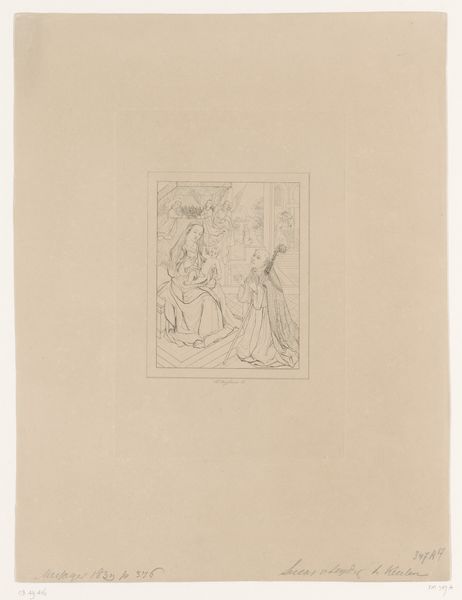

drawing, print, intaglio, paper, engraving

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

toned paper

#

medieval

# print

#

intaglio

#

old engraving style

#

etching

#

figuration

#

paper

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 275 mm, width 187 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Maria," an intaglio print made in 1841 by Charles Onghena. Editor: My first impression is… ethereal. There's a ghostly quality to the lines, making it feel like a vision or a memory surfacing. Curator: Exactly! The old engraving style lends a medieval feel, doesn't it? Onghena taps into a collective memory of religious iconography, specifically depictions of the Virgin Mary. The arched frame is instantly recognizable and anchors it to the visual vocabulary of faith. Editor: And situates it firmly within power structures of the 19th century that embraced historical religiosity to cement the bourgeois political order in post-Napoleonic Europe. The women kneeling, with the veiled faces and downturned eyes, they embody the ideals of feminine submission and piety of the era. Is this less about devotion and more about controlling women’s bodies and spirituality through institutionalised religion? Curator: Perhaps both are true at once? Look at the detail in the drapery. The folds aren't just fabric; they represent layers of meaning. The flowing lines could be interpreted as grace, but also concealment. It suggests the complexities of faith, both its comforting embrace and its potential for constraint. And then there's Mary herself – positioned as the singular ideal of womanhood and purity, which certainly raises a point of access to women as lesser others. Editor: That central figure does draw your eye. But doesn't the idealization present a distorted vision of lived female experiences? It places undue burden. Is this image perpetuating harmful social norms rather than simply reflecting them? Curator: It could certainly be read that way. Consider, though, how these images were consumed at the time. They weren’t merely passively observed but actively engaged with. People imbued these figures with personal meaning, sought solace and strength from them, and ultimately used the iconography to find empowerment as well. Editor: A fascinating idea! Curator: Indeed. Onghena’s piece, like all visual language, has many meanings, each one reflecting a particular place and time in society. Editor: It encourages us to reflect on how we continue to see women within systems of power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.