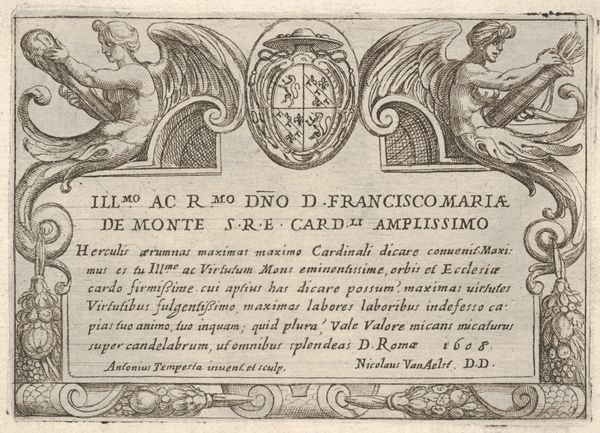

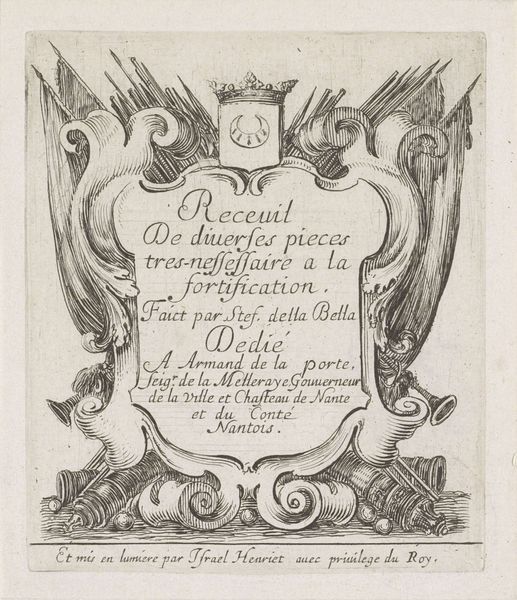

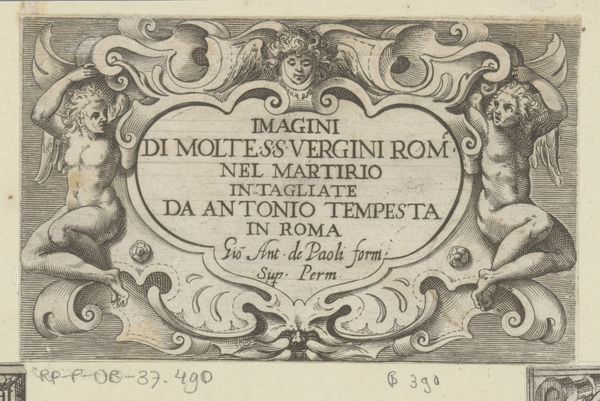

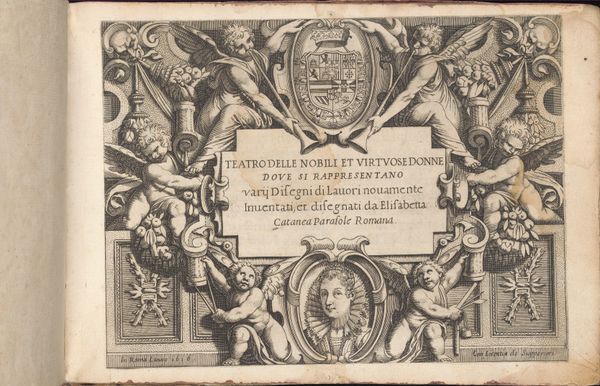

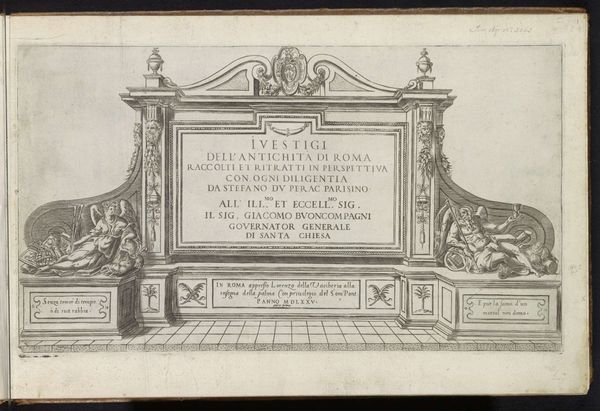

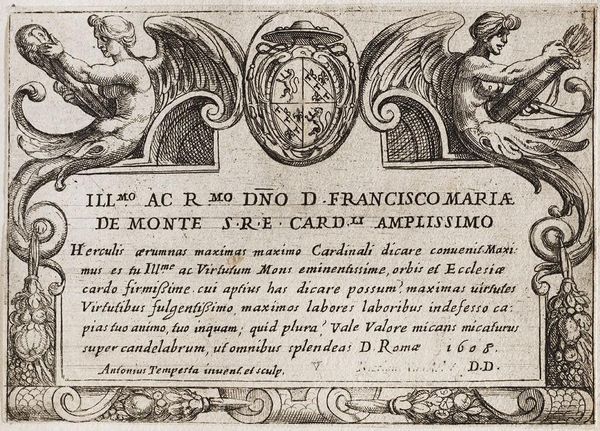

print, engraving

# print

#

old engraving style

#

geometric

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 114 mm, width 166 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

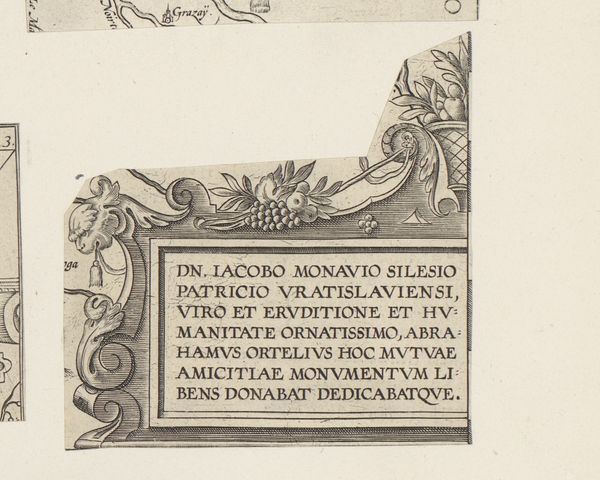

Curator: Abraham Ortelius' "Cartouche met leeuwenkoppen en maskers," dating from 1589. The engraving showcases a beautifully ornamented cartouche filled with text, framed by grotesque lion heads and masks, all overlaid on what appears to be a gridded map background. Editor: Immediately striking! It's incredibly formal, almost severe with its black and white lines and densely packed Latin text. But then those fantastical creatures disrupt any sense of perfect order. It’s a captivating tension between control and…well, chaos is too strong, perhaps wildness. Curator: It's fascinating to consider the engraving in its historical context. These kinds of elaborate cartouches weren’t simply decorative; they were integral to early mapmaking, serving as title blocks, dedications, and statements of authority. Ortelius, a royal geographer, is dedicating it to Nicolaao Roccoxio. Editor: Authority is certainly an impression it gives, but when considering its contemporary relevance, it speaks volumes about the power dynamics inherent in knowledge production, doesn't it? Maps were, and continue to be, instruments that codify worldviews, asserting control over both land and the narrative surrounding it. The almost aggressive heraldry and use of Latin reinforce that, signalling power only accessible to some. Curator: I agree. And thinking about the politics of imagery, it is relevant to remember Ortelius as a key figure of the Plantin-Moretus printing house. They used their cartographic output as powerful statements, helping establish Antwerp as a prominent cartographic center within a politically fraught climate. The careful choice of details contributed significantly to the creation of this carefully manufactured identity. Editor: That’s key – the identity, for whom? And what does it convey, besides prestige? There’s an almost baroque intensity of ornamentation at play that complicates its intended messages of scientific precision and power. The inclusion of mythological or fantastical elements subverts its rational purpose, maybe suggesting that scientific knowledge wasn’t quite so divorced from the fanciful imagination, at least in the public perception of the time. Curator: I see your point about the Baroque. The tension definitely evokes broader anxieties of the period regarding shifting notions of self and place. Thinking about art and its connection to the social and political climates reveals how it always mediates and affects historical understanding. Editor: Exactly. When engaging with artworks of this age, especially when they so pointedly declare something about their relationship with power, gender, and wealth, one is compelled to dissect not only their beauty but their deeper underlying message.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.