photogram, print, photography

#

16_19th-century

#

photogram

# print

#

war

#

landscape

#

photography

#

men

#

united-states

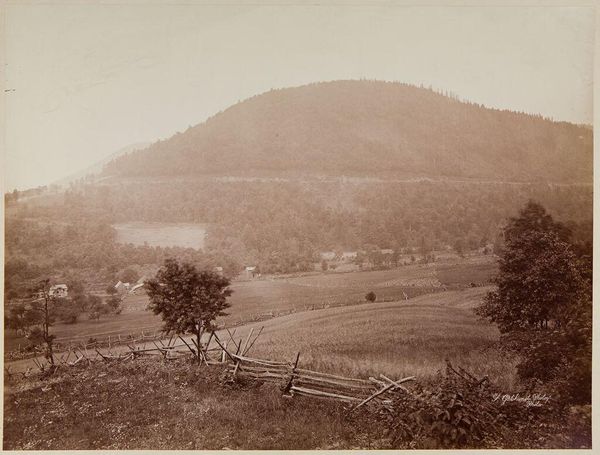

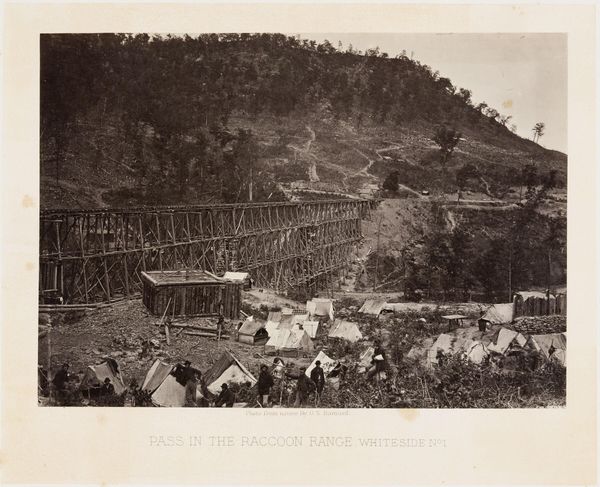

Dimensions: 25.5 × 35.7 cm (image/paper); 40.9 × 50.9 cm (album page)

Copyright: Public Domain

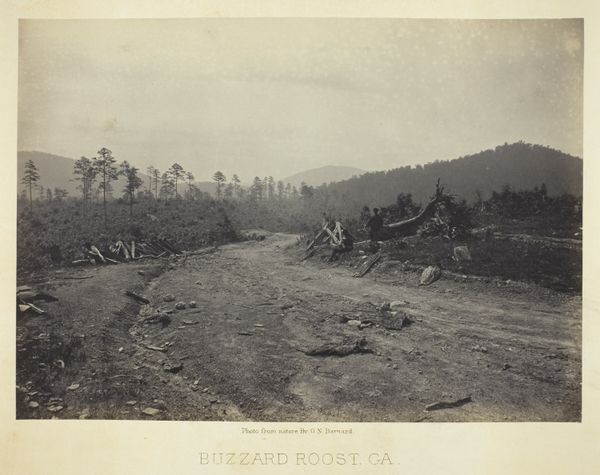

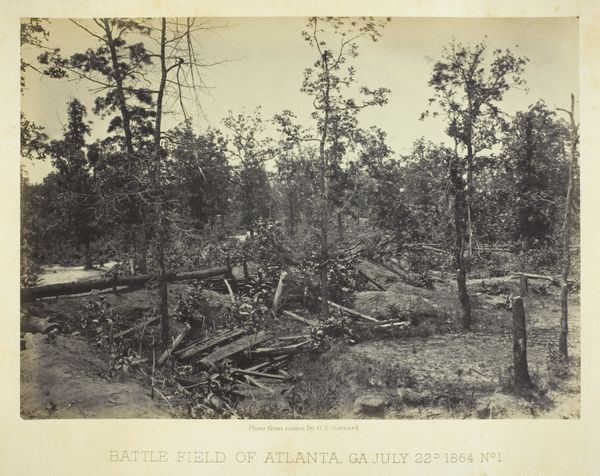

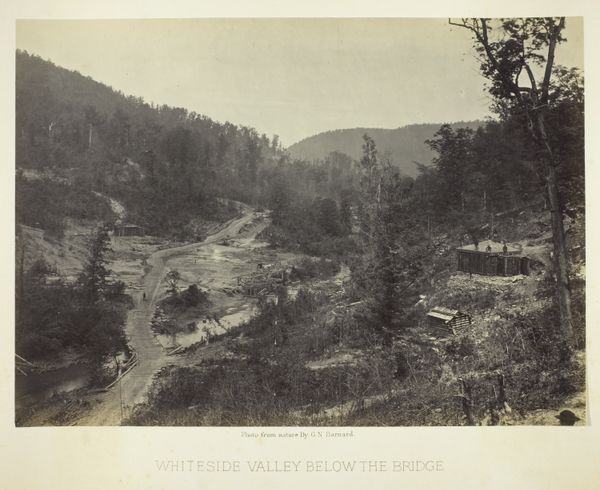

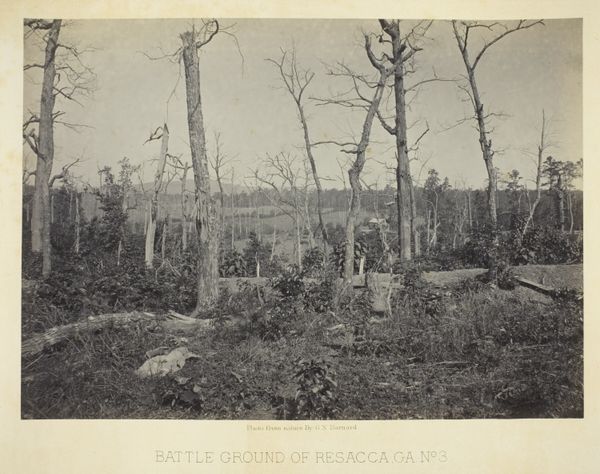

Curator: What immediately strikes me about this image is the eerie stillness. It's a landscape, yes, but so weighted with the *absence* of something terrible. Editor: Precisely. Here we have George N. Barnard’s "The Front of Kenesaw Mountain, GA," a photograph taken in 1866. It’s a print, created through a photogram process, and it depicts the aftermath of battle during the American Civil War. Notice how it freezes a moment of stark devastation, becoming a landscape of memory and loss in the post-bellum era. Curator: Memory and loss…that’s it. The scattered timber looks like bones, picked clean. And the quiet reinforces that haunting echo. What kind of stories were left unwritten because of all this? What happens after such brutal violence? It's enough to make a fella shiver on a summer’s day, wouldn't you say? Editor: Absolutely. Barnard, working often for the Union Army, captured not just the visible damage but also documented the infrastructure of war, influencing public sentiment regarding the conflict. There’s also, I think, a quiet critique embedded within; these photographs offer a haunting counternarrative to more glorified depictions of war. Curator: I suppose. It also offers the audience an almost sublime glimpse into our history. Knowing that the soldiers stood here, in that very spot. Makes your blood run cold to think that so many young men fell right here and never got the chance to have any perspective or to even feel a nice breeze or sunshine. Did Barnard do this intentionally, maybe trying to inspire others? Or was he merely documenting, like a surveyor making notes and calculating acres? Editor: The intent is complex, but given his extensive documentation of Civil War damage, there is a case for the conscious construction of a narrative focused on devastation and sacrifice, one that challenged idealized or celebratory wartime images circulating at the time. We can even connect these efforts, made primarily for the victors to shape what happened next, as propaganda tools. What this imagery was in fact, saying, 'never again'. Curator: You know, I've thought about the title more too; this IS the front line! Right here. Right where the audience is! Very direct. So here it is... Look at it! And don't forget. Editor: It’s a compelling way to understand how art engages with national narratives and collective memory. Curator: Very powerful... thank you. Editor: Indeed, a poignant encounter.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.