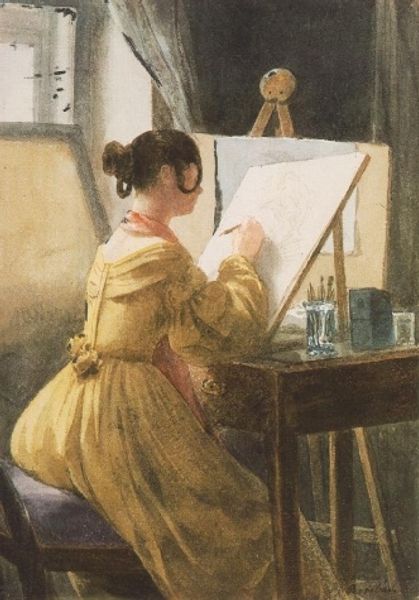

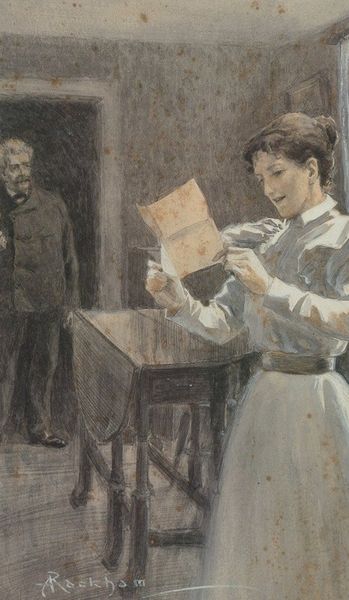

Kramsky, who writes a portrait of his daughter, Sofia Ivanovna Archaeology from marriage Juncker 1884

0:00

0:00

Copyright: Public domain

Editor: So, we're looking at "Kramsky, who writes a portrait of his daughter, Sofia Ivanovna Archaeology from marriage Juncker," painted by Ivan Kramskoy in 1884. It’s an oil painting currently hanging in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. There’s a quiet intimacy to the scene, seeing an artist portraying his daughter. How does the historical context shape your understanding of this particular work? Curator: It's interesting that you note the intimacy. Consider the role portraiture played in 19th-century Russian society. It was not just about capturing likeness; it was about conveying social status and personal character. Kramskoy, as a key figure in the Peredvizhniki movement, aimed to depict real life and challenge the academic art establishment. Do you think this portrait reflects that ethos, or does the subject – his daughter – perhaps shift his approach? Editor: I think there’s an element of both. There’s a softness and tenderness that feels different from his more overtly social commentaries. Maybe it's the gaze; it feels less posed and more genuine. But even that ‘realness’ must be a choice, right? A carefully constructed image? Curator: Precisely. Kramskoy’s artistic choices, even in depicting his daughter, are still choices shaped by the socio-political environment. The painting subtly positions him, the artist-intellectual, within the emerging Russian cultural landscape. By showing his act of painting, he's portraying not only Sofia, but also defining the artist’s role within society. How does this "artist-at-work" composition affect our perception of Kramskoy and his daughter, individually and as part of Russian culture? Editor: That's fascinating. It makes me see the painting as less of a personal moment and more as a deliberate statement about art-making itself. He's inserting himself into the narrative, almost as a champion of a new kind of representation. Curator: And it tells us much about how the burgeoning middle class viewed itself at that time and wanted to be viewed, what symbols they deemed necessary, what gestures appropriate for visual dissemination to their peers, right? Food for thought about social context. Editor: Definitely. This gives me a whole new perspective. Thanks.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.