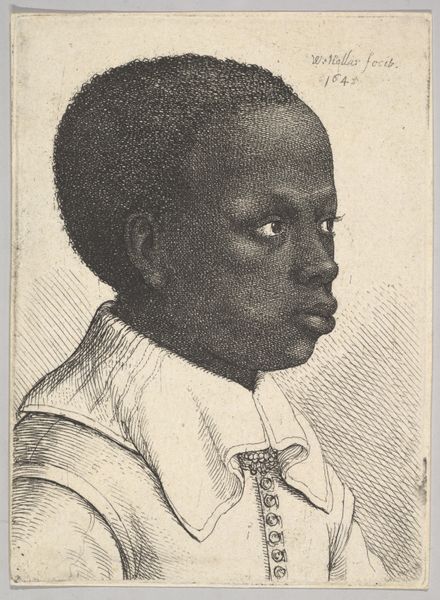

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

charcoal drawing

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

#

portrait art

Dimensions: height 274 mm, width 218 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

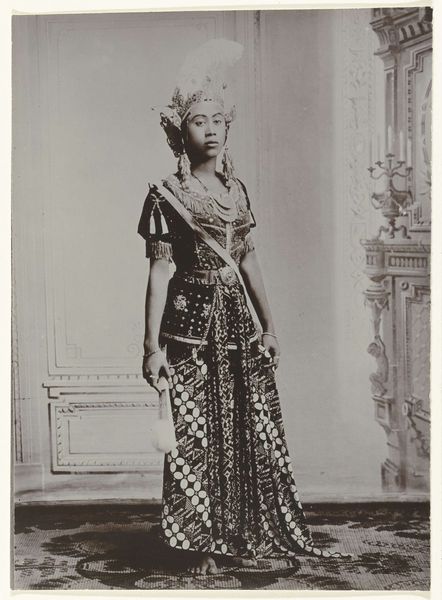

Curator: Before us is "Portrait of a Black Woman with Pearl Necklace," an engraving by Cornelis van Dalen the Younger, dating roughly from 1648 to 1664. It’s part of the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: It strikes me as… elegant, but undeniably unsettling. The sitter’s direct gaze, framed by pearls and fine fabrics, creates a feeling of both accessibility and distance. What’s the context here? Curator: Exactly. The context is paramount. Consider the Dutch Golden Age, its global trade networks and colonial expansion, particularly the transatlantic slave trade. This image enters a complicated representational history. The woman's adornments, while seemingly celebratory, exist within that economy of exploitation and consumption. We have to interrogate whose gaze this portrait serves and at whose expense that vision is constructed. Editor: Absolutely. The means of production are key. This wasn't oil on canvas, destined for a wealthy patron. It’s an engraving, meant to be reproduced, consumed as part of a print market increasingly interested in portraying diverse peoples, often in very specific and charged ways. Curator: Precisely. The material—the very act of replicating this image—speaks to the societal norms and attitudes of the time. The printing and mass distribution point to how difference was perceived and circulated. What does it signify when images like this become part of a culture deeply implicated in systemic oppression? Editor: It's fascinating how the material choice underscores the commercial and, perhaps, exploitative dimension of this portrayal. A painting, perhaps, signals status of the sitter, but the print signals trade, circulation, demand, almost like an early form of ethnological documentation—packaged for consumption. Curator: It's a convergence of artistic skill, societal expectation, and power dynamics, creating an image that’s far more complex than it appears. Her gaze challenges us to look critically at our own historical consciousness. Editor: Indeed. Examining the details of the craft pulls back the curtain on a web of intertwined histories: art, commerce, labor, and representation all bundled into this small printed square. Curator: Thinking about her gaze intersecting with feminist thought pushes us to reimagine how colonial portraits have historically formed individual identities and shaped historical realities for Black women. Editor: Thinking of how the pearls are a product of the natural world and yet reconfigured into symbols of status forces an acknowledgement of natural resources turned into instruments of capital.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.