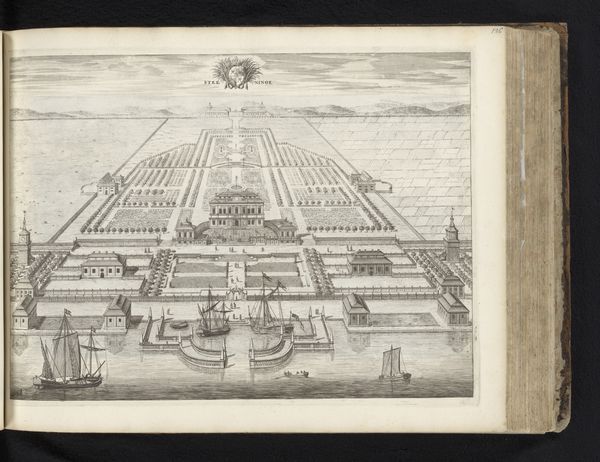

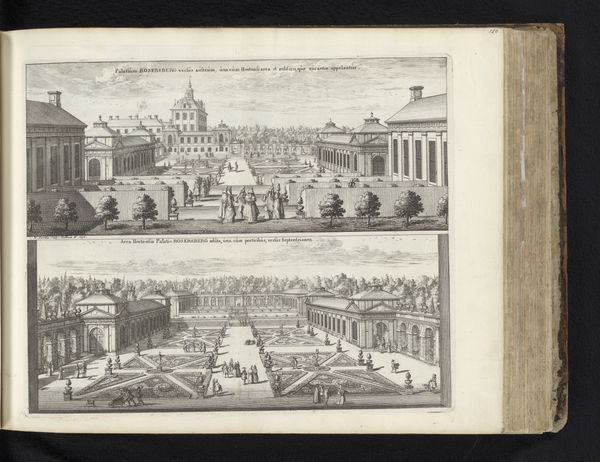

print, engraving

#

garden

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 266 mm, width 383 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Today we are observing Willem Swidde’s “View of the Östanå Mansion and Garden from the South,” a baroque cityscape dating back to 1694. It's an engraving showcasing landscape elements that were characteristic for the epoch. Editor: It looks like a blueprint for absolute power. So meticulously organized, with such an assertive control over nature. All lines, precise angles, clearly hierarchical… the image breathes of privilege, and I dare say, of suppression. Curator: Precisely. See how the design emphasizes perspective? The layout leads the eye from the waterfront directly to the mansion. Swidde uses contrasting textures to create depth. Consider also the balance achieved with the heraldic symbols—symmetrical and perfectly spaced in the top register. Editor: It's all part of projecting dominance. Gardens weren’t simply places of beauty but powerful symbols. This isn’t merely landscape; it’s a declaration of land ownership and social stature. It speaks volumes about how elites literally shaped the world to reflect their self-image. What labor, what resources it took to maintain such artificial constructs… Curator: True, but we shouldn't dismiss Swidde's skill. The intricate linework creates an almost photographic level of detail. Note the depiction of human figures within the garden: they contribute to the scale, enhancing the overall sense of grandeur. It really emphasizes the impressive precision and clarity. Editor: A clarity built on inequality! Those tiny figures likely represent servants and laborers maintaining this display. This visual culture reinforces power structures, conditioning viewers to accept such hierarchies as natural or beautiful, as opposed to a blatant exercise of control. How can we admire beauty when it arises from exploitation? Curator: I recognize that tension, but isn’t part of our role also to appreciate technical execution and historical context? Swidde’s engraving, after all, gives us a glimpse into how these estates wanted to be seen, and helps us to consider these themes. Editor: Absolutely, engaging with such visuals critically means we're challenging these projected narratives. It is an invitation to think deeply about what costs come with manufactured idylls and curated experiences. I look away with renewed consciousness about social architecture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.