Dimensions: height 116 mm, width 162 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

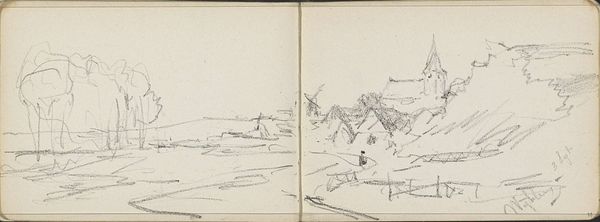

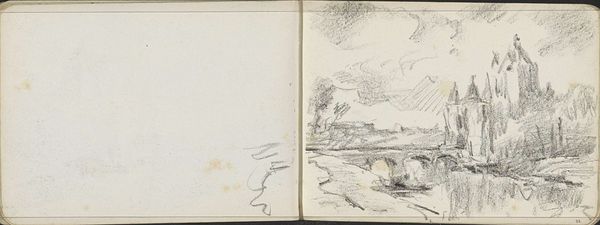

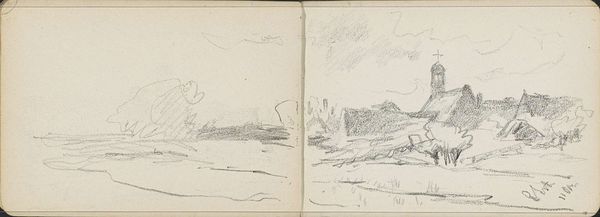

Curator: Here we have Willem Cornelis Rip's "Kerk van Persingen," a pencil drawing from somewhere between 1905 and 1907. Editor: My first impression is one of quiet solitude. It is executed simply, almost tentatively. There's a muted atmosphere; like observing a memory gently surfacing. Curator: I think your reaction speaks to Rip's place within the evolving landscape genre, moving from earlier Romantic idealizations to a kind of quiet, impressionistic realism. Consider how societal shifts around religion, secularism, and evolving notions of community play out here. Rip gives us not a grand symbol of faith but a modest, almost demure church in its landscape. Editor: True, but the framing is intriguing! Why the starkly blank page next to the rendering of the church? Is it implying the fading of a certain cultural centrality of religious institutions, allowing room for the secular landscape of society to grow into? The juxtaposition feels pointed. Curator: It may speak more to Rip’s technique, showing two different landscape studies within one opening spread. It’s more practical than polemical. The church grounds this work within a particularly Dutch tradition of landscape art. There is something quite poignant about the presence of the church, viewed not as a dominating structure but nestled into the natural world. Editor: Agreed. Think, also, of the symbolism. Churches have often represented a patriarchal system and a power structure in art history. But here it feels humanized and somewhat diminished in importance against the broad horizon line behind it. Rip allows space for challenging conventional readings. Is there perhaps an invitation here to re-evaluate those older power dynamics? Curator: Maybe, maybe not. I’m inclined to think we risk imposing contemporary anxieties onto earlier concerns here. Rip was clearly more interested in faithfully rendering what was directly in front of him with a soft, personal touch. Editor: Still, the artist's intention isn’t the only important thing! The socio-historical lens allows us to consider not only what was intended, but also what the artwork can now reveal about past cultural dialogues as our society develops over time. Curator: I suppose our dialogue reflects Rip’s work then: a convergence of observational art, socio-historic understanding, and a little present-day reflection. Editor: Exactly, and perhaps that space between the church and the land represents the beginning of the artist challenging social norms that surround the function of art and of religion itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.