drawing, print

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

Dimensions: Sheet: 6 5/16 x 5 3/8 in. (16 x 13.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

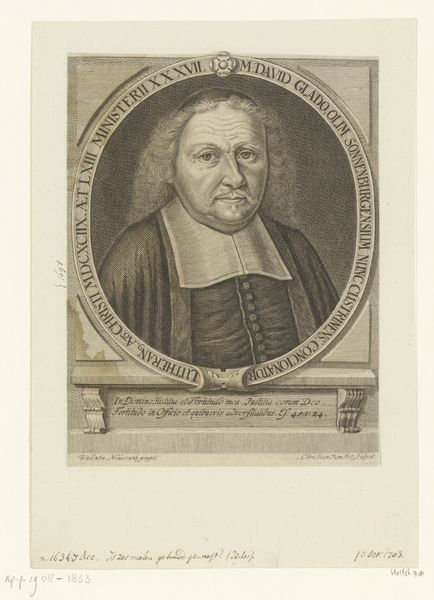

Curator: Here we have Richard Livesay's "The Parson's Head," dating to 1788, residing here at The Met. What's grabbing your eye about it? Editor: It's austere but immediately draws you in. The circular frame isolates the parson, focusing all the attention on his…well, his very lived-in face, captured through very precise engraving or etching I suppose. There is this tangible presence and almost a slightly offputting directness. Curator: Indeed. It’s fascinating how Livesay captures the details in a Neoclassical style, but departs in creating the sense of intimacy with the figure. You notice the medium, right? A print; engravings and etchings were a medium capable of broader distribution. It allows for wide dissemination of portraits – of cultural figures, whether lauded or lampooned, or of no historical importance otherwise. Editor: Exactly. These aren’t brushstrokes of oil paint designed for a wealthy patron’s private viewing room. A printed portrait suggests a very different purpose and audience. The relative ease of reproduction allowed more common individuals to attain "immortality". This opens all manner of interesting discussions of materiality in class and social meaning. It's also hard not to consider that his robes lack ostentation - perhaps it signals modesty but perhaps not the success of his career? Curator: That’s very insightful. Also considering who is Livesay working for. While Livesay trained with Benjamin West, he had already moved toward a radical political stance which is further reinforced when he is associated with people like Thomas Paine. The “Parson’s Head” then speaks less about individual merit, and instead operates as a more generalizable observation. It engages with questions of clerical authority and social standing as social commentaries in revolutionary times. Editor: It certainly provides plenty to chew on! Even simply considering the skill in capturing such life from such limited materials sparks fascination, but the greater context only expands the potential meanings and ways to examine this piece. Curator: Agreed. Looking closer at this piece provides a fascinating cross-section of artistic technique, social critique, and the burgeoning culture of print media in the late 18th century. Editor: Indeed, something in which the parson, and his peers, may have had an interest too as he would have lived in a society governed, in no small part, by the products and consumption of printed media.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.