Dimensions: 6 × 8 11/16 in. (15.2 × 22.1 cm) (image)9 11/16 × 12 13/16 in. (24.6 × 32.5 cm) (sheet)17 9/16 × 21 1/2 × 1 1/8 in. (44.6 × 54.6 × 2.9 cm) (outer frame)

Copyright: Public Domain

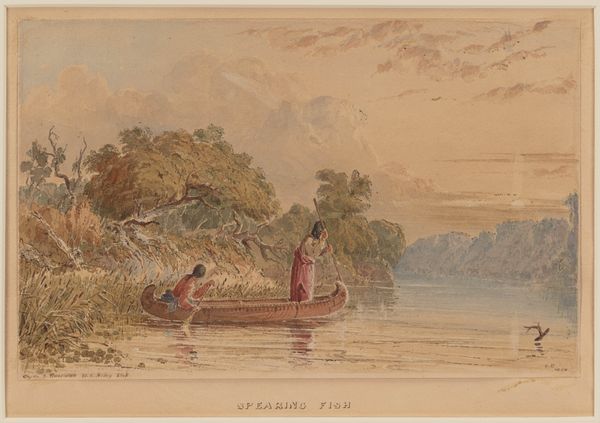

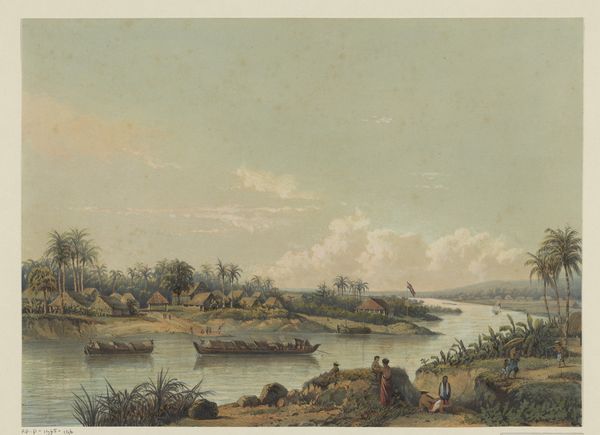

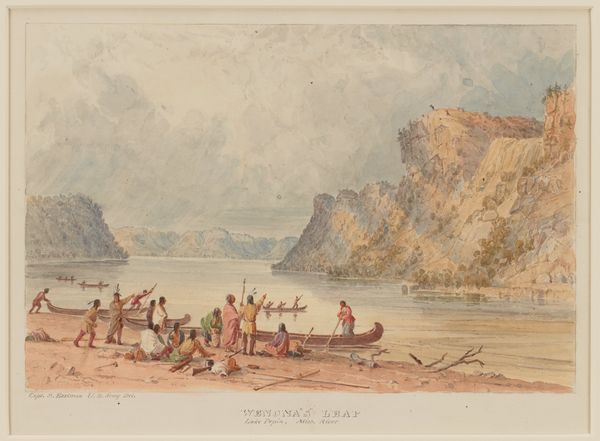

Curator: This is Seth Eastman’s watercolor entitled "Itasca Lake," made sometime between 1849 and 1855. The Minneapolis Institute of Art is fortunate to have it in their collection. Editor: It feels like peering through a time portal! A gentle palette of earthy pinks and mossy greens creates this tranquil landscape. Is that a little encampment on the shore? Curator: Yes. Eastman, while serving as a U.S. Army officer, documented Native American life and landscapes, particularly in the areas he was stationed. The image reflects not just the landscape but also the interactions between different cultures at that time. Editor: You can certainly feel a sense of...observation, perhaps? Almost as if the scene is being carefully documented. Look at those figures in the canoes – there's a narrative unfolding, but we're just catching a fleeting moment. It's romantic but detached. Curator: The detachment stems from Eastman's position. He was commissioned to record what he saw, aligning with broader governmental and scientific interests in documenting and often, claiming, territories and populations. His work walks a tightrope between ethnographic record and Romantic landscape painting. Editor: I'm struck by the light, the soft gradations across the water. Despite its historical context, which does give me pause, there's something undeniably beautiful in how he captures the stillness of the lake. It makes you wonder about the quiet hum of nature that existed before... all of *this*. Curator: Eastman’s artistic style blended elements of academic art with Romanticism, reflecting an era where there was growing interest in, and anxieties about, wilderness, expansion, and encounters with Native populations. His work contributes significantly to understanding attitudes in antebellum America, and the politics embedded in landscape imagery. Editor: Looking at it now, with all this in mind, it's more unsettling than serene. Makes you rethink every "peaceful" vista, doesn't it? Curator: Absolutely. It compels us to question whose perspective informs the stories that become "history." Editor: Indeed. "Itasca Lake" initially charmed with its pastoral aesthetic, but now whispers about how landscapes are never innocent, always loaded with a past we must consider.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Minnesota schoolchildren know Henry Rowe Schoolcraft as the explorer who in 1832 confirmed the source of the Mississippi River, and named it Lake Itasca. They also know that Itasca derives from the Latin for “truth” and “head”: veritas and caput. They also can thank Schoolcraft for finding our first state park, which the spot became in 1891. This watercolor, based on a Schoolcraft sketch, depicts the moment after his expedition arrived. One of 35 works on paper by Seth Eastman in Mia’s collection, the painting was the basis for an illustration in Schoolcraft’s massive "Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States" (Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co., 1851-57).

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.