photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 65 mm, width 117 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

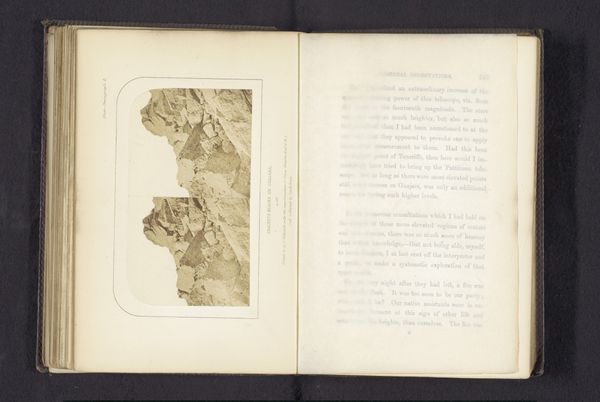

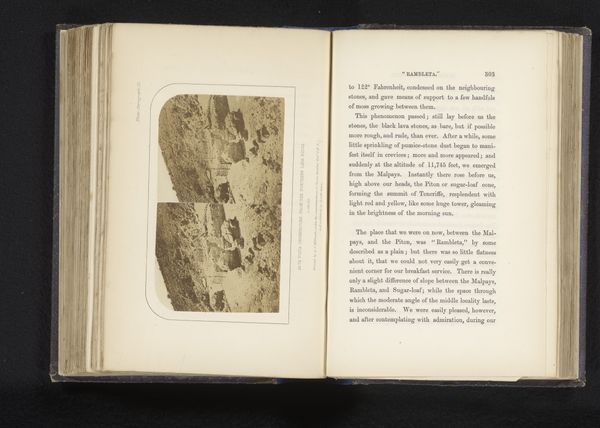

Curator: This gelatin silver print, entitled "Gezicht op de krater bij de berg Guajara", was captured between 1856 and 1858 by Charles Piazzi Smyth. Looking at it now, one might immediately notice the seemingly lunar-like desolation. Editor: Absolutely. The stark, monochrome tones, combined with the sharp, angular forms of the volcanic rock, evoke a sense of profound solitude and geological drama. The high contrast gives it a distinctly raw, almost primordial feel. Curator: The image documents the landscape, yet it's essential to recognize that Piazzi Smyth made these photographs during an expedition to Tenerife aimed at proving the suitability of high-altitude locations for astronomical observation. The social context surrounding this expedition and Smyth’s goals are critical. We might consider his biases as a Victorian scientist as shaping this depiction of the landscape as an “objective” subject for scientific study. Editor: True, but also let's not diminish the way Smyth harnesses the materiality of gelatin silver to create a meticulous study in texture and form. The layering of tones from the white of the highlights to the velvety shadows is particularly effective in rendering the three-dimensional volume of the volcanic structures. The artist's commitment to symmetry through the doubled print amplifies a scientific attitude as well as offers a novel and affecting stereoscopic experience for the viewer. Curator: I'd also emphasize how landscapes in the 19th century, particularly those depicting remote or seemingly untouched terrains, were often utilized to promote ideologies of expansion and domination. Consider how representations of nature might support colonialism or the dispossession of Indigenous peoples. While we have no indigenous subjects present in this frame, the romanticisation of untouched landscapes becomes an interesting area for discussion. Editor: Fair enough, but focusing solely on historical or political contexts can eclipse our capacity to see it formally. Before you can deconstruct any ideological framework, it’s essential to apprehend the picture's intrinsic components. Without that, our deconstruction risks becoming superficial, reducing the artwork to a mere vehicle for extraneous arguments. Curator: Well said. Perhaps we find ourselves suspended in a productive tension, both acknowledging the artifice and considering its impact on historical discourse. Editor: Indeed, each approach—contextual and formal—lends something to a greater, richer understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.