drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

oil painting

#

ink

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: sheet: 9.4 x 10.9 cm (3 11/16 x 4 5/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

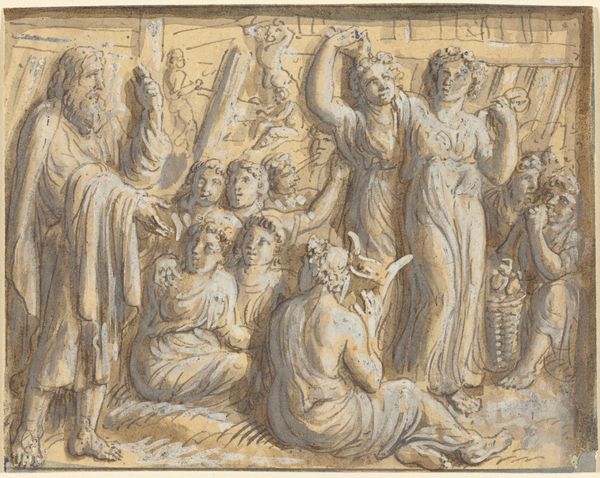

Editor: So, here we have Luigi Ademollo’s drawing, “Moses and the Brazen Serpent,” rendered in ink on paper. The drama! The figures contort and writhe – it’s quite a scene of chaos and desperation. What exactly is happening here? Curator: Well, at face value, it illustrates a biblical story, a common subject for art through the ages, of course. But consider how such a dramatic depiction might function in a specific social context. How does visualizing this particular moment in religious history reinforce certain power structures? Editor: Power structures? Could you expand on that? Curator: Certainly. Think about it: Ademollo presents Moses as this powerful intercessor, holding aloft the cure for the plague. The people are utterly dependent, writhing in pain, eyes fixed on him. The imagery promotes the idea of hierarchical leadership, right? God, Moses, the people. Who would commission such an image, and what purpose might it serve beyond simple illustration? Editor: Maybe someone seeking to reinforce their own authority or promote the church's? This could almost be propaganda. Curator: Precisely. It’s crucial to remember that artistic choices are rarely neutral. The depiction of suffering, salvation, and leadership within a religious framework serves particular ideological ends. Note also the visual language – the echoes of classical sculpture, imbuing the scene with a sense of timeless authority. Editor: That makes total sense. It’s not just about the story; it’s about how the story is being told, and *why*. Curator: Exactly! And how that ‘why’ is intrinsically tied to the artwork’s position in society. This really opens my eyes to the social and cultural contexts of art. Editor: Mine too! I'll definitely consider the public role of art, especially when it portrays a moment in history, going forward.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.