print, woodblock-print

#

portrait

# print

#

asian-art

#

caricature

#

ukiyo-e

#

woodblock-print

#

orientalism

Dimensions: height 374 mm, width 247 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

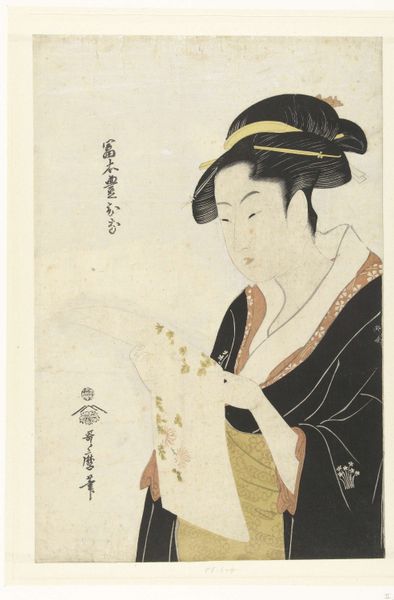

Curator: Before us we have Kitagawa Utamaro's "Brief lezende vrouw," or "Woman Reading a Letter," created sometime between 1793 and 1797. This striking ukiyo-e woodblock print is part of the Rijksmuseum's collection. Editor: It’s incredible how Utamaro captures a sense of anticipation here. The composition draws my eye immediately to the rolled-up letter, emphasizing its importance through the way it is being handled by the figure. The neutral tones emphasize the subject’s delicate expression and suggest an inward focus. Curator: Absolutely. Considering the context, we can think about how such prints served as a crucial medium for disseminating images and ideas across Edo-period society. Here, the letter—likely a personal correspondence—takes on a more charged significance, connecting to debates on women's literacy and societal roles within the era. Editor: Precisely. Utamaro masterfully arranges the elements. Note the use of line: the soft curves of the woman's posture against the more geometric patterning of her garment create a compelling visual rhythm that also speaks to her inner concentration. It’s almost like a dance on the picture plane. Curator: Indeed, but this "dance," as you call it, isn’t divorced from the historical narrative. Examining class and gender, we see how Utamaro simultaneously caters to and critiques societal expectations. The very act of depicting a woman engaged in reading was a statement, albeit one open to diverse readings at the time and today. Editor: I agree that Utamaro’s choices invite questions beyond simple aesthetics. I’d argue that its beauty relies upon the deliberate juxtaposition of elements – line, form, color and texture – creating an art that exists through these structural relationships. Curator: The historical lens, however, encourages a more nuanced perspective. "Brief lezende vrouw" becomes more than just an artwork; it acts as a mirror, reflecting the multifaceted identities and social dynamics that shaped 18th-century Japan. Editor: And so, even if we begin by looking at color and form, Utamaro’s technique has ensured an experience of contemplation that stays with us long after our analysis. Curator: By bridging the past with the present, we see how an ukiyo-e print continues to inspire dialogue—challenging, provoking, and above all, reminding us of the powerful connections between art and life.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.