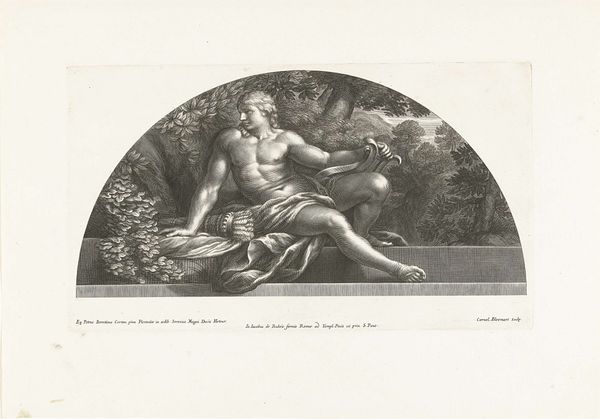

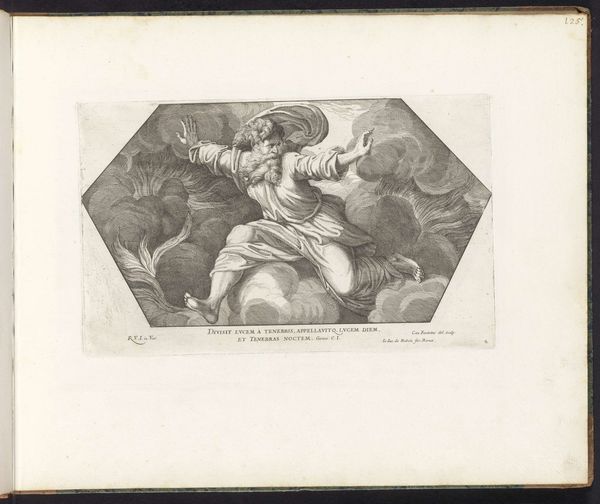

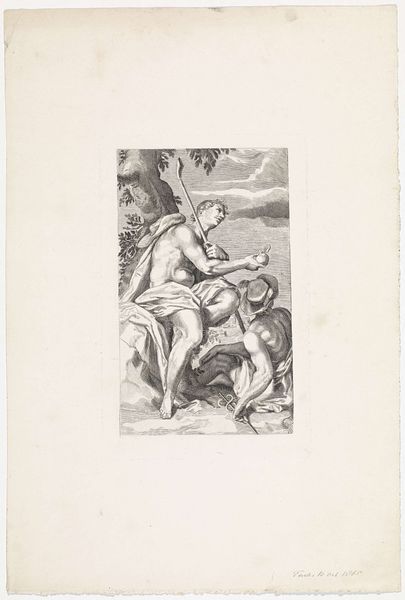

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

history-painting

#

graphite

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 200 mm, width 343 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is "Vulcanus," an engraving by Cornelis Bloemaert, created sometime between 1637 and 1692. It’s currently held at the Rijksmuseum. What strikes me is how pensive Vulcan seems, almost bored amidst the tools of his trade. What do you see in this piece? Curator: The engraving really foregrounds the means of production, doesn't it? Bloemaert’s skilled use of line to depict textures – the rough stone, the polished metal – directs our attention to the labor involved. It makes me consider the status of printmaking itself, as both a skilled craft and a method for disseminating imagery and ideas to a wider audience. What sort of workshops produced prints like this? Were they challenging the accepted hierarchies of labor in the art world? Editor: That’s fascinating! I hadn’t thought about it that way. It makes me wonder about the intended audience for this print. Was it meant to elevate the status of craft, or was it simply a reproduction of a more prestigious artwork, like a painting? Curator: Precisely. And think about the classical subject matter: Vulcan, the god of the forge. It's high art referencing a craftsman! The act of creating the print then becomes another layer in this complex relationship. The engraver is almost performing a type of skilled labor mirroring the original artisan's work that Vulcan represents. What does this interplay of "high" and "low" art forms tell us about the period? Editor: So, it’s about challenging our understanding of value, not just the depiction of Vulcan, but also the very act of creating this engraving. I’ll never look at prints the same way! Curator: Indeed. And by exploring the materiality of the print – the paper, the ink, the engraving tools – we start to see art history not just as a succession of masterpieces, but as a history of making and doing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.