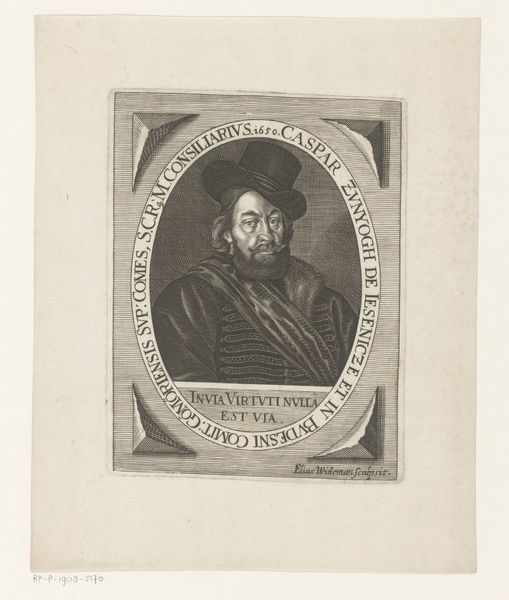

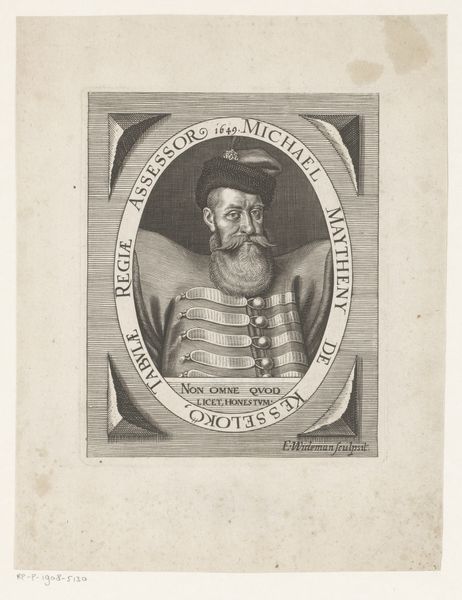

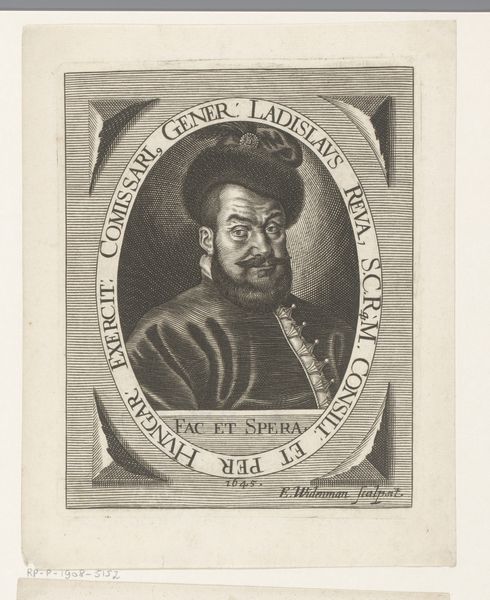

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 143 mm, width 114 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. Today we’re observing a Baroque portrait from 1647, "Portret van János Kéry," created by Elias Widemann. It's an engraving, a fascinating example of period portraiture now held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My initial reaction? Strikingly detailed. I am immediately drawn to the textural qualities, especially the rendering of the fur trim and the minute lines creating the impression of volume. One can tell there was significant labour and skill involved. Curator: Absolutely. Widemann operated in a world deeply shaped by patronage and the political symbolism attached to portraiture. Notice how János Kéry is framed with Latin inscriptions – "PAX OPTIMA RERVM" or "Peace is the Best of Things." This was crafted in a society of hierarchies; conveying not just likeness, but status, affiliation and Kéry's role as the Royal Crown Guard of Hungary. Editor: That social dimension resonates when we examine the means of production. Engraving allowed for relatively easy reproduction, disseminating this image and thus Kéry's persona and influence beyond a singular, unique painting, almost as propaganda. But consider the economics: what did this proliferation mean for the engraver’s livelihood versus Kery’s image? Curator: An astute point. Printmaking did democratize images to an extent, allowing for wider dissemination, yet power dynamics are baked into the system. Also think about the reception - for contemporary viewers, the formal pose and symbols would immediately signal authority. It spoke to notions of Hungarian sovereignty, the strength of their aristocracy within larger European conflicts. Editor: Yes, but also of control through representation. The very act of meticulously reproducing Kéry's likeness—the almost industrial, relentless work—highlights the power someone, like Widemann, invested in fixing a material, viewable, copy of authority through material means. What responsibilities came with those reproductions? Curator: A good point to raise for discussion. The question remains open about an artist's agency within political projects like that of János Kéry. Considering Widemann, were there expectations he had to deliver to align the work within set protocols, which he successfully did to contribute towards János' and, more so, the King's brand of control and prestige? Editor: Reflecting on our perspectives here, this single engraving becomes a site where cultural narrative and tangible craftsmanship meet—a mirror for revealing much about social standing in Baroque society. Curator: Indeed, this piece makes us look deeper than a simple portrayal of a Hungarian royal official; to question the socio-political contexts and their long-lasting echoes in both materials and historical understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.