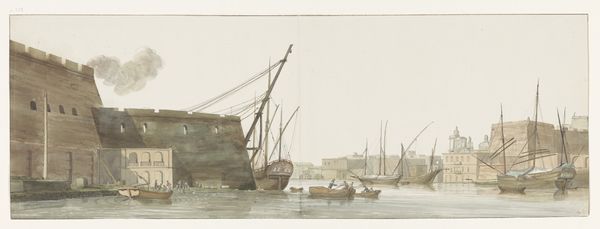

Fishing boats in Rye Harbour, with a windmill in the distance 1850 - 1855

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: 248 mm (height) x 347 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: Ah, this is a gentle watercolor landscape from between 1850 and 1855, titled "Fishing boats in Rye Harbour, with a windmill in the distance." Editor: It feels so melancholy. The grounded fishing boat looms large in the foreground; you can almost smell the brine and rot. There’s such a sense of abandoned industry here. Curator: Absolutely. Look closely at the materiality; watercolor perfectly captures the dampness, the ethereal quality of light over water. Consider the labor embedded in those boats, the precariousness of the fishing industry. The Romantic sensibility idealized the rural and agrarian, yet here we sense its inherent vulnerabilities. Editor: The location – Rye Harbour – is also key. This would have been a working port. The windmill hints at another industry tied to natural forces, wind power literally driving production, though probably at the time threatened by new modes of production. It's romantic but also quietly tragic, pregnant with a premonition about lost labour. Curator: I'm also interested in the visual dialogue between the large derelict boat and the operating one closer to the shore, filled with workers and heading elsewhere. What can these types of maritime narratives teach us about class mobility in Britain and how one survives when their boat runs ashore? Editor: We can dig further by acknowledging the impact and transformation of resources such as oak and tar during ship making to understand how essential they are to society as a whole, and what would ultimately become obsolete as new industrial developments were adapted. Curator: Considering the Romanticism in this work, it could be useful to reflect how these social narratives fit into notions of industrial and agricultural production that were prevalent throughout that era. Editor: Yes, and by highlighting the tangible elements - the timber, the sails, even the very watercolor paint - we see art entangled in material and social systems. It’s not just a pretty picture; it’s a historical artifact laden with stories. Curator: Precisely. The boats and harbour symbolize broader political, gender, and social realities experienced by all those within the British working class. Editor: It pulls us away from aesthetic appreciation to consider how economic realities truly affect an artwork and our own lives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.