print, etching

#

dutch-golden-age

#

ship

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

archive photography

#

orientalism

#

cityscape

Dimensions: height 345 mm, width 510 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

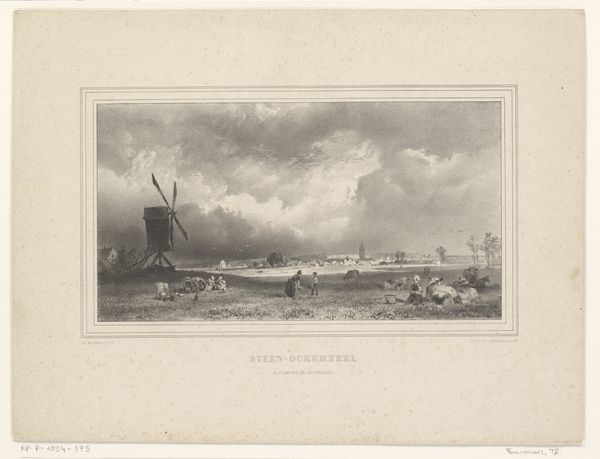

Curator: Welcome to the Rijksmuseum. Today, we're looking at "Aanlegplaats voor sloepen in Batavia" by Paulus Lauters, created between 1843 and 1845. It's an etching that offers a detailed view of a boat landing in Batavia, now Jakarta. Editor: My first impression is of a very ordered and tranquil scene, almost deceptively peaceful. The grey tones, despite being necessary for the print medium, lend a certain serenity to the waterside. Curator: Indeed. Lauters produced this print within the context of Dutch Orientalism, reflecting the colonial gaze on the East Indies. Etchings like this were crucial in shaping European perceptions of these distant lands, often romanticizing or idealizing them. Editor: I think the romanticization speaks to the function of this piece: a soft, accessible portrait for European viewers of Dutch economic interests abroad. Who exactly are we seeing here in this scene and what does it mean to present them so nonchalantly in this "tranquil" moment? Curator: You make a vital point. The seemingly innocuous scene is charged with the power dynamics of colonialism. The native figures, presented as diminutive and passive, are juxtaposed against the implied authority of the Dutch presence. Their likenesses served a documentary purpose to solidify European racial "science" efforts at the time, creating a permanent record. Editor: Right, the everyday becomes a site of ideological contestation. The very act of documenting these landscapes and their inhabitants serves to legitimize colonial control, rendering them as passive subjects within a European narrative. Curator: And the detail in the ships, the buildings, and the people tells us much about the infrastructure of trade and governance in the Dutch East Indies at that time. Prints like these were also circulated as commodities, reinforcing the Dutch dominance in publishing and visual culture. Editor: Looking at this now, knowing its history and purpose, that so-called tranquility I first noted gives me a very different feeling. It now feels unsettling and deeply implicated in power. The quiet suggests a subtle enforcement, doesn't it? Curator: Precisely. It reveals how even seemingly neutral depictions were, in fact, instrumental in maintaining and propagating the colonial project. Editor: Thank you, that offers such necessary critical context, enriching our understanding of this piece and prompting reflection on how images shape perceptions of power and identity, even today. Curator: My pleasure. I think examining colonial-era art requires an awareness of both its aesthetic qualities and its underlying social and political implications.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.