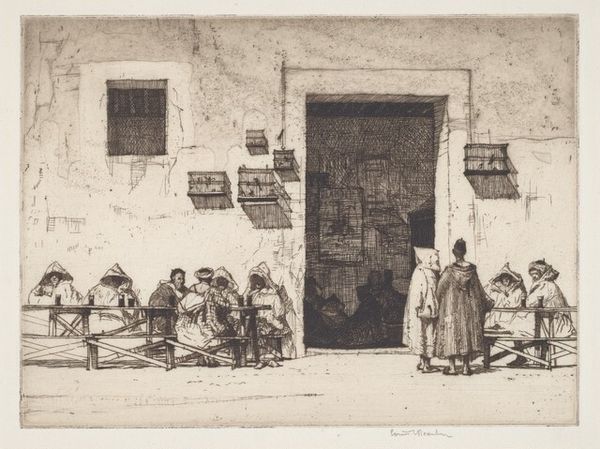

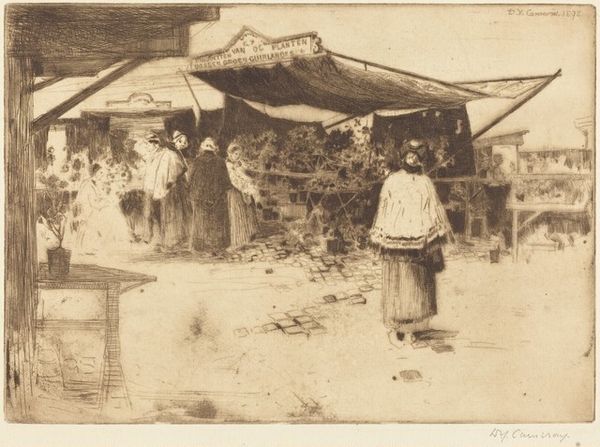

print, etching

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

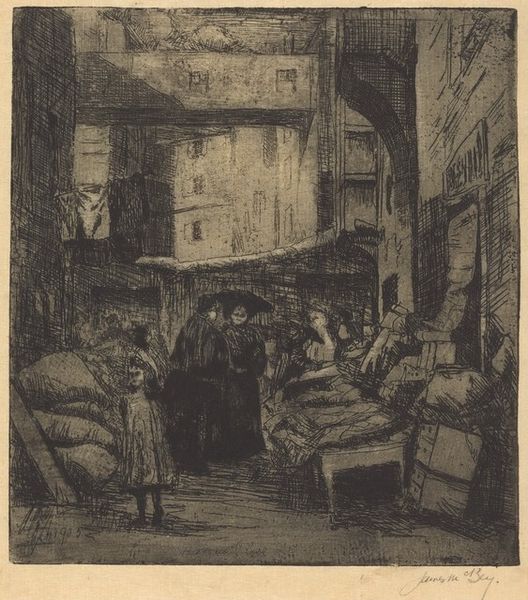

Curator: This print, "The Fountain at Peille, Cote d'Azur", attributed to Earl Stetson Crawford, presents us with a glimpse into daily life, likely from the late 19th or early 20th century. The etching technique offers a compelling window onto the scene. Editor: The mood strikes me as both serene and subtly burdened. There's a communal aspect, but the women around the fountain also seem preoccupied, perhaps weary from the routines depicted. It feels like an observation of women in a place that does not give space for them to relax. Curator: Indeed. Fountains in cityscapes often symbolized more than just access to water. They can represent community gathering points, a shared space of both necessity and social interaction. Water itself, in iconographic terms, often carries cleansing or renewing properties, both literally and figuratively. Editor: I'm interested in that shared space. Note the sharp contrast between light and shadow – a powerful compositional tool, of course, but also symbolic, isn't it? The women are caught between these extremes, illuminating their labor while perhaps underscoring the socio-economic divisions of the time. Curator: Absolutely, consider the implied narratives woven into this cityscape. The clothing, the tasks, and even the architecture point towards the continuities of traditional lifestyles. The very act of etching itself – a labor-intensive process – mirrors the diligence of these women's lives. Editor: And how that diligence so often goes unacknowledged! While the landscape evokes a picturesque charm, one must remember that those scenes exist as lived realities for so many women doing the everyday labor. Curator: Yes. We bring our own perspectives to bear when viewing historical artwork. As much as Crawford documents a moment, we analyze through the lenses of our contemporary concerns with gender, class and the nature of work itself. Editor: Exactly. Seeing the figures clustered around the fountain, I'm reminded how essential these gathering spaces were—and in some places still are—for women’s networks and support systems in many patriarchal societies. Curator: Ultimately, it prompts a dialogue. We can appreciate Crawford's artistic skill, the careful rendering of light and texture, whilst simultaneously acknowledging the unsaid histories that the artwork prompts us to examine. Editor: Right, the past speaks to us, sometimes more loudly than others, if we take a moment to really see, really question what is there and is not represented in visual cultures and what its implications were.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.