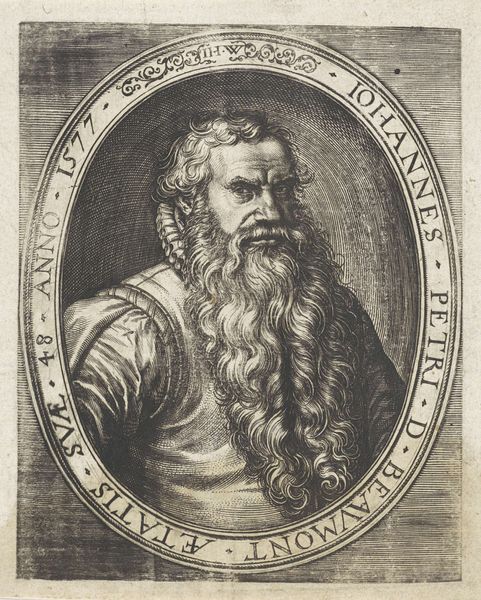

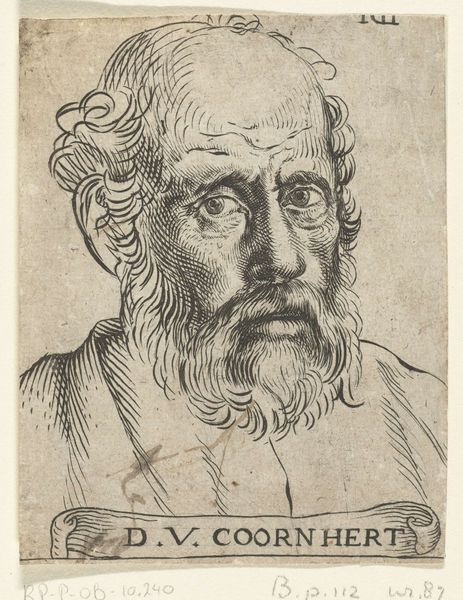

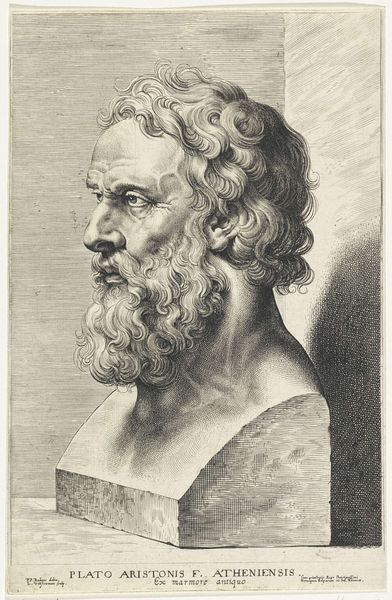

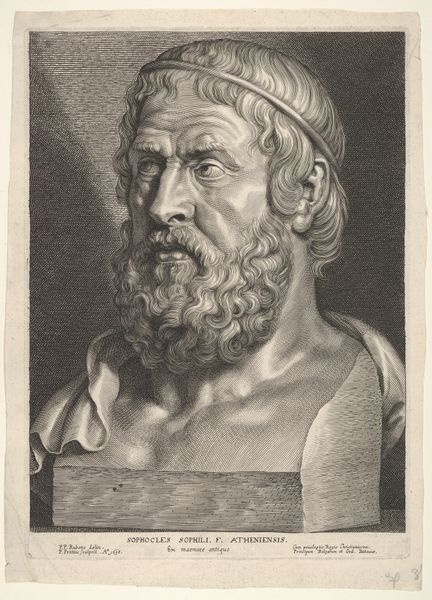

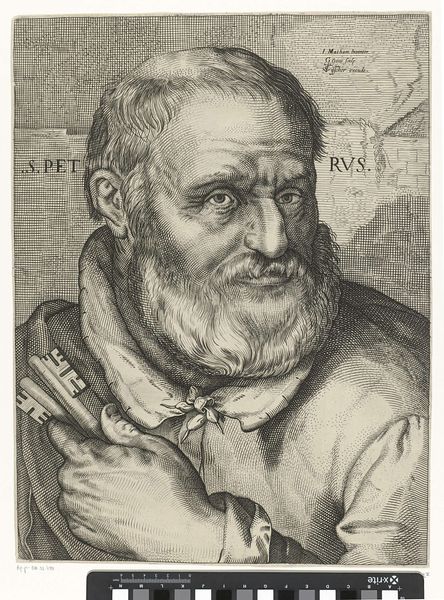

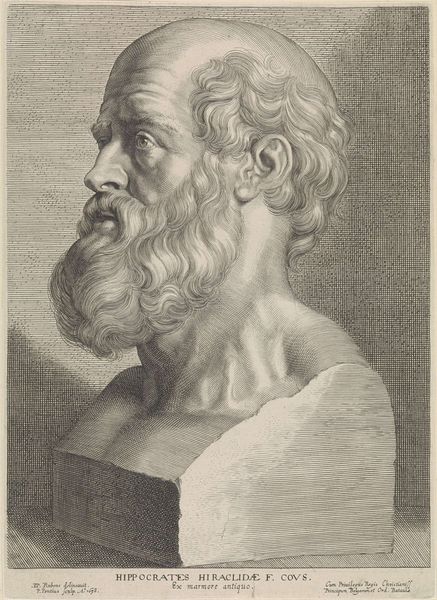

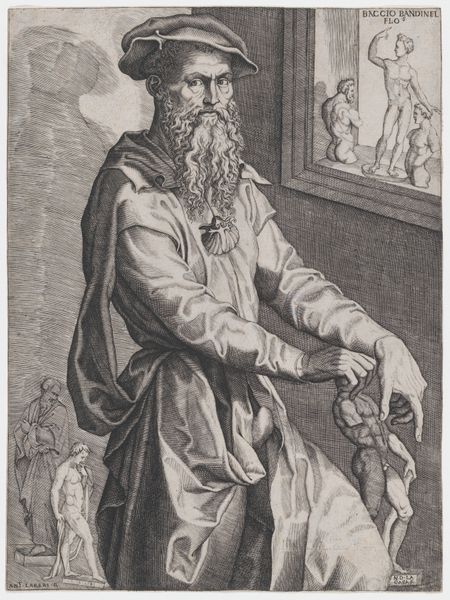

engraving

#

portrait

#

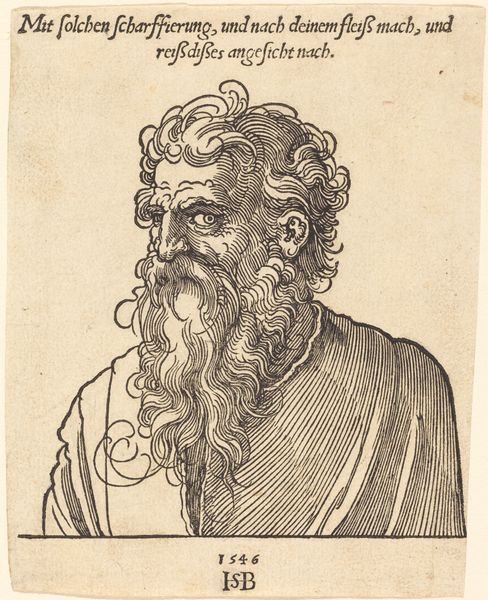

facial expression drawing

#

baroque

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

portrait reference

#

pencil drawing

#

line

#

animal drawing portrait

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

facial portrait

#

engraving

#

portrait art

#

sword

#

fine art portrait

#

digital portrait

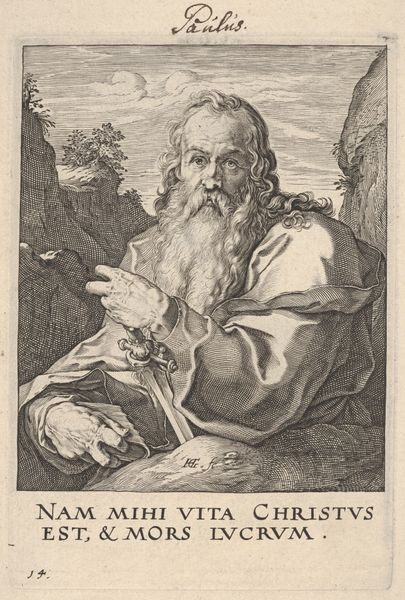

Dimensions: width 357 mm, height 469 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

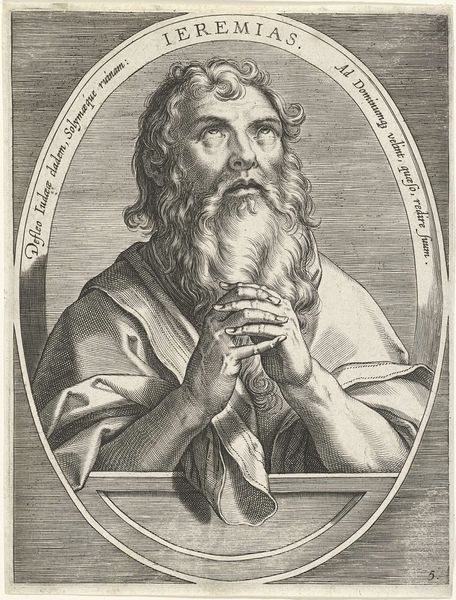

Curator: This engraving presents “Apostel Paulus,” made sometime between 1604 and 1638 by Gerrit Gauw. It captures a portrait of Paul the Apostle. Editor: There's an arresting somberness here. The texture is striking, too – incredibly detailed lines bringing forth depth and a tactile sense to the face, hair and beard. You can almost feel the weight of that sword. Curator: Absolutely. The use of engraving allows for a precise control over the lines. But let's consider the image in relation to religious shifts of the period. How do portraits such as this shape individual perception of authority? Editor: What grabs me is the sword; it’s not just an object; it signifies power, sure, but also a craftsman’s ability to render metal's sheen and weight on a flat surface using tools. What about the socio-economic status of such artists in the 17th century? How does such an image reflect craftsmanship's role in constructing narratives around sainthood? Curator: Good point. In the Baroque era, engravings were an accessible way to circulate images and ideologies. The texture isn't just aesthetic, is also directly linked to how widely the artist wanted his idea shared within different socio-economic groups. Editor: Exactly. And what of the distribution of these engravings? They are a testament to a shift in devotional practices where ownership and visibility could be mass produced. That’s not only the making of an image but also a radical shift in materiality of the devotion, from unique altar pieces to a series of multiples made possible by new workshops specializing in print media. Curator: Indeed. Engravings like “Apostel Paulus” provide insight into the power dynamics within religious representation. Who had access to the image, how were the skills developed, what purpose do portraits like this ultimately serve? Editor: We see that process of devotion in multiple in different locations and it makes one consider both the artist and the viewers more intimately. I am captivated to see that an image can travel this far in time and continues to invite critical inspection today. Curator: And it pushes us to reflect on image circulation in contemporary society too! What lasts, what fades away, and how meanings are created through different materials, approaches and access to them across time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.