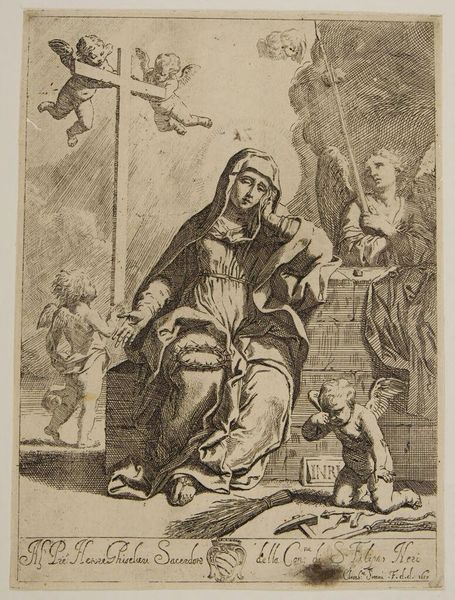

print, etching

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

figuration

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 280 mm (height) x 205 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Editor: So, here we have Elisabetta Sirani's "Mater Dolorosa" from 1657, an etching currently held at the Statens Museum for Kunst. It’s a pretty small, delicate piece, but the scene it depicts feels very heavy with emotion. What catches your eye when you look at this image? Curator: What strikes me is how this print reflects the power dynamics of its time. Consider that Elisabetta Sirani, a woman artist in the Baroque period, is creating religious imagery – traditionally a male-dominated arena. How might her perspective as a woman shape the way we interpret the Virgin Mary’s sorrow here? Editor: That's interesting! I hadn't really considered Sirani's own position. Curator: Exactly! Look at how Sirani presents the instruments of the Passion: the nails, the hammer, the crown of thorns. They are not merely symbols but powerful indictments of worldly violence. The weeping angels too – are they just stock figures or something more? What's the overall effect on the viewer of staging suffering so intimately, then widely distributing that representation as a print? Editor: It feels very personal, but I guess the point of prints like this was for them to be distributed, to almost standardize that feeling of grief and make it widespread. Almost propaganda, in a way? Curator: Yes! You've hit upon a key tension in art history - how do we reconcile sincere artistic expression with the socio-political function of images, particularly within institutions like the Church? Religious imagery like this served to reinforce societal values and solidify institutional power. The artist works with the means that are accessible at this point of history. Editor: So, Sirani's "Mater Dolorosa" isn’t just a devotional image, it’s a statement on societal power, faith, and perhaps even female authorship. That's a lot to unpack from a seemingly simple etching! Curator: Precisely. It highlights the importance of considering not only what we see but also who made it, and within what cultural landscape it was produced and then consumed by viewers throughout history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.