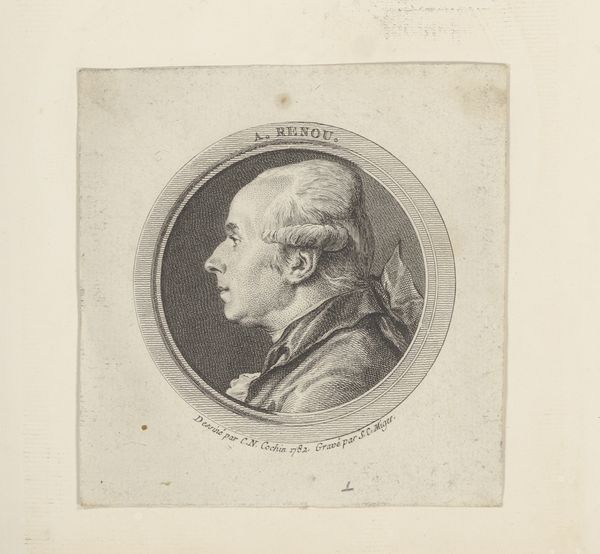

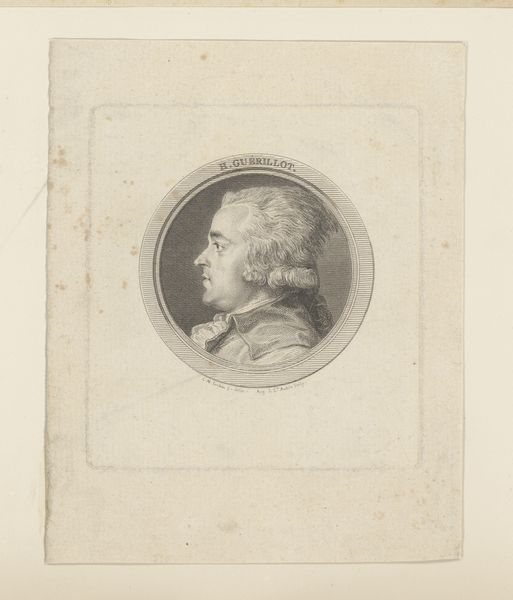

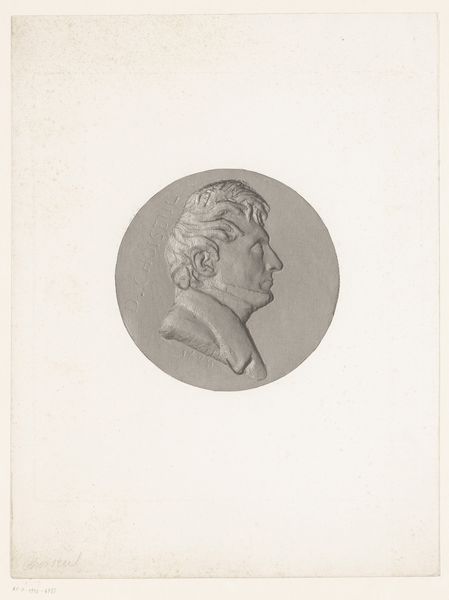

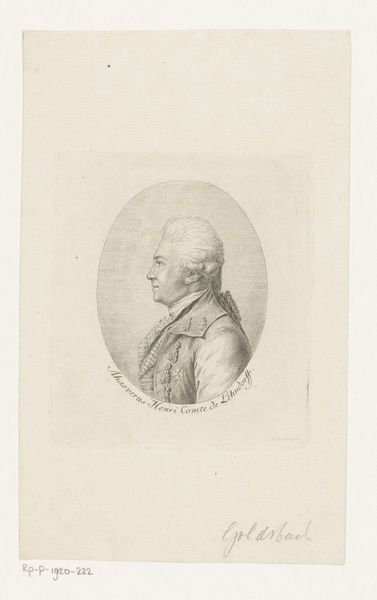

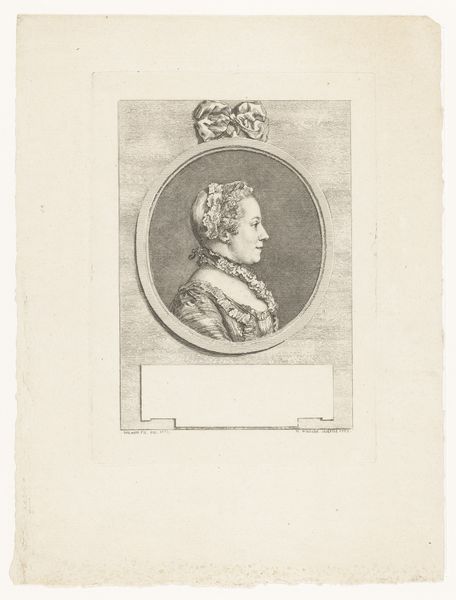

engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 100 mm, width 94 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Louis Jacques Cathelin’s “Portret van J. Gosseaume” from 1781, an engraving. I am struck by the detail achieved through this medium. How can you read this artwork from a materialist perspective? Curator: Considering its context, engraving served specific social purposes. Reproducing images, especially portraits like this, expanded access, circulating likenesses beyond the elite who could afford painted portraits. Notice the inscription. Editor: Yes, “C.N. Cochin del. 1781 L.J. Cathelin." Is that referencing the process? Curator: Exactly. Cochin was the designer; Cathelin, the engraver. Think about that division of labor. It reflects the specialization inherent in printmaking workshops, almost an assembly line approach to art production. What about the paper itself? Does it seem standardized? Editor: It does. It’s not some bespoke vellum. Curator: The availability and relative cheapness of paper played a crucial role in the dissemination of these images. Consumption drove demand, impacting the entire artistic process from design to distribution. The line work here communicates a great deal of textural information about status through attire. What does it communicate? Editor: That the sitter wants to appear refined, fashionable, yet also stern and official through the stark, controlled lines? Curator: Precisely. This wasn't merely art for art's sake, it was a manufactured product woven into the fabric of 18th-century society. Editor: I never considered engravings as being 'manufactured' goods, rather than artworks! Curator: By understanding its production, distribution, and consumption, we uncover this portrait’s true significance beyond just a likeness of a person.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.