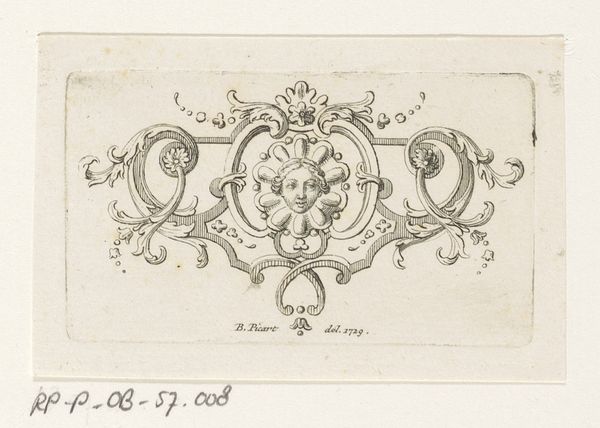

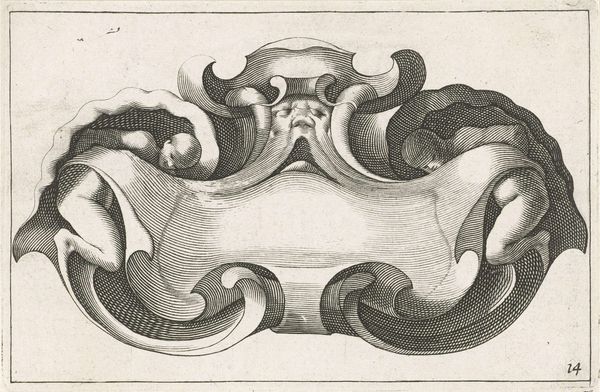

drawing, print, ink, engraving

#

portrait

#

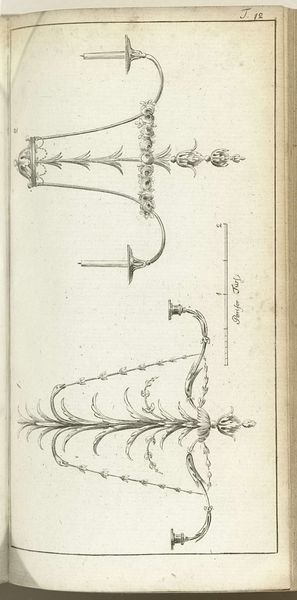

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

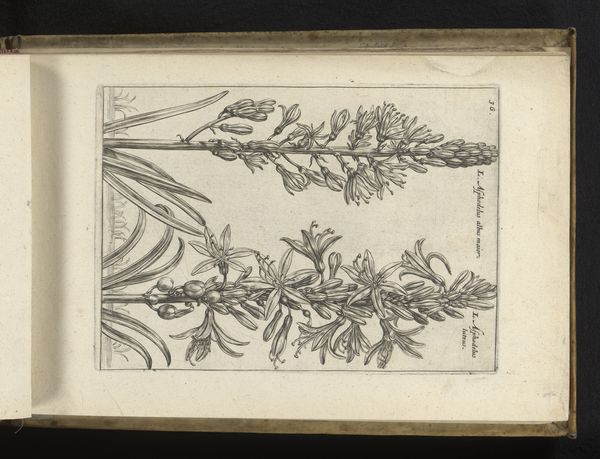

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

line

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 148 mm, width 203 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

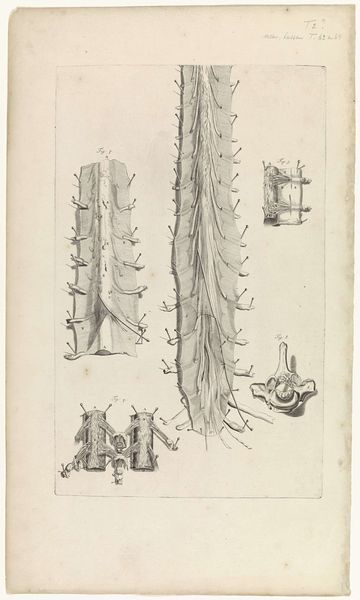

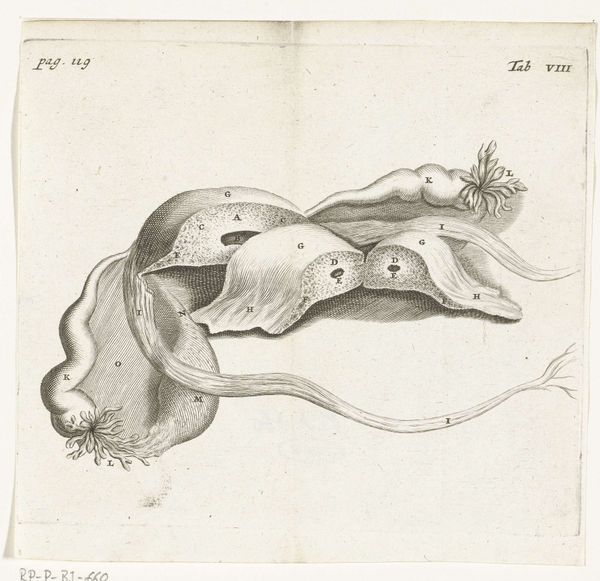

Curator: Looking at Hendrik Bary’s “Anatomical Illustration of the Female Genitalia” from 1672, currently held at the Rijksmuseum, one is immediately struck by the labor involved in its creation. As a print and drawing rendered in ink, likely through engraving, it offers a detailed view of the female anatomy. The social context, during a time when anatomical knowledge was both expanding and tightly controlled, adds layers of meaning. Editor: Well, hello! It has the aura of forbidden knowledge carefully unwrapped—you know, with secrets sketched out with delicate precision. The whole thing kind of pulses with, not exactly life, but an intense, probing curiosity. And doesn't the almost symmetrical composition give it an unexpected… elegance? Curator: The choice of engraving as a medium is significant. The act of producing this detailed drawing involved a specific set of skills, tools, and labor. This print allows for dissemination and study of the work, influencing anatomical understanding across a broad spectrum of educated society at the time. Editor: Absolutely. Thinking about materials and consumption brings up the act of reproducing it for study; it’s so tactile, but also kind of unsettling. Do you feel the almost clinical detachment heightened by Bary’s linear precision? It’s baroque rigidity and clinical analysis colliding! Curator: Indeed. Bary’s use of line work, characteristic of academic art, highlights specific elements while creating depth. The materials themselves—the paper, the ink—were commodities, part of a larger system of trade and intellectual exchange in the 17th century. Even the artist’s skill became a commodity in service of scientific endeavor. Editor: So well articulated! When I look closer, though, past all the diagrams and dissections, there's a hint of something quite profound; what an evocative, yet dispassionate study this engraving continues to reveal about then-modern understanding of both science and our corporeal selves. Curator: Precisely. Thinking about how reproductive technologies influence understandings today vis-a-vis its place then in intellectual exploration, really emphasizes just how mutable perception really is when viewing and re-viewing artwork. Editor: Agreed. Such an odd blend of vulnerability and cool examination, even now. Thanks for exploring with me!

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

In 1672, physician and anatomist Reinier de Graaf published his De mulierum organis about the female reproductive organs, with prints by Hendrik Bary. De Graaf was the first to conclude that a foetus was the product not just of a man’s seed, but also of a woman’s egg. He discovered what he called blisters, which later became known as Graafian follicles.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.