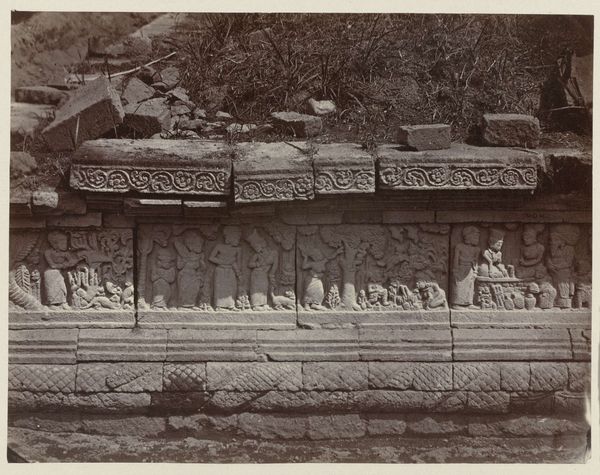

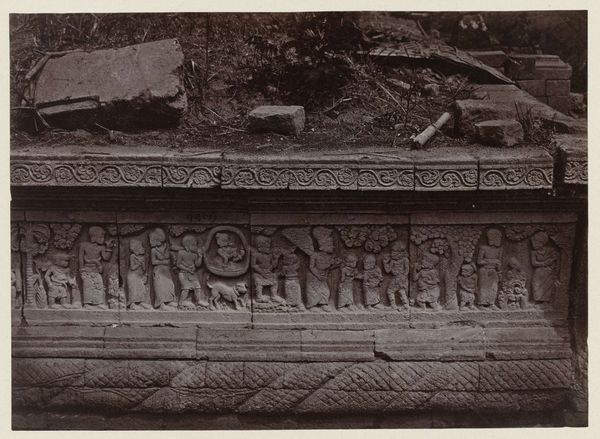

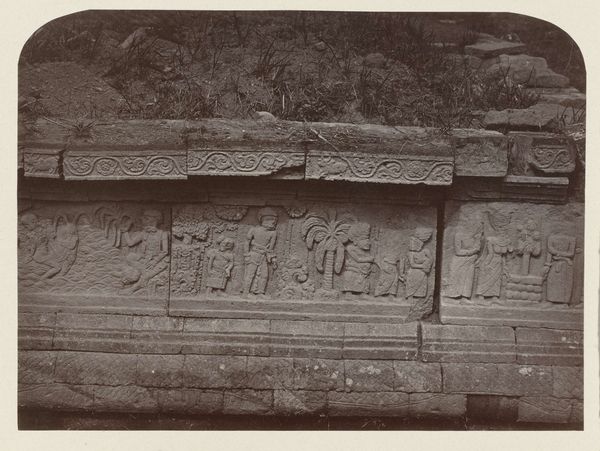

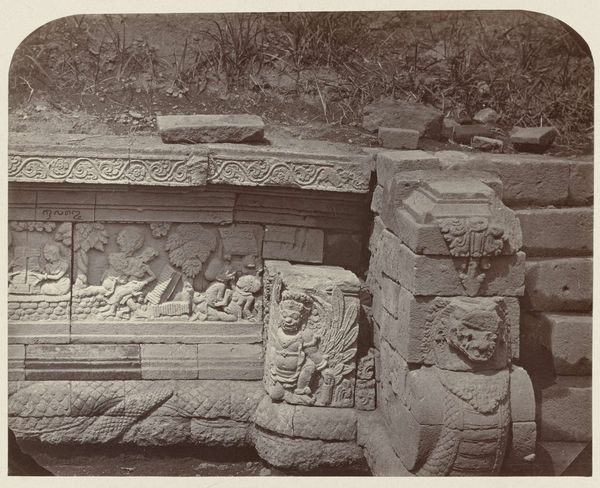

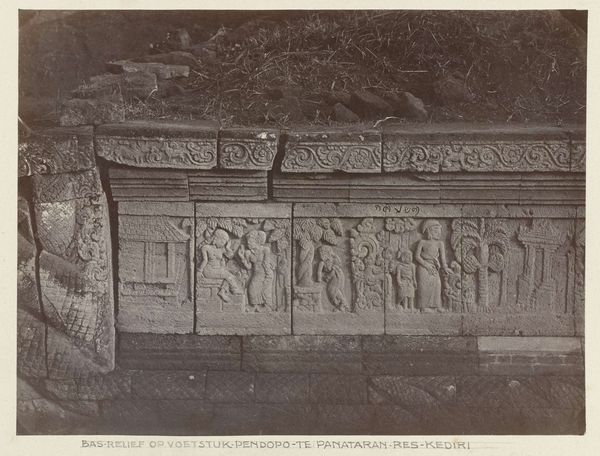

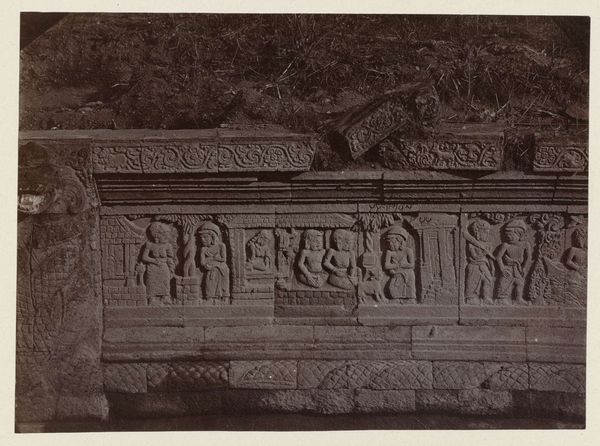

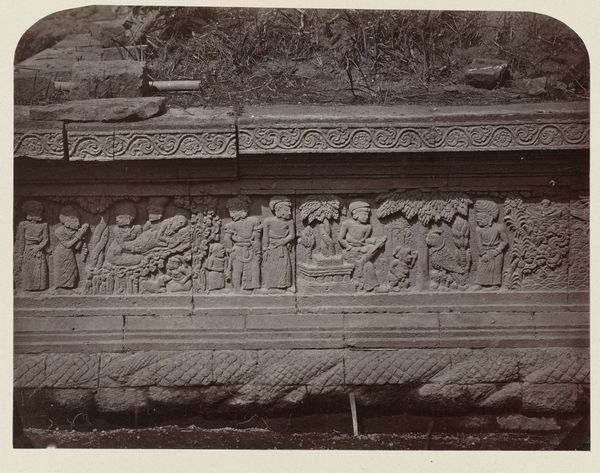

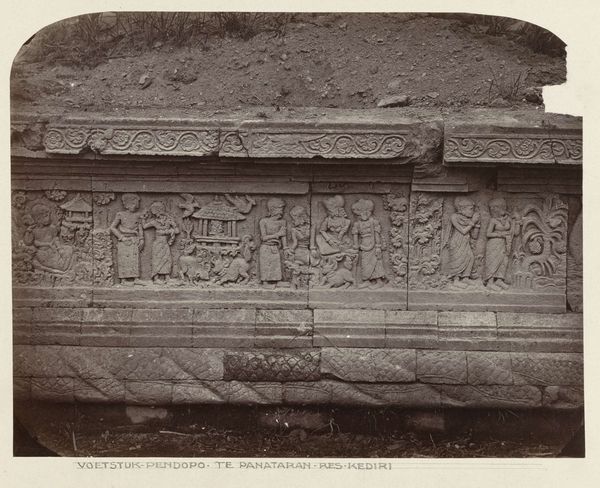

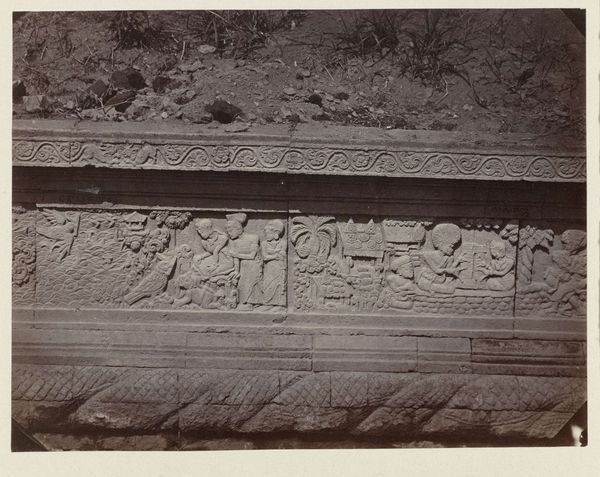

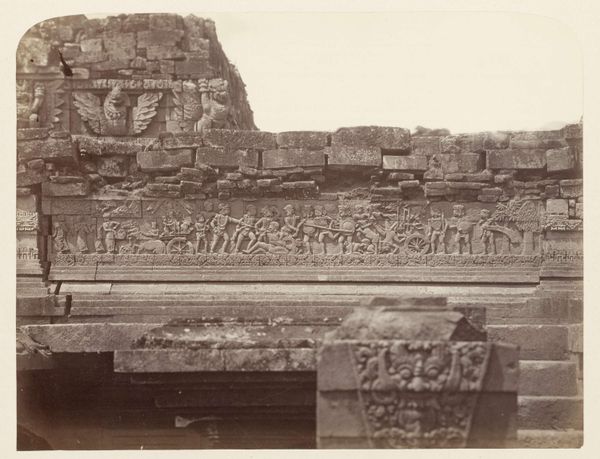

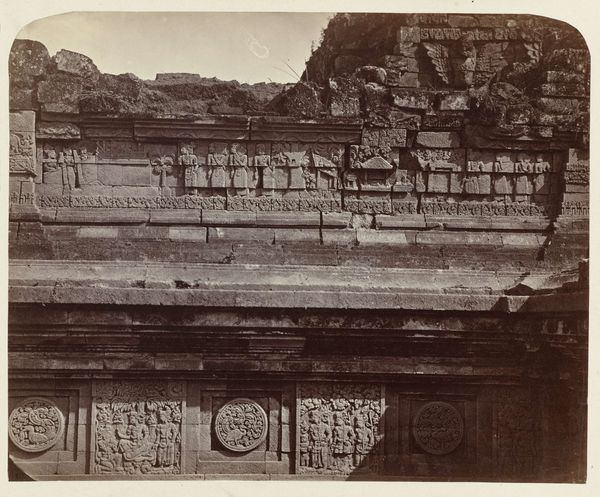

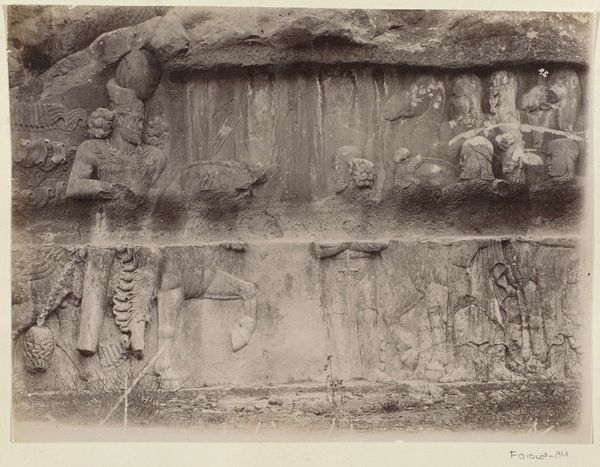

Basreliëf op het pendopo voetstuk aan de westzijde van candi Panataran. Possibly 1867

0:00

0:00

carving, print, relief, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

carving

# print

#

asian-art

#

relief

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 210 mm, width 260 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a gelatin silver print dating back to around 1867. The photographer, Isidore Kinsbergen, captured a bas-relief on the pendopo base at the west side of Candi Panataran. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the scale of this. You get such a clear sense of the texture, the material of the stone. There's a real weight to it. Curator: Indeed, and Kinsbergen's photographs of the Panataran temple complex served as invaluable documents, capturing the temple's state during a period of colonial interest and archaeological exploration. Editor: Considering it's a photograph of a carving, I'm also thinking about the labor involved, both in creating the relief itself and in Kinsbergen’s photographic work. The extraction of silver, the preparation of the gelatin, the printing… these all speak to complex systems of labor and value. Curator: Precisely. It reflects how visual culture played a crucial role in shaping Western perceptions of Southeast Asian art and history. Kinsbergen’s photographs, including this one, were exhibited internationally and disseminated through publications. Editor: It makes you wonder about the hands that shaped this narrative, doesn't it? I mean, we are seeing this through a distinctly colonial lens. Look how the bas-relief scenes depict what seems like domestic activities and royal processions… Do we know whose story it is telling? Curator: These carvings are believed to illustrate episodes from Javanese folklore and religious stories, offering insights into the cultural beliefs and social structures of the time. The photographic documentation aimed to classify and understand this cultural landscape, thus creating and disseminating specific, politically shaped ideas. Editor: Right, like packaging and branding a distant, exotic culture. Even this method of documentation, with the gelatin silver print, turns the stone relief into a commodity of sorts. I suppose, now, what I'm struck by most is the power dynamic imbued in both processes of image creation. Curator: Yes, understanding the colonial context in which this image was produced is essential for interpreting not just the photograph itself but also the role of institutions in shaping the public understanding of art and cultural heritage. Editor: Looking at it through that frame, you can almost feel the weight of history in the image—not just of the temple itself, but of the colonial gaze that preserved and presented it to the world. Curator: Absolutely, it reminds us of the politics inherent in how we come to know the art of the past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.