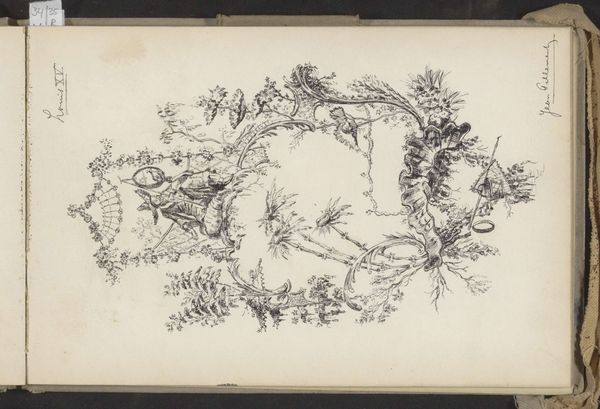

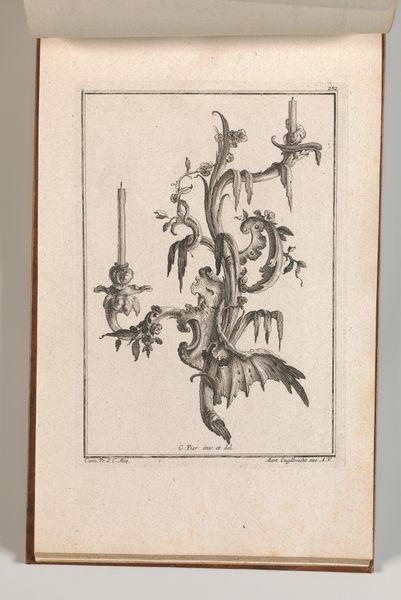

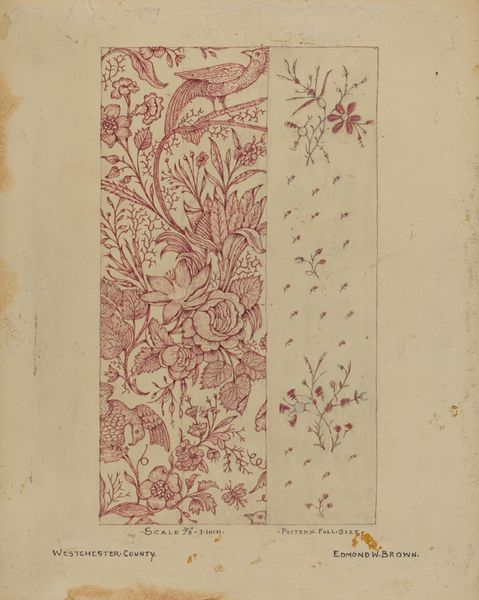

A New Book of Chinese Ornaments. Invented & Engraved by J. Pillement 1755

0:00

0:00

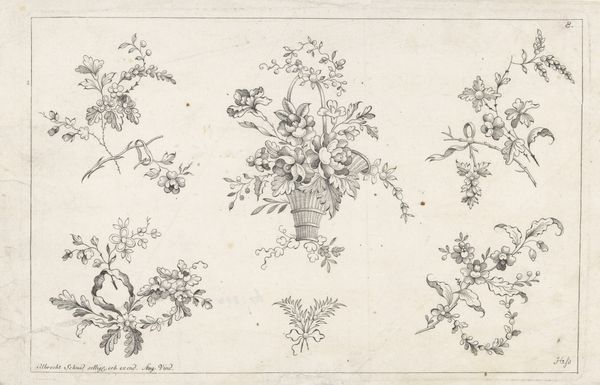

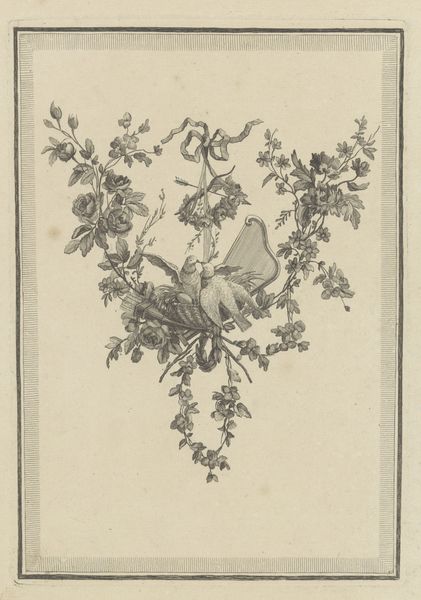

drawing, ornament, print

#

drawing

#

ornament

# print

#

asian-art

#

line

#

decorative-art

#

rococo

Dimensions: Sheet: 18 in. × 11 5/8 in. (45.8 × 29.5 cm) Plate: 16 3/4 × 10 5/8 in. (42.5 × 27 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: What strikes me first about Jean Pillement’s print, "A New Book of Chinese Ornaments," from 1755, is its dreamlike quality, its almost weightless ornamentation. Editor: I agree. There’s an airy whimsy that really belies the complex historical context this sort of "chinoiserie" represents. Curator: Tell me more. Editor: Well, the imagery isn't really Chinese, of course. It's a European fantasy, a pastiche of imagined Eastern motifs filtered through a Rococo sensibility. Consider what that fantasy obscures—the realities of colonial trade, the Opium Wars looming on the horizon... It speaks to power dynamics. Curator: Yet the visual language is captivating, no? Monkeys and pagodas, delicate foliage all rendered in such intricate detail. These ornaments, these repeated images, offered a vocabulary. Architects, furniture makers, and other artists used it as a kind of visual shorthand to evoke the exotic Orient. They were building blocks for dreams, whether realized or not. Editor: And those dreams were inextricably linked to global power structures, right? The desire for luxury goods, the appropriation of culture... this wasn't just innocent aesthetic appreciation. Curator: I concede your points. It's not devoid of the implications and impositions of power, but also, can we think about the psychological allure of imagined otherness? Symbols resonate, after all, on multiple layers. Pillement wasn’t simply making copies; he was crafting archetypes, feeding a deeper longing for escapism. It points to something profound in the collective unconscious. Editor: I’m skeptical about collective unconscious, but I agree that these images carry enormous psychological weight. Today we read them, not just as pretty designs, but as emblems of a complex history, fraught with power imbalances and cultural appropriation. We need to remember to talk about those contexts. Curator: It’s hard to deny the problematic nature of it. Perhaps it’s possible to look beyond, or maybe it's a visual vocabulary we're no longer supposed to speak? Editor: A complex knot, indeed, tying desire, aesthetics, and political consciousness. Curator: It truly complicates the narrative and shows a wider breadth than simply a picture on a wall.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.