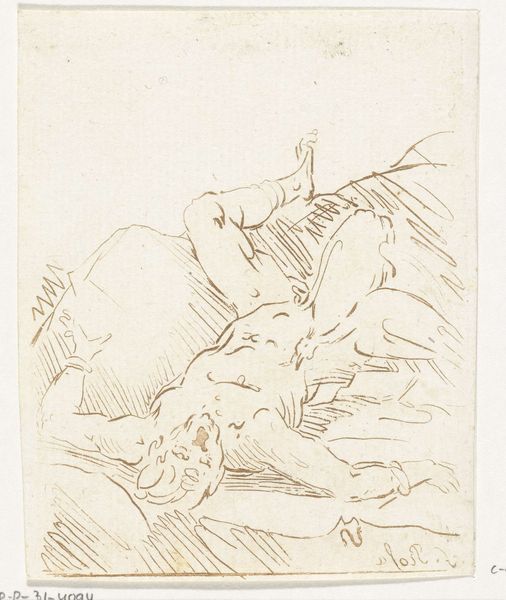

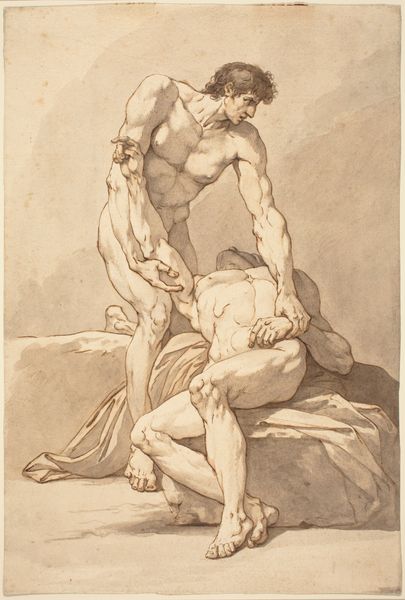

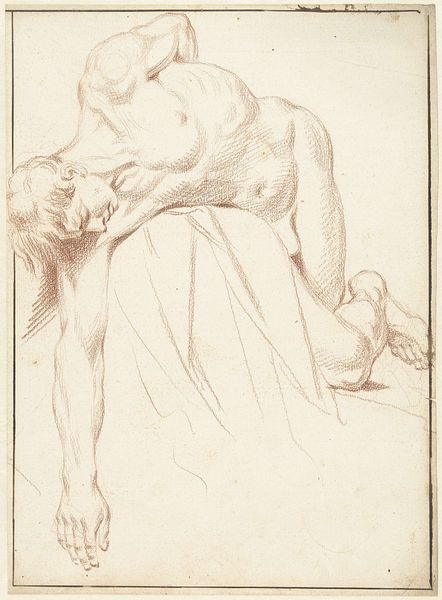

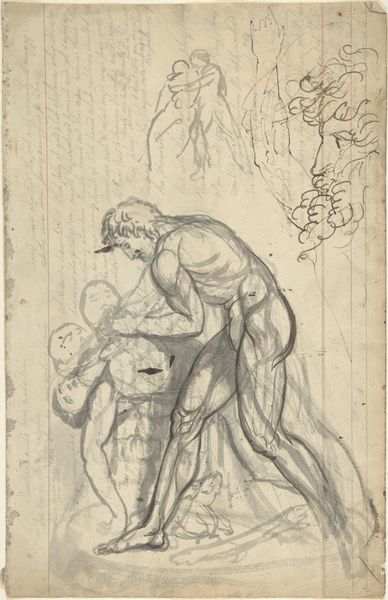

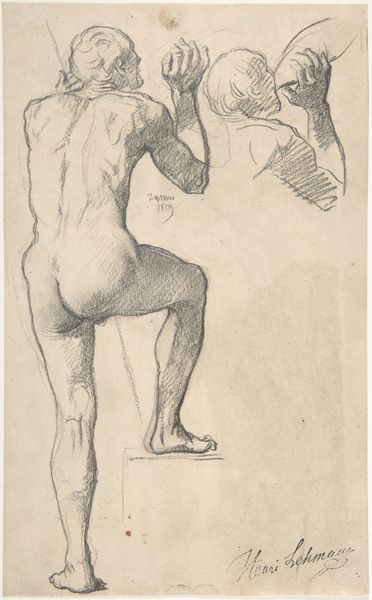

Menelaus and Patroclus, after the Antique (recto and verso) 1770 - 1778

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, ink

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

figuration

#

ink

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

nude

Dimensions: Sheet: 9 7/16 in. × 7 in. (24 × 17.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

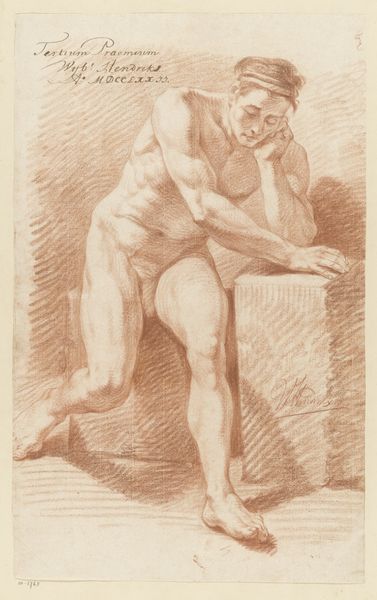

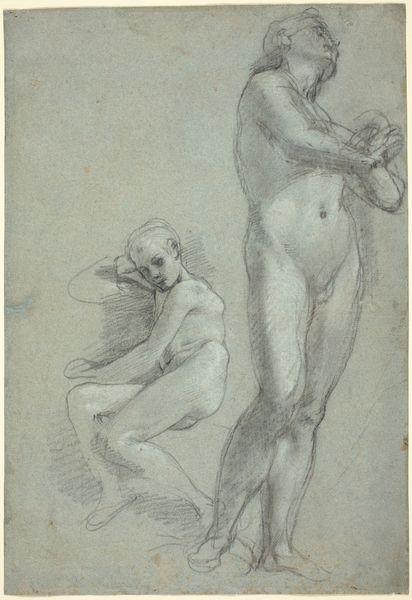

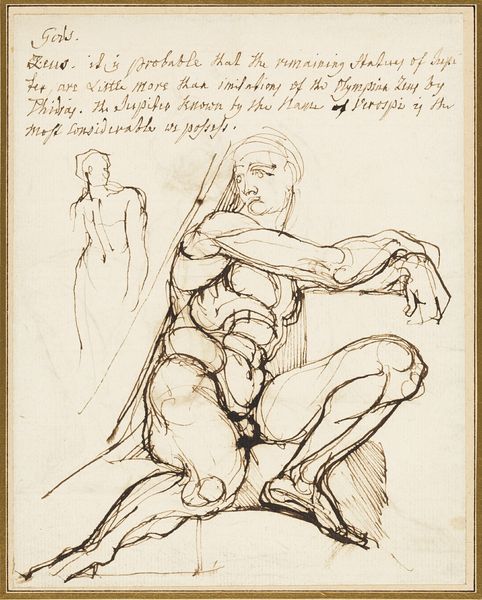

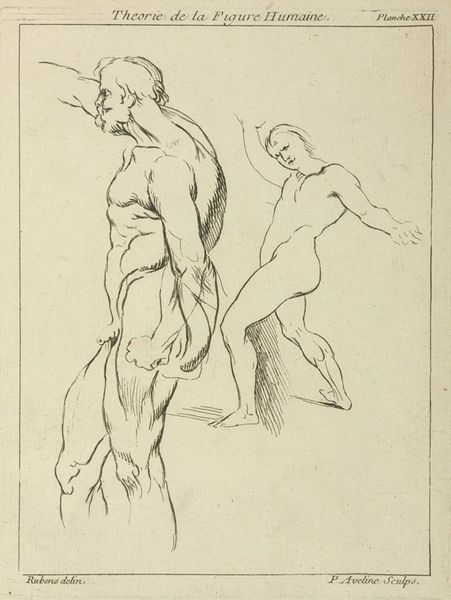

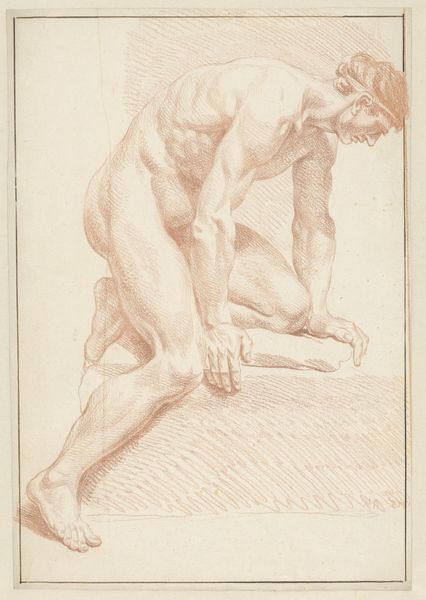

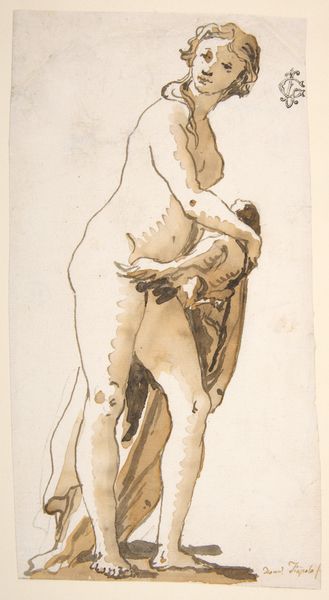

Curator: This ink drawing presents a rather brutal depiction of Menelaus carrying the body of Patroclus. It's titled "Menelaus and Patroclus, after the Antique (recto and verso)", created by Henry Fuseli sometime between 1770 and 1778, during the Neoclassical period. Editor: Stark. Almost aggressively masculine, wouldn’t you say? The way the ink cross-hatching models the musculature… it feels more like a display of power than an expression of grief. And such a rudimentary use of ink; looks like iron gall, judging by its colour. Curator: It is forceful, isn’t it? Fuseli's drawings often lean towards the dramatic, bordering on the macabre. Menelaus's stance is strong, legs firmly planted. This rendering, being "after the antique," recalls the earlier Roman marble sculpture—now viewed in the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence. It represents something very important. In its own time, the sculpture could be seen as evidence of Roman Imperial continuity, especially in contrast with fragmented empires and divided governments. Fuseli, living through different historical contexts, could very well have been grappling with the fragmentation he knew while simultaneously evoking Roman antiquity and an empire with supposedly eternal values. Editor: Interesting. I was going to say that all those sketchy lines almost appear hurried, an exercise maybe? Not that academic line, repeated almost like an obsession. Look, you can even tell the direction that the tool was pulled just based on the pooling of ink; each mark made deliberately, emphasizing process in its very conception. Did Fuseli ever work with found objects at all? How aware was he of how ink degrades over time? Curator: There are no historical records mentioning Fuseli's utilization of found materials, but his intense awareness of classical art, myth, and history definitely informs his work. Look closely, and the idealized physique morphs into something more human, more burdened, when depicted by his own hand. Notice how his crosshatching brings a tension, not just to the anatomy but to the mood; not classical, even hinting at the Romantic to come, later in life. This shift isn't about degradation of material, but rather Fuseli's active re-envisioning of historical concepts and representation of power. Editor: Re-envisioning yes, but you can never totally get rid of material history: everything decomposes. Ink darkens, paper yellows… And you can never erase your mark! Look, Fuseli did exactly that by sketching. Both he and we, the viewers, become involved in production. He may have thought he had the vision; what is revealed over time, however, demonstrates how everyone is involved. Curator: Perhaps that ongoing dialogue—between artist, material, and viewer, mediated by history itself—is part of what keeps art relevant, no? It is not static; and certainly carries with it something universal. Editor: Yes, it reveals its labour.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.