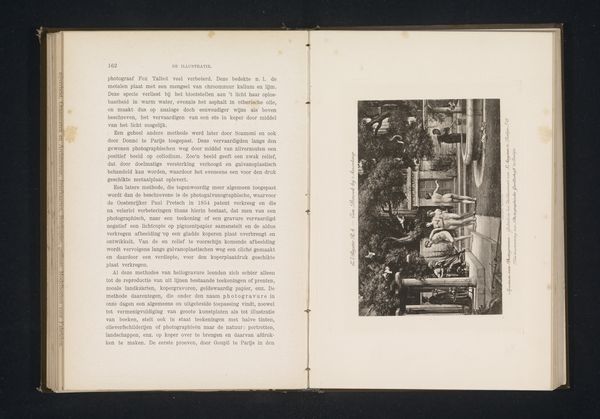

print, photography

#

portrait

#

still-life-photography

# print

#

photography

#

realism

Dimensions: height 64 mm, width 90 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's dive into "Mr. French," a photographic print dating back to before 1895. Alice Lee Snelling-Moqué is credited with this image. It's interesting, what's your initial reaction to it? Editor: It feels incredibly staged, almost theatrical. There's something unsettling about the gaze of this animal, but also the complete absence of any real habitat or surrounding context beyond what reads to me like some stage design. Curator: Absolutely. We're looking at what seems to be a still-life portrait, rooted in realism, although I agree that the staging undercuts any attempt at naturalism. Given Snelling-Moqué’s likely connections, one begins to ask about performing identity here: she may have been seeking to highlight the "Americaness" or perhaps some kind of perceived domestication of what are deemed wild or unruly characters. Editor: Right, I wonder about the historical context of photographing animals in zoos during this period. Zoos were, and still are, colonial projects to control, collect, and classify. What does it mean to put Mr. French on display this way, framed as this docile figure when these settings are incredibly violent spaces that produce these affects? Curator: And "Mr. French" specifically? There's a humanization inherent in the title and staging. Does it serve to elicit sympathy, or does it other him further by attempting to bring him into the realm of the familiar while holding him captive? Perhaps to highlight the zoo's project in capturing exoticism, or also rendering the individual as a consumable spectacle... Editor: Consumable and docile, certainly. Consider the power dynamic. Mr. French doesn't have any agency here, he's at the whim of the photographer, the zookeepers, the whole system that confines him, literally freezing him within this historical narrative. Curator: So, "Mr. French" isn't just a photo of a lion. It's a snapshot of a particular moment in history, layered with assumptions about wildness, captivity, and the human need to control the natural world. A desire for order that seems equally imposed as much as captured here by Alice Lee Snelling-Moqué. Editor: Exactly. It reflects not just on the lion but the gaze directed upon it—a gaze deeply entrenched in hierarchies. By calling attention to that construction, we open up avenues for challenging those very foundations of domination.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.