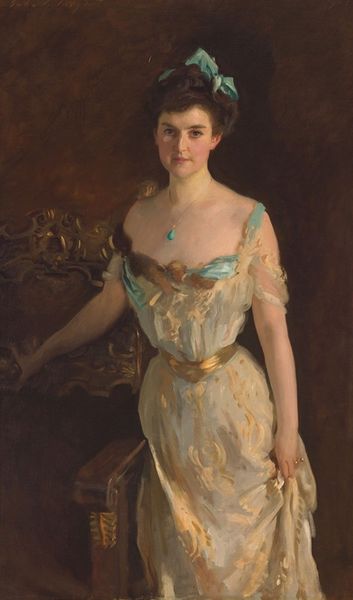

Dimensions: 100 x 80 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Editor: We’re looking at John Singer Sargent’s portrait of *Etta Dunham* from 1895, crafted with oil paints. I'm immediately drawn to the fabric; it’s so frilly and light, it almost seems to float. How does the materiality contribute to the piece? Curator: The lavishness of Etta Dunham's attire is, indeed, striking. Consider the social context: Sargent was a sought-after portraitist for the wealthy elite. The shimmering oil paint rendering silk, lace, and jewelry displays more than artistry— it proclaims status. Are we truly admiring artistic technique or, also, the subject’s capacity to acquire such finery? Editor: I see what you mean. The dress isn't just "painted," it's "produced" to broadcast wealth. So, Sargent’s brushstrokes are part of this process of value creation? Curator: Exactly! Think of the labor behind that dress, from the silk production to its construction. Sargent, in immortalizing Dunham in paint, participates in celebrating this hierarchy of labor, doesn’t he? Does the ‘artistry’ mask exploitation? Editor: So, viewing the piece materialistically prompts us to consider the hands behind every element of the artwork, seen and unseen. Curator: Precisely! Sargent's painting isn't just about aesthetics; it's a visual document of the societal forces at play in 1895. How the materials reflect power. The cost of beauty. Editor: That really changes my perspective on the role of portraiture back then. I will never unsee how the painting and the opulence it celebrates are intertwined. Curator: And remember, that very paint has a material origin with global resource networks as well as industrial applications within the studios – to ask how ‘art’ is constituted, produced and ultimately circulated remains a vital endeavor.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.