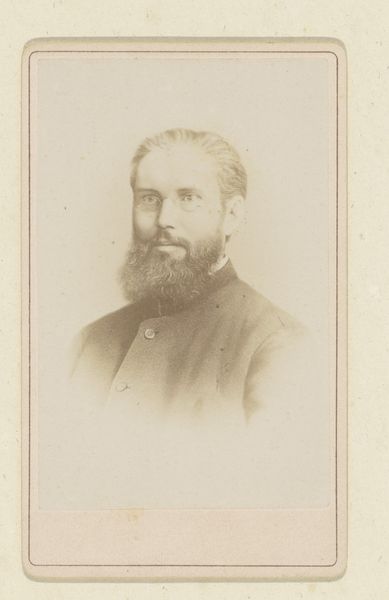

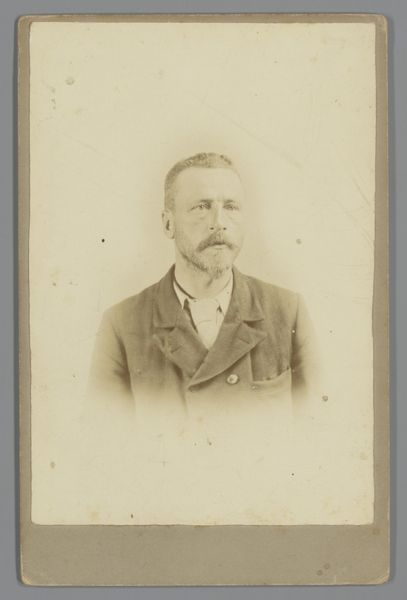

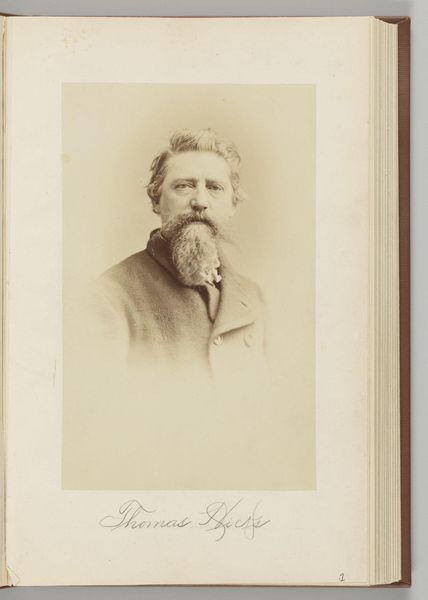

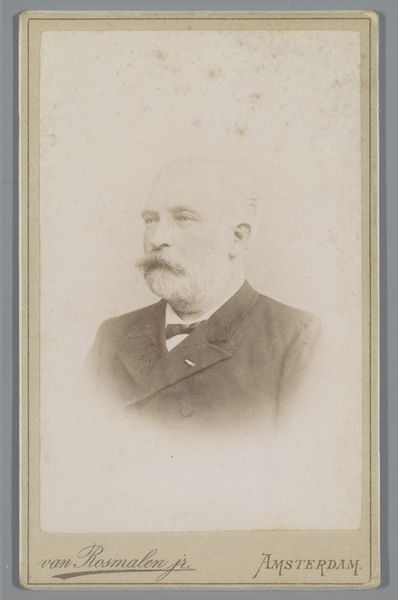

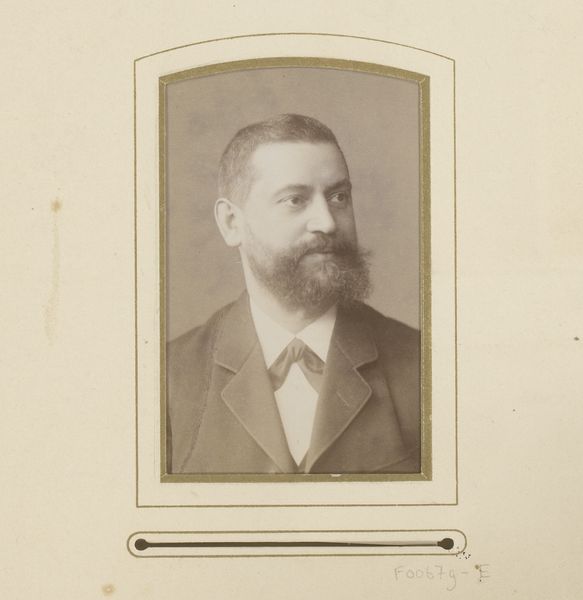

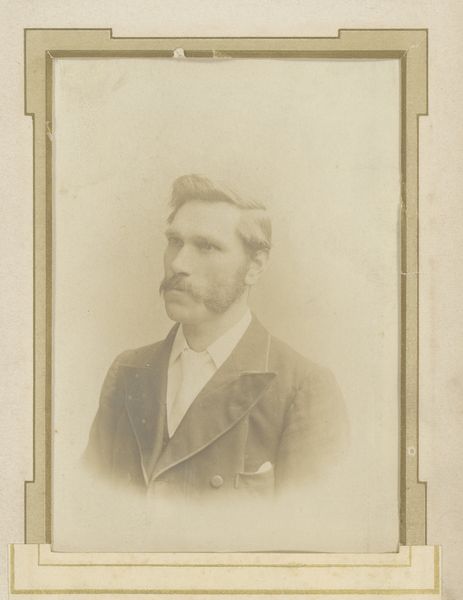

Portret van Chedo Miyutovich, Servisch gezant in Londen en Den Haag 1900

0:00

0:00

adolphezimmermans

Rijksmuseum

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

16_19th-century

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

Dimensions: height 138 mm, width 98 mm, height 165 mm, width 108 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Portrait of Chedo Miyutovich, Serbian Envoy in London and The Hague" by Adolphe Zimmermans, a gelatin silver print from 1900. It's a very formal portrait; the subject looks directly at us. What strikes you about it? Curator: The fascinating thing about this work is its materiality. It’s not just a photograph; it’s a gelatin silver print. That immediately positions it within a specific historical and technological context. What sort of labor and materials went into its making? Consider the photographer, Zimmermans, and his studio in The Hague. He mass-produced images like this for the burgeoning middle class. Editor: So, it’s not necessarily about the artistic vision, but the means of production? Curator: Precisely. Think about the social function this object served. Photography was becoming increasingly accessible. How did this change ideas about representation, memory, and even social status? And look closer at the subject – a Serbian diplomat. Editor: Right! He's part of a specific political network, and his image is being circulated. Curator: Exactly. The photograph becomes a commodity, used for political and personal means. Its existence relied on exploiting material resources to further the commercial needs of studios like Zimmermans', alongside the ambitions of men like Miyutovich. It’s about understanding the web of social relations embedded within its production and consumption. It allows us to consider the photographer's business. Did this photographic process democratize art or commodify image and representation? Editor: So, it's not just a portrait but also evidence of industrial advancement and the burgeoning business of image making. I never thought about it that way. Curator: Indeed. It pushes us to move beyond the individual portrayed and consider the economic and social structures within which this portrait exists.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.