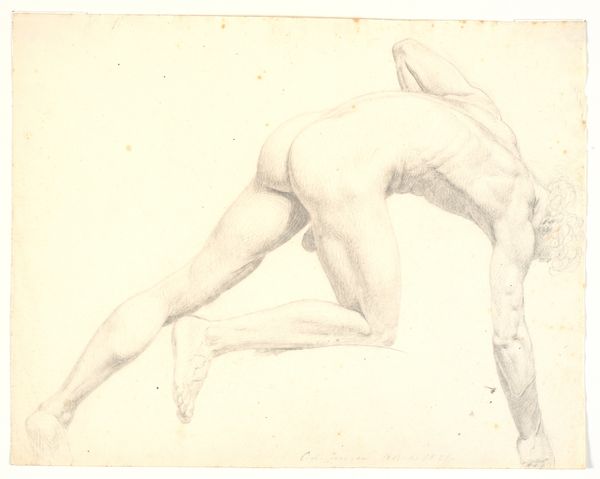

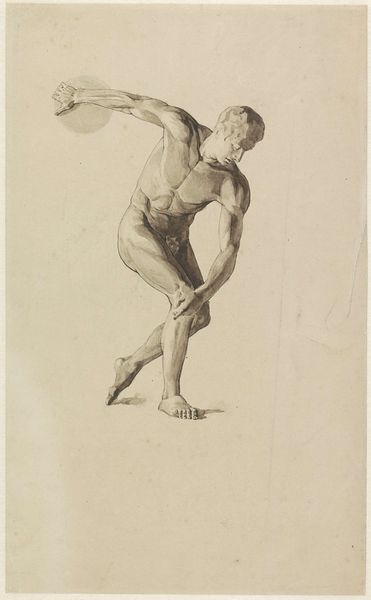

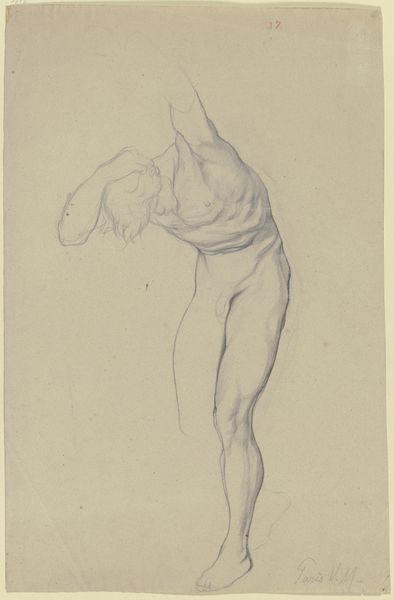

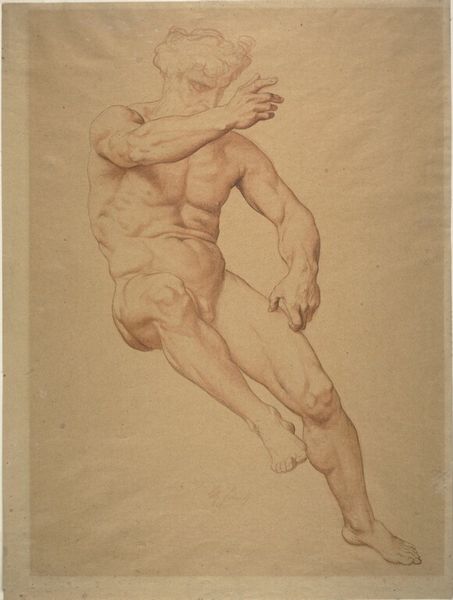

drawing, paper, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

#

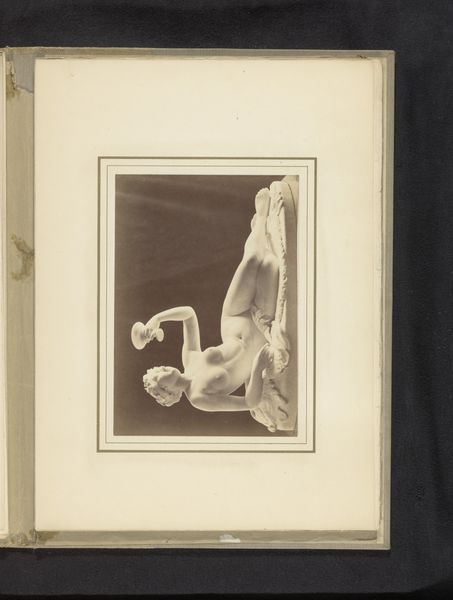

nude

Dimensions: height 215 mm, width 327 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

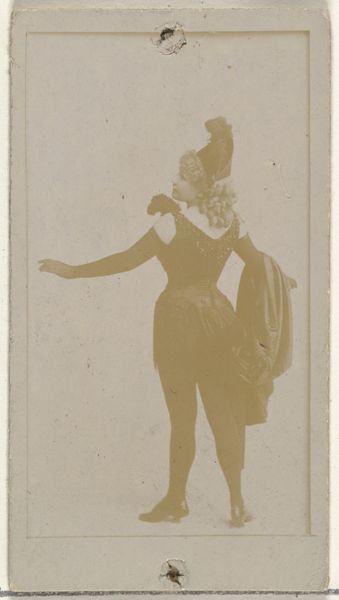

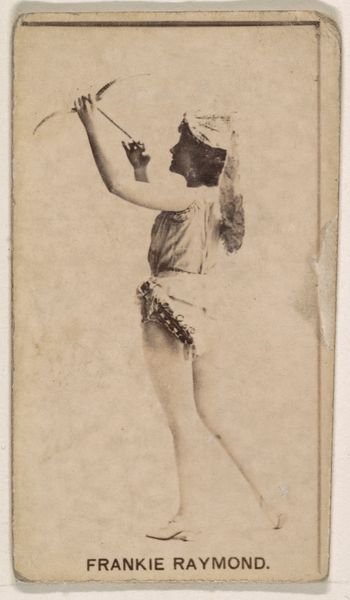

Curator: Stepping in front of Bartholomeus Ziesenis’ work, created around 1812, we encounter "Danseres Annette Köbler, de Pas-de-Zephir uitvoerende," a drawing rendered in ink on paper. There's something immediately captivating about its stark simplicity, isn't there? Editor: Absolutely. The dancer emerges from what seems like an infinite darkness, yet her form is lit so softly. There's a delicate, almost ghostly quality to the entire composition, evoking a sense of solitude amidst performance. It strikes me how contained this dance appears, contrasting sharply with the performative expectation of outward expressiveness. Curator: It is intriguing how Ziesenis presents Köbler not as a spectacle of vibrant movement, but rather as an exercise in form and social expectation, especially given the rise of Romanticism in the era and the cultural perception of ballerinas. There is an uncomfortable tension with how ballerinas are supposed to look like in ballet as women versus how their lived experiences. How they should express joy, ease, and delight in their dances, but in practice have very painful dances, especially in pointe. Editor: That interplay between public expectation and private experience, definitely adds a layer of depth. The historical context, particularly concerning gender and performance during the Romantic era, would suggest we read beyond simple representation. Consider the institutional pressures on women performers – were they given agency or were they merely objectified? Curator: Precisely. Consider, also, the black backdrop—it's almost theatrical, highlighting Köbler’s form and position, but it can also be interpreted as highlighting a blank slate, or void, to reinforce social roles of female expression and repression that they dance through. She has only what has been provided to her through those structures. Editor: And the artist's own role. Ziesenis capturing Köbler might seem to be a straightforward commission. But by choosing this specific pose, and this restrained palette, Ziesenis invites contemplation on those same issues within the theatre institution itself. Are the arts complicit in promoting specific and sometimes limited and problematic expectations of women? Curator: These types of reflections makes this drawing especially poignant in light of today’s conversations around gender dynamics in performance and art’s ability to subvert the status quo, pushing past mere visual documentation into social commentary and political critique. Editor: Indeed. Thinking about this performance in context, its representation, the subtle resistance embedded in what might seem like a straightforward depiction. It underscores the power of historical art not merely to reflect its time but to converse meaningfully with our own.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.