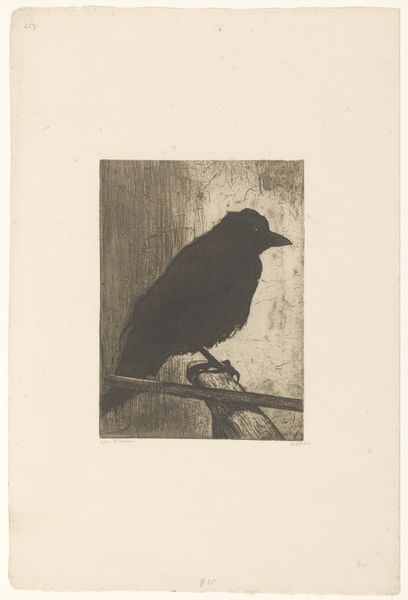

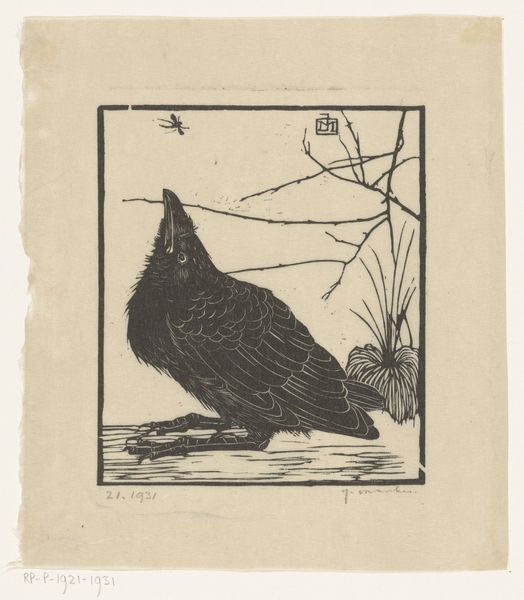

drawing, print, linocut, paper

#

drawing

# print

#

linocut

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

paper

#

linocut print

Dimensions: height 258 mm, width 270 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This striking linocut, titled "Kraai"—that's "Crow" in Dutch—was created around 1910 by Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita. It's currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: It has a really ominous presence, doesn't it? The stark black figure against the paler background—there's a sense of brooding stillness, a visual quiet that feels heavy. Curator: Indeed. De Mesquita was part of a generation grappling with symbolism and finding new ways to depict nature. The crow, of course, is loaded with symbolism in Western culture, often representing death, bad luck, or prophecy. Editor: Given the social upheavals of the early 20th century, one can interpret this imposing image through the lens of socio-political angst. Were viewers, then and now, perhaps primed to perceive more than just a bird in this stark depiction? The blackness almost swallows the detail. Curator: Certainly. And the linocut medium itself – with its bold, graphic quality – lends itself to strong, declarative statements. He was simplifying forms, seeking to capture the essence of the subject. It also worth to say that his approach has clear references to expressionism, but more restrained. The influence of the Art-Nouveau movement is also quite notable in this graphic. Editor: And the setting further complicates this reading: is it meant to evoke decay? The placement of the leaves feel almost deliberately staged within a framed boundary that imprisons its subject. What statement, perhaps political, is being made here about being caged in? Curator: The bordered framing of this depiction can be understood through de Mesquita's complex personal identity. Of Portuguese-Jewish heritage, this identity made him a target of the Nazi regime during World War II. Some of the leaves appear detached, which adds to the idea of impermanence and can allude to diaspora and his eventual extermination in Auschwitz in 1944. Editor: That context certainly enriches our understanding. Perhaps it’s the premonition that seeps through its inky shadows. In retrospect, it amplifies that sense of contained dread so powerfully present within it. Curator: Absolutely. It encourages a powerful dialogue about the intersection between art, identity, and historical context. Editor: An artwork that offers us a historical document but more intimately speaks to a human experience marked by tragedy and survival.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.