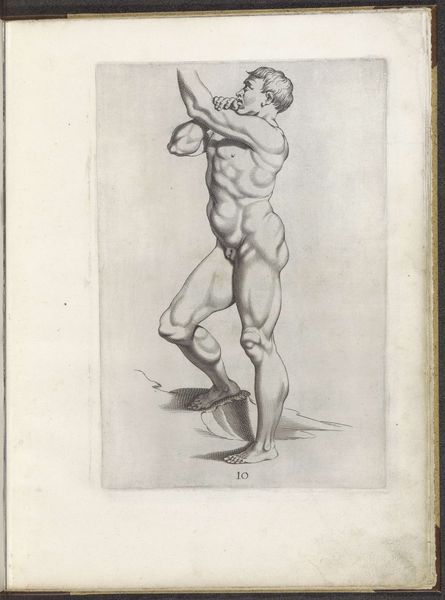

drawing, print, ink, engraving

#

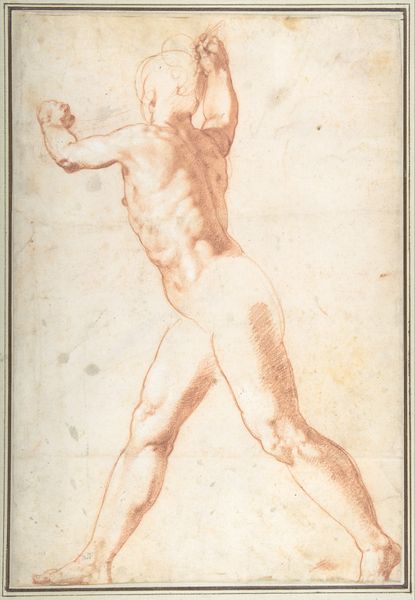

drawing

#

aged paper

#

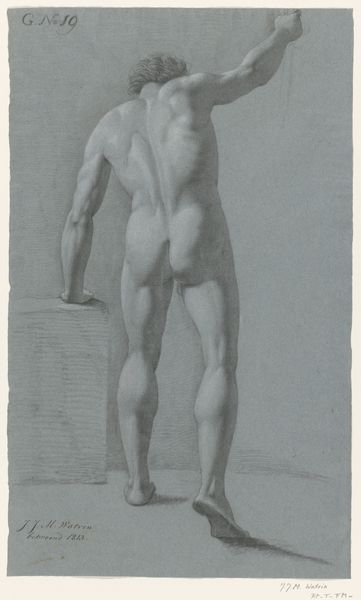

toned paper

#

light pencil work

# print

#

figuration

#

form

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

line

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

#

engraving

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

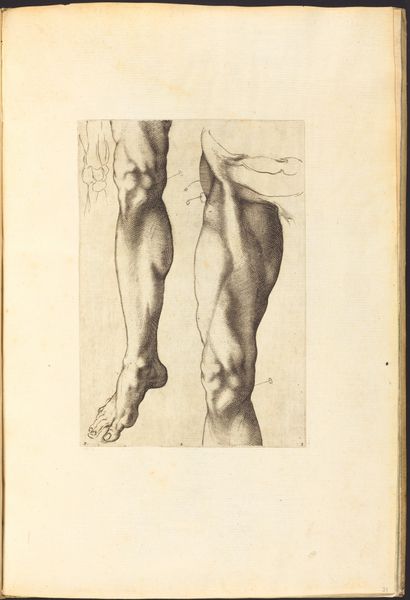

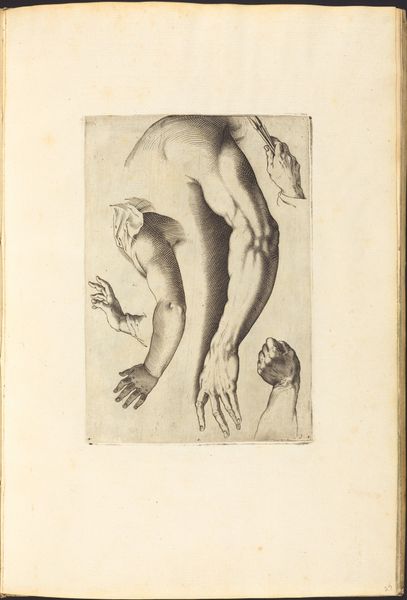

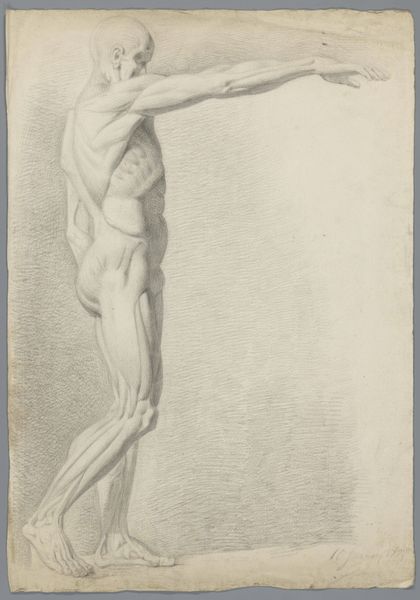

Editor: So, here we have a print, "Print from Drawing Book," dating from around 1610-1620, by Luca Ciamberlano. It’s primarily ink on paper – a detailed study of a leg, seemingly plucked from an anatomical textbook. I'm struck by the sheer... dryness of it, almost clinical, and yet, something about the lines is also beautiful. What do you make of it? Curator: Dry, you say? Hmm. I see a leg wrestling with the very idea of *leg-ness*. Look how Ciamberlano isolates it, stripping it of context, forcing us to confront its form, its muscle, its... purpose, wouldn’t you say? And those delicate pinpricks… almost acupuncture! It's Renaissance curiosity colliding with an artist’s analytical eye. Does that anatomical bent change how we might relate to it today, versus when it was created? Editor: Well, now it makes me think of Da Vinci’s anatomical drawings, or maybe a medical student's notes. But this feels different, less scientific and almost... performative? The leg isn't attached to a body, it's floating! Curator: Floating, exactly! It becomes a symbol, almost an ideal leg, no? What do we do with this *idealized detachment* though... Maybe this artistic exaggeration invites us to find new definitions? To move, perhaps? See, the piece lives when we start projecting and responding back to its original statement about "art" and "self". Editor: Projecting is a good word. Thinking about my own body in relation to it... So, initially, I saw dryness, but now it’s almost... engaging? Curator: Precisely! It's a conversation between lines and ideas, bodies and ideals – and us, darling, right now. Always about finding a new part of the exchange that lingers a while with us after the fact.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.