print, woodcut, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

pen sketch

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

line

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 65 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

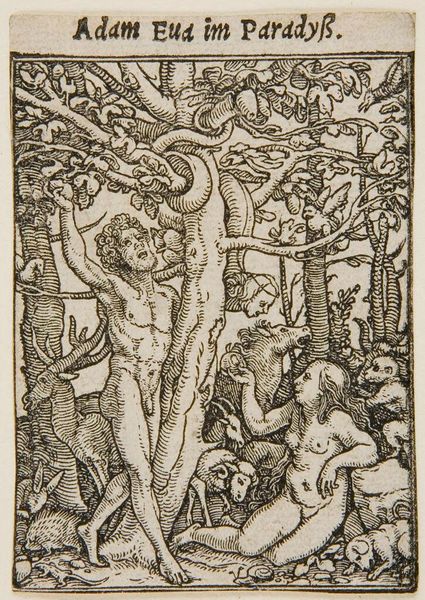

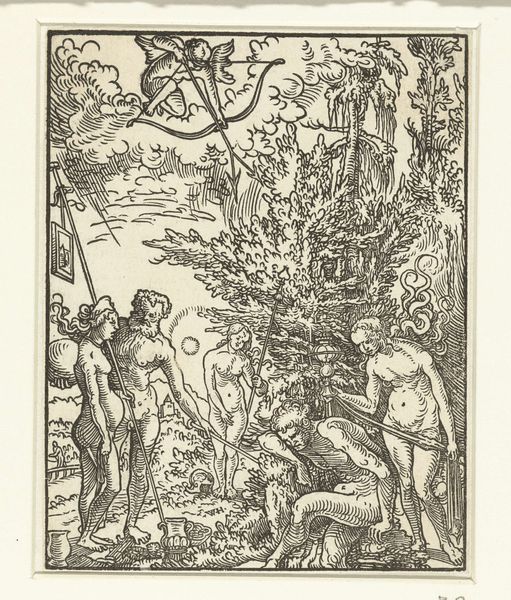

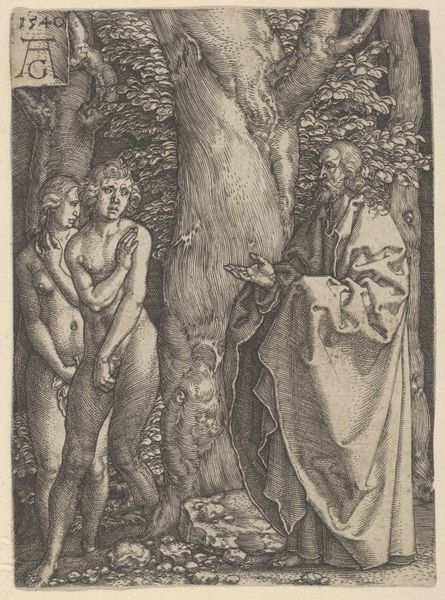

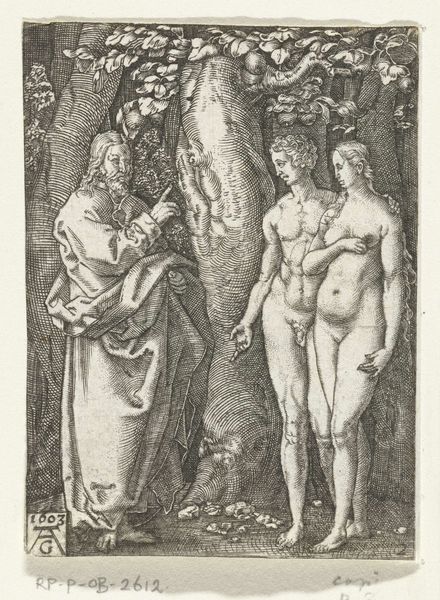

Curator: Look at this fascinating piece; it is called Zondeval, or The Fall of Man, created by Hans Holbein the Younger sometime between 1524 and 1538. It's a woodcut, part of a series exploring stories from the Old Testament, currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My immediate impression is one of unease. There’s a frenetic energy to the composition, a real sense of disruption communicated through the stark lines. The whole scene is dense, claustrophobic almost. Curator: Precisely. Holbein uses line to masterful effect, creating depth and texture. Notice how he populates the Garden with creatures – not the serene paradise one might expect, but a forest teeming with anxious-looking animals. The cultural memory here is about so much more than a simple error of judgment; there is the deep sense of disruption of an entire ecological order. Editor: And what about the figures of Adam and Eve? The image certainly diverges from traditional depictions of them. Their nudity feels exposed, vulnerable, a departure from classical idealism. The figures don't exist in isolation, which is to say that it reflects back on the broader visual and political context of Holbein's era. Curator: Indeed. They reflect a very human anguish and psychological reckoning, the consequence of the Fall laid bare on their very beings, echoing the moralizing trends popular during the Northern Renaissance. See how the serpent dominates the scene? It wraps the tree with almost sensual malevolence, becoming the focal point that precipitates action and consequence. Editor: The tree of knowledge then transforms into an almost violent spectacle, disrupting a sense of stability, while Adam and Eve appear to become separated not just from grace but each other as well. How much of this commentary speaks to the broader anxieties of the time, particularly about religious authority and moral decay? Curator: Absolutely, and there's more to unpack in relation to social structure and shifting cultural ideals. Holbein’s woodcut captures a moment laden with not just religious weight but cultural and psychological shifts as well. Editor: The brilliance lies, perhaps, in its capacity to speak volumes on cultural anxieties using such stark, graphic immediacy. A profound exploration, wouldn’t you say?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.