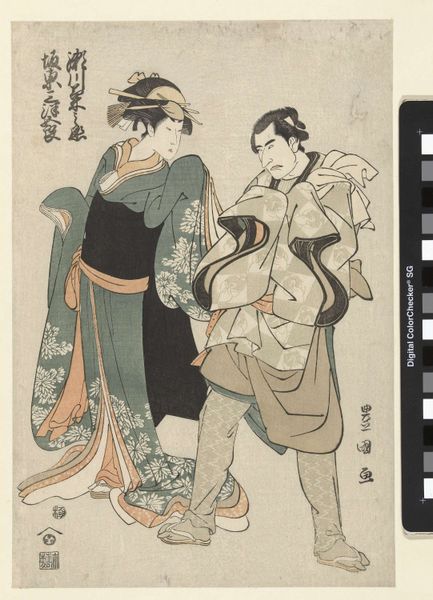

print, woodblock-print

#

portrait

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

woodblock-print

#

line

#

genre-painting

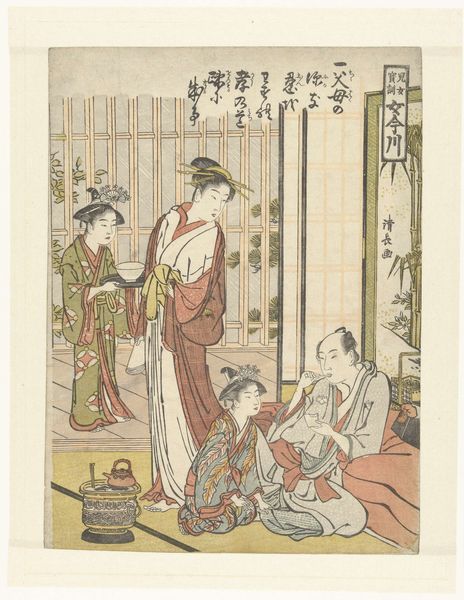

Dimensions: height 253 mm, width 187 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

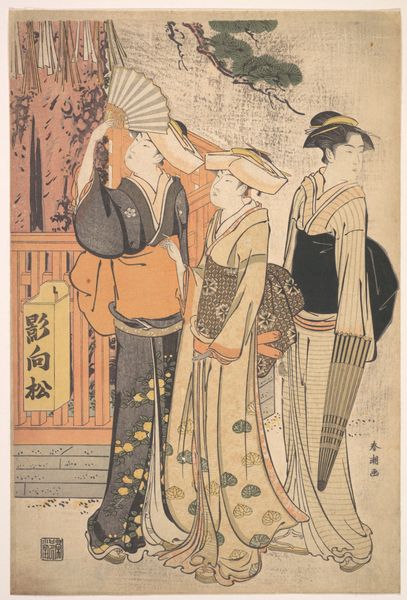

Curator: Here we have Torii Kiyonaga's woodblock print, "Avondboot te Tomigaoka," dating roughly from 1779 to 1783. It's part of the Rijksmuseum's collection. Editor: Immediately I see a dreamlike quality, almost a serene sadness. The figures seem suspended in a moment of quiet contemplation. Curator: It's fascinating to consider the ukiyo-e tradition, the "pictures of the floating world." The process of creating these prints involved a collaboration of artisans – the artist, the carver, the printer, and the publisher. The quality of the materials, like the paper and the inks, all affected the final piece, and the social system of consumption made these images available to a wide audience. Editor: Indeed, and beyond the materials, I am captivated by the emotional depth that Kiyonaga evokes. The figures are carefully positioned, aren't they? Note how they are arranged around this boat like elements in some kind of story or ritual. The bamboo fencing offers these beautiful vertical lines behind which they partially hide. I wonder what it could symbolize: perhaps secrets being kept? Curator: I think examining the labor involved is vital too. Each line had to be carefully carved, each color precisely applied. Mass production techniques in those days meant someone’s skilled labour made all these exist. Look how those costumes were represented as being made of rich fabrics; what might the subjects think when looking at themselves? Editor: Consider too how their hairstyles create a halo effect, an almost saintly quality. The figures, however idealized, echo across cultural time. It’s amazing what the image itself recalls – universal themes like love, loss, friendship and longing. These themes feel somehow emphasized here as if highlighted with light in ways we never knew. Curator: Right, thinking about labor highlights their elevated status. Even the act of viewing the boats would be a sign of wealth and freedom to watch how people consume things! Editor: Ultimately it’s about memory. The image is never truly static; instead, its story morphs in relation to how its audience imbues meaning from one era to another. Curator: So much to learn here when we examine it at Rijksmuseum closely. Thanks for sharing those observations with me. Editor: Thank you, too. A true pleasure when art evokes multiple levels of interpretation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.